It’s a silly story, only possible with music.

After spending last weekend immersed in the horrors of trench warfare, World War I style, via Raymond Bernard’s Wooden Crosses, I’m in the mood for something light and frivolous – how about a romantic comedy, a musical one at that? Sure – Criterion’s Eclipse series has got just the thing for me, in Eclipse Series 8: Lubitsch Musicals. But which one of the four best fits the occasion? Well, it’s the first weekend of June, that time of year when blissful young couples traditionally get married, a custom going back to ancient Roman times when Juno was paid special homage as the goddess of marriage. Of course, June weddings also have the practical advantage of ensuring that if the bride gets pregnant on the honeymoon, she won’t be ready to give birth until after the harvest time, and the baby should be born before the spring planting season has begun. That’s the angle that our agrarian ancestors came up with, and the ritual (with all of its embedded patriarchal assumptions) lives on, to some extent anyway.

Perhaps it’s that sense of marriage as a trap, when the arrangements are made for all the wrong reasons, that gives some potential spouses a case of the cold feet when it comes time to take that final stroll down the aisle. The archetype of the “runaway bride” goes back well before the uproar stirred up by Jennifer Wilbanks in 2005, when she vanished a few days before her wedding day, drawing national media attention and even suspicions of murder toward her fiance, before she was tracked down and offered a blatantly false and racist explanation for her sudden disappearance. Some may also remember the mediocre (at best) Julia Roberts film Runaway Bride from 1999, especially those of us who were dragged there reluctantly by our own spouses/dates/significant others (sorry if I stirred up any unwelcome memories for our readers with the citation.) But that cinematic trope goes back considerably further than the late 90s, all the way back to the very early days of the sound era, maybe even further – but we’ll stop there.

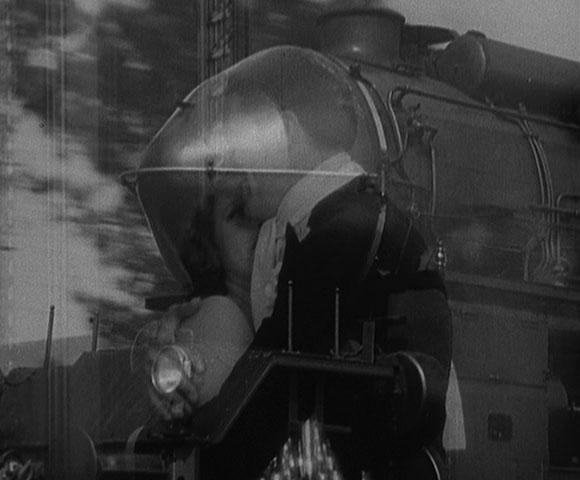

Monte Carlo (1930) tells the story of Countess Helene Mara, an impulsive young thing who somehow finds herself about to be hitched to a blithering idiot who also happens to be an extremely wealthy Austrian aristocrat, Duke Otto von Liebenheim. The picture opens as we see all the preparations coming to fruition in a palatial setting, seemingly every girl’s dream wedding about to unfold. But the weather turns bad, the wedding dress doesn’t fit, and Helene suddenly realizes that her destiny won’t be found by marrying the pompous fool to whom she’s been betrothed. Instead, she’ll need to make a break for it, setting out “Beyond the Blue Horizon” to discover what life has in store:

Even if you only watch the first two and a half minutes of that clip, you’ll see some stuff that was quite innovative and influential in its time. Monte Carlo was released just several months after Lubitsch’s highly successful, Oscar-winning The Love Parade (also part of this set), the first full-fledged Hollywood musical to weave songs directly into the narrative. These early entries into such a venerable genre began establishing its vocabulary, taking the musical comedy format in directions that couldn’t be replicated on stage. Incorporation of train sounds (wheels, engine, whistle) into the propulsive rhythm track, outdoor location shots, the use of waving field hands as a visual stand-in for the chorus – this was all new stuff that really took the public by storm at the time. In a sense, watching a film like Monte Carlo is like being present at the creation of a major new development in cinema. A nice bonus is the fact that these oldies also pack a fair amount of entertainment value, loaded with saucy innuendos, vintage Art Deco design touches and sharp-but-subtle jabs at provincial middle-class moralism.

Either because or in spite of Lubitsch’s European background, his ability to playfully subvert American prudishness surrounding sexuality and conventional domestic arrangements won him huge audiences, and he went on to become one of the most prominent directors of Hollywood’s Golden Age. A pair of his later films, Trouble in Paradise and Heaven Can Wait, made it into the Criterion Collection and probably provide a better first experience of the Lubitsch touch for today’s viewers, since they require less front-end adjustment on our part to the quaint styling of early talkies. Still, the Lubitsch Musicals set features films created just before the infamous Production Code went into effect, as Hollywood took it upon themselves to impose their own brand of censorship in order to avoid threatened legal action as the blue-nose brigades shifted their attention from Prohibition (just coming to an end) to stamping out wanton sinfulness in the cinema. It’s interesting to compare American films made before and after 1934, when there’s a noticeable drop-off in the degree of candor and sophistication dealing with sensitive subject matter. Monte Carlo features several scenes where Helene signals to the audience, through body language or sensual moans, the afterglow of a sexually satisfied woman, all played to comedic effect of course, and never venturing into any territory we’d consider explicit by today’s standards. But that kind of carrying on wouldn’t have gotten past the Hays Office by the mid-30s!

Besides Monte Carlo‘s historic value, it serves as a wonderful showcase for the fetching Jeanette MacDonald, one of the most popular screen stars of the 1930s. I admit, upon first hearing her hit those high soprano notes in that constrained vocal style, I wasn’t an instant fan. But she’s a delightful performer, with a killer smile, bright eyes and a willingness to breezily strip down to her negligee for the sake of a laugh. Give the tunes half a chance and I bet your toes will be tapping along to “Always in All Ways” before too long. Her “good sport” attitude, of a very pretty female star who’s willing to take her comedy into territory more risque than expected, is reminiscent of the impression Cameron Diaz left on me in There’s Something About Mary back in the 90s.

MacDonald’s star power shines a bit more brightly here than in the set’s other films since she has no compelling rival for screen time, which ends up hampering Monte Carlo‘s overall effect. I get the sense that Lubitsch was doing the best he could, working with the hand he was dealt in shooting this picture. After Countess Helene ditches Duke Otto and runs off to hit the casino, she’s spied by another upper-class idler, Count Rudolph Farriere, who concocts an absurd scheme to pose as her hair-dresser and eventual manservant, moving on from there to even greater intimacies. He’s played by British actor Jack Buchanan, whose credibility as a male romantic lead must have been established on the English stage some years earlier, since he seems well past his prime here. Compared to the magnetic wit and charisma of Maurice Chevalier, who co-starred with MacDonald before and after Monte Carlo but was unavailable for this picture, Buchanan’s nasally voice, gangly physique and simpering mannerisms left me unwilling to accept that the free-spirited Helene would really fall as hard for Rudolph as appearances would have us believe. Then again, the hottest emotional exchange between the two of them occurs when she’s convinced that Rudolph has just broken the bank with his gambling skills – when he pulls out a wad of 200,000 francs, she rewards him with electric eye contact and a big kiss. Now that I can believe!

Of course, he does compare favorably with Duke Otto, and since there are no other eligible bachelors with a bankroll sufficient to fund the extravagance she’s grown used to, I suppose we can’t fault Helene too much for making the choice she did. I doubt that I’m spoiling anything by telling you that Helene and Rudolph wind up together at the end of the picture, back on that train, but heading in the opposite direction. No mention of them getting married though, which was a relief. It leaves open the possibility that Helene might pull her runaway bride trick one more time and venture back out on her own to find herself a man truly worthy of her vivacious charms!

![Bergman Island (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/bergman-island-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/this-is-not-a-burial-its-a-resurrection-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![Lars von Trier's Europe Trilogy (The Criterion Collection) [The Element of Crime/Epidemic/Europa] [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/lars-von-triers-europe-trilogy-the-criterion-collection-the-element-of-400x496.jpg)

![Imitation of Life (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/imitation-of-life-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (The Criterion Collection) [4K UHD]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/the-adventures-of-baron-munchausen-the-criterion-collection-4k-uhd-400x496.jpg)

![Cooley High [Criterion Collection] [Blu-ray] [1975]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/cooley-high-criterion-collection-blu-ray-1975-400x496.jpg)

3 comments