For the past six months I’ve enjoyed sharing my impressions of various films featured in Criterion’s Eclipse Series of DVDs with our readers, each week choosing one title from the sets that have been released so far (except The First Films of Akira Kurosawa, which I reviewed as a whole, with capsule summaries of each film.) Now that I’ve sampled all 24 of these boxes, I’m glad to have the opportunity to pay some return visits to these amazing collections of “lost, forgotten or overshadowed classics,” this time in a more random order, basically choosing whatever title suits my interests at the moment. This week, I’ve chosen Tokyo Twilight, from Eclipse Series 3: Late Ozu.

This 1957 film falls right in sequence with where I’m at on my Criterion Reflections blog, where I’m nearly two years through a project of watching all the Criterion films in their chronological order of release. And with speculation about a Criterion Blu-ray re-issue of Ozu’s Tokyo Story that will either be confirmed or denied before this column publishes, it seems pretty timely to discuss one of Ozu’s follow-ups to that classic.

Tokyo Twilight lives up to its title in both narrative tone and cinematography as one of Ozu’s darkest and chilliest works. Set in the winter, the only one of his seasonally-themed films to take place during those months, Tokyo Twilight also marked the end of an era as Ozu’s final film shot in black & white. Most of its action takes place after sundown, in a variety of seedy bars and rough-edged hangouts; even the exterior images used to punctuate and transition between scenes feature very little that could be considered among the most aesthetically pleasing of Ozu’s celebrated “pillow shots.”

No tranquil waves, open fields, scenic mountains or lightly swaying tree limbs to be found here, though passing trains, power lines, bridges and smokestacks do make their obligatory appearances. Tokyo Twilight‘s overall atmosphere is one where nature seems distant, smothered beneath layers of business, industry and institutionalized education, where humans interact but essentially avoid each other, investing their energy in pointlessly distracting pastimes, propped up by polite but superficial and dishonest mannerisms, until uncomfortable and overdue personal encounters are forced by sheer weight of circumstance.

The story revolves around a pair of crises that develop in the family life of Sugiyama, a respectable banking executive who’s raised two daughters to young adulthood as a single parent. One of the crises, involving his oldest daughter Takako and her daughter Michiko, opens the film and serves as the framework for everything that follows. Her arranged marriage to Numata, a hard-drinking and easily angered academic, has turned abusive and she can’t take it anymore, so she abruptly decides to move back into her father’s house.

The second crisis concerns his youngest daughter Akiko, a child doted on by her father but who’s adopted Western mannerisms and drifted off into aimless bad-girl behavior, hanging out in bars and mahjong parlors late into the night, verging closer to open defiance and disrespect of her father and society’s expectations for young women. True to form, we soon begin picking up clues that her recklessness has gotten her into trouble with an unintended pregnancy, a shiftless and evasive boyfriend and no practical options to turn to for support.

Akiko’s sullen rebellion and deep-seated mistrust of the adults around her may not have won her much sympathy with some in Ozu’s audience – Tokyo Twilight was one of his least commercially successful films in its original release – but a case can be made that she had legitimate reasons for feeling as she did. Despite the apparent indulgence of her father, she senses that something’s been amiss in her relationship with him and the rest of her family for many years.

Now coming of age, and with a lot on her mind, Akiko discovers that the family history passed down to explain her mother’s absence was a fraud, aimed more at preserving a deluded sense of social propriety than in helping a child understand the decisions of the adults she naturally depended on.

As a narrative with overtones of melodrama or even soap opera, Tokyo Twilight works to devastating effect in demonstrating the long-term destructive powers of well-intentioned and carefully defended lies that too often lurk behind the methods parents and families use to raise children and avoid scandal. But as is the case with other Ozu films, the points he makes extend well beyond the purely domestic sphere, into larger cultural realms involving our political, spiritual and economic lives. Though Ozu himself famously focused his attention on the contemporary Japanese milieu in which he lived, his depths of insight and penetrating examination of the human predicament allows his films to easily transcend the time and place of their setting.

Admirers of Ozu’s unique approach to film-making will find plenty of reasons to mark Tokyo Twilight as one of his most distinctive works due to his willingness to explore themes more visceral and provocative than his usual motifs of forestalled happiness and patient longsuffering. As I’ve mentioned before, the typical route into Ozu’s works begins with the popular “Noriko” trilogy (Late Spring, Early Summer and Tokyo Story) in which the same actress, Setsuko Hara, plays three different characters, each named Noriko, all daughters to a father played by the ever-amiable and sympathetic Chishu Ryu. Tokyo Twilight reunites the pair, but changes the dynamics a bit, along with the obvious difference in the female protagonist’s name.

In the Noriko films, Setsuko Hara uses her amazingly subtle powers of expression to win the audience’s affection as the epitome of virtuous self-effacement and dignified endurance of potentially crushing disappointments. Here, she allows her disappointment to show more openly, in the form of resentment or restrained confrontation. Furthermore, she’s an accomplice to the repressive mechanics employed to manipulate younger women.

Perhaps this casting decision was made in response to the fact that Hara was indeed aging a bit here, no longer able to plausibly come across as the young unmarried daughter (even in Early Summer, from 1951, she was portrayed as being a bit overdue for securing her husband.) But it’s fascinating in any case to see a different side of this remarkably talented and charismatic actress. She would only make one more film with Ozu before retiring abruptly in 1963, still at the height of her massive popularity in Japan.

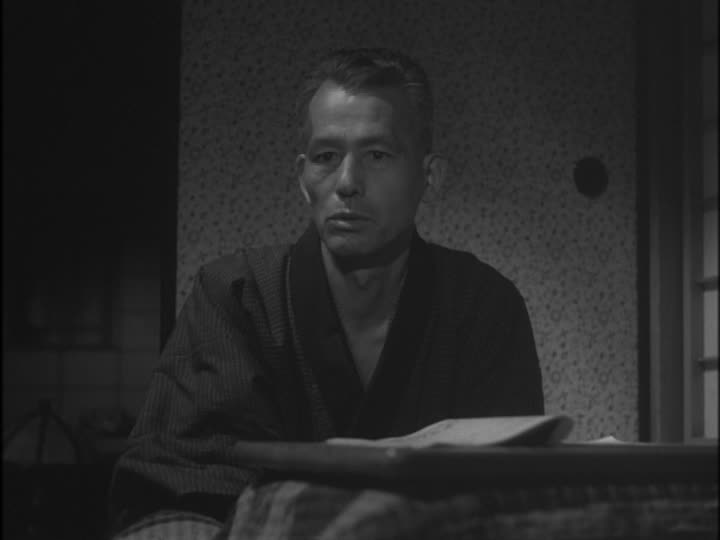

The young actress who plays Akiko, Ineko Arima, also stands out for her ability to capture the sense of blankness and futility that settles in on a young person who’s coming to realize the deception that lies behind the surface of what she’s been taught to trust and take for granted.

This clip provides a sample of her performance, remarkably understated when it could have easily and legitimately been ramped up for dramatic effect – and likely would have been in the hands of even very talented directors. I recommend it be watched only by those who’ve seen the movie (as a refresher) or for anyone who sincerely doesn’t mind seeing a highly pivotal exchange without benefit of all the build-up that makes it so effective.

For those of us who are parents, at whatever stage of that process, the scene provides a sobering reminder of how the convenient lies and pat answers we sometimes peddle to the children we raise can sow seeds of anger and heartbreak that come to bitter fruition many years later.

The gloom and shadows of Tokyo Twilight need not obscure us to truths we need to grapple with; on the contrary, by focusing our gaze and squinting through the darkness, we just may perceive important things we otherwise might have missed.

![Bergman Island (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/bergman-island-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/this-is-not-a-burial-its-a-resurrection-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![Lars von Trier's Europe Trilogy (The Criterion Collection) [The Element of Crime/Epidemic/Europa] [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/lars-von-triers-europe-trilogy-the-criterion-collection-the-element-of-400x496.jpg)

![Imitation of Life (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/imitation-of-life-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (The Criterion Collection) [4K UHD]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/the-adventures-of-baron-munchausen-the-criterion-collection-4k-uhd-400x496.jpg)

![Cooley High [Criterion Collection] [Blu-ray] [1975]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/cooley-high-criterion-collection-blu-ray-1975-400x496.jpg)

1 comment