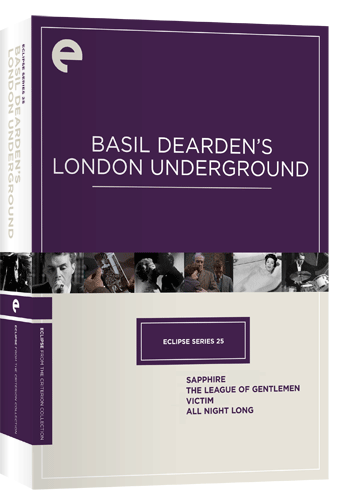

There are a few reasons that I could plausibly cite for choosing Victim, from Eclipse Series 25: Basil Dearden’s London Underground, for this week’s focus in my Journey through the Eclipse Series. For starters, Ryan, James and Travis recently discussed Gus Van Sant’s Mala Noche on the podcast, and a comparison between the two films could serve as the basis of an interesting conversation on how the handling of gay themes in cinema evolved over the course of 25 years. But I haven’t seen Mala Noche yet, so I’m not the guy to facilitate that discussion. I could also refer to the previous podcast episode on The Night Porter, since Dirk Bogarde starred in both that film and the one I’m about to review, but that’s not why either. And with a bit of creative license on the part of my readers, I don’t think it would be too much of a stretch to draw parallels between Victim‘s portrayal of the persecution endured by British homosexuals in the 1960s with some of the conservative political attacks being leveled against women seeking insurance coverage for contraception and other reproductive health issues that are occurring in the USA these days. Government-sanctioned imposition of morality on private personal affairs has led to a lot of needless suffering over the years, and sometimes a powerfully wrought drama can bring about a necessary change of perception in the minds of those otherwise susceptible to the demagoguery of fear and prejudice that seeks to justify such laws.

But the real reason that Victim is being reviewed this week is simply that it falls into the timeline of films I’m watching for my Criterion Reflections project, as it was released between Alain Resnais’ Last Year at Marienbad (which I wrote up a few days ago) and Jean-Luc Godard’s A Woman is a Woman (review to be posted soon.) Though it’s indisputably outweighed by those two films in terms of artistic innovation and the lasting reputations of their respective directors, I can argue that Victim had more profound real world consequences, in that the debate it helped stir eventually led to the repeal of Victorian-era laws passed in the late 19th Century that sent many men to prison terms of up to ten years simply for the “crime” of having sexual relationships with other men. The absurd extremity of these laws created a lucrative opportunity to intimidate and extort money or other favors from culpable men, once they knew that someone had the goods on them – photographs, letters, former partners ready to testify. Lives were being ruined for no justifiable reason, and something had to change. Much like Dearden’s earlier film Sapphire, which dealt with the reality of increasing ethnic diversity (and the racist backlash it generated) in England’s green and pleasant land, Victim marked a genuine breakthrough in forthrightly handling subject matter that was on many people’s minds but had yet to make it onto the surface of the mirror that cinema holds in front of society.

Judging from the films included in this Eclipse set, one might get the impression that Basil Dearden was a fearless provocateur, always on the lookout for some boundary-pushing project to stir up controversy or capitalize on contemporary political debates. While he deserves credit for his willingness to take on these taboo subjects, a closer look at his filmography shows that he was really just a busy journeyman director who took on a wide variety of genres, including two apparently forgettable films that he shot over a few months in between The League of Gentlemen (1960) and Victim (1961.) Due to that fast pace and crank ’em out production deadlines, Victim isn’t going to amaze us so much with its visuals or unconventional approach to story telling. As a film, it feels quite a bit like a well-crafted television show much of the time, with a lot of medium shots of characters in dialog, using tense facial expressions and reaction shots to convey the drama of pressures they’re feeling as their private lives and inner desires subject them to the risks of blackmail on the one hand and exposure leading to disgrace and imprisonment on the other. This video clip, which includes Victim‘s original theatrical trailer and a collection of posters and movie stills used to promote the film, provides excellent context that helps us get a feel for the cultural environment that the film was first introduced to:

The obvious avoidance of actually saying what the central problem consisted of in Victim is both fascinating and appallingly sad in its exposure of the deeply rooted homophobia that was just beginning to be questioned and rebutted in Great Britain at the time. Such alarmist, official sounding, hyper-dramatic intonations… As evasive and indirect as the script for that trailer was, at least the narrator spared us the cliché about “the love that dare not speak its name.”

Given the acute sensitivities of its era, and in plain recognition of the fact that the film makers were advocating for a change to the laws (and were thus open to charges of actively promoting immorality and corruption,) construction of a narrative that served to persuade its audience presented some difficulties. Dearden and crew had to work carefully to develop sympathetic characters whose behavior was typically portrayed and regarded as deviant, unnatural and discomforting to the majority of viewers. Victim received an X rating, according to the standards of the day, even though there were no displays of same-sex affection (though a few full contact hetero kisses were thrown in, perhaps as a gesture of reassurance to squirmier members of the audience) and nothing more erotically descriptive than pithy phrases about how “the invert is part of nature,” “being a born odd-man-out” and “finding love in the only way I can.” Still, the word “homosexual” is uttered on a few occasions, and the word QUEER is painted in big white letters on a garage door. Shield the eyes and ears of the children!

So beside its courage in broaching a topic that most in the entertainment industry preferred to keep underground, Victim can also be credited for crafting a tale that is genuinely involving, full of twists and turns that keep us curious to see what happens next even as we wrestle with whatever vestiges of anti-gay bigotry disrupt our ability to empathize with the characters’ dilemmas. We start by tracking a distraught young man, Jack “Boy” Barrett (pictured above, walking past a theater where the musical Oliver! is playing, destined to become an Oscar-winning film late in Carol Reed’s career.) Barrett senses the police on his trail and he seeks the assistance of Melville Farr, a barrister of sterling reputation who’s recently become more than just a friend. Farr is highly conscious of the damage to his career that Barrett could inflict if he were to make details of their relationship public. This despite the fact that nothing criminal has occurred between them, even though the desire is felt acutely by both men. Farr rebuffs Barrett’s desperate phone calls, convinced that the young man he’d become so fond of has now turned to extortion to avenge the end of their affair.

Barrister Farr also happens to be married to about as comely a specimen of fine English womanhood as any man could wish for. His wife Laura puts in hours as a social worker helping “difficult children” and clearly loves her husband, though she knows of his previous romantic involvement with another young man in the years before they were married. Farr is a classic closet case, seeking to sublimate his desires in a respectable marriage that’s based on a sincere emotional commitment but remains stubbornly less than satisfying for them both.

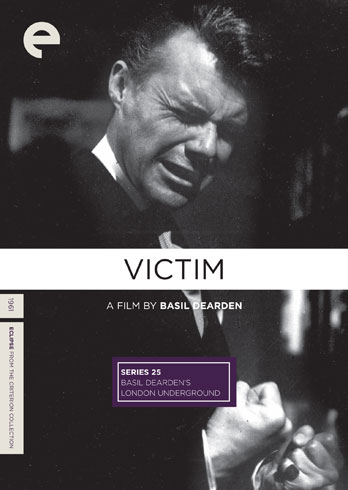

As the man at the center of the story, Dirk Bogarde turns in a powerful and compelling performance, made all the more profound as one ponders that he was a closeted gay man himself who took on this role against the matinée idol type that he’d cultivated in his previous film and television work. Bogarde makes himself emotionally vulnerable here, even though the script takes a few precautions to indicate that he never crossed the line into buggery, only that he “wanted” to. That too-apparent hint of desire, and a photograph that could be interpreted negatively by a gossiping mob mentality, is enough to toss his prospects for professional advancement out the window, should the slim evidence become public knowledge. Knowing how closely Victim‘s plot and Farr’s peril resembled his own real-life situation must have given Bogarde’s performance an extra spark, and one can definitely sense a heightened strain of anxiety coming through, marked by more genuineness than mere acting usually conveys.

Beyond Bogarde’s magnetic screen presence, Victim also stands out as a showcase for a fine cast of colorful British character actors, a few of whom are familiar from previous films in this set, as well as some evocative London street scenes. Above, Mickey and P.H. stroll past Nelson’s Column in Trafalgar Square as they plot their next move in delivering their blackmail to the marks they monitor at a nearby pub.

Harold Doe, a meek bookseller and lifelong bachelor, mourns the loss of his young protegé Boy Barrett while the sinister Miss Benham glowers at him coldly upon hearing the sad news.

The barbed repartee down at the Saloon injects a few laughs and some pathos into the story even as it advances the plot through its convoluted entanglements of melancholy souls.

And even though Melville and Laura find their marriage severely tested by the turmoil and uncertainty that’s been thrust upon them, straight members in the audience are spared from having to watch them break up entirely due to his sexual orientation or any other irreconcilable differences. Such implications were clearly too heavy and potentially disturbing to deal with at the time, and they still present difficulties for many viewers today. As Victim draws to its conclusion, one simple message emerges from amidst all the other moral and social complexities that it stirs up: fearful prejudice, bitter contempt and legalistic persecution that are directed toward any form of love between consenting adults makes victims of us all.

![Bergman Island (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/bergman-island-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/this-is-not-a-burial-its-a-resurrection-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![Lars von Trier's Europe Trilogy (The Criterion Collection) [The Element of Crime/Epidemic/Europa] [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/lars-von-triers-europe-trilogy-the-criterion-collection-the-element-of-400x496.jpg)

![Imitation of Life (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/imitation-of-life-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (The Criterion Collection) [4K UHD]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/the-adventures-of-baron-munchausen-the-criterion-collection-4k-uhd-400x496.jpg)

![Cooley High [Criterion Collection] [Blu-ray] [1975]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/cooley-high-criterion-collection-blu-ray-1975-400x496.jpg)