Maybe it’s only fitting that family commitments (and, I’ll admit, the return of nice weather to the area where I live) kept me busy enough to delay the writing of this week’s Eclipse Series column. After all, the themes of the films I’ve been watching lately have a lot to do with the disillusionment that settles upon young children when they discover the misguided priorities of their parents. And even though my own kids are well past the ages of Antoine Doinel in The 400 Blows and the even younger Keiji and Ryoichi in I Was Born, But…, I’m still conscious of the example I set and don’t want to do anything that will only add to their cynicism regarding the world that the adults have so badly prepared for them.

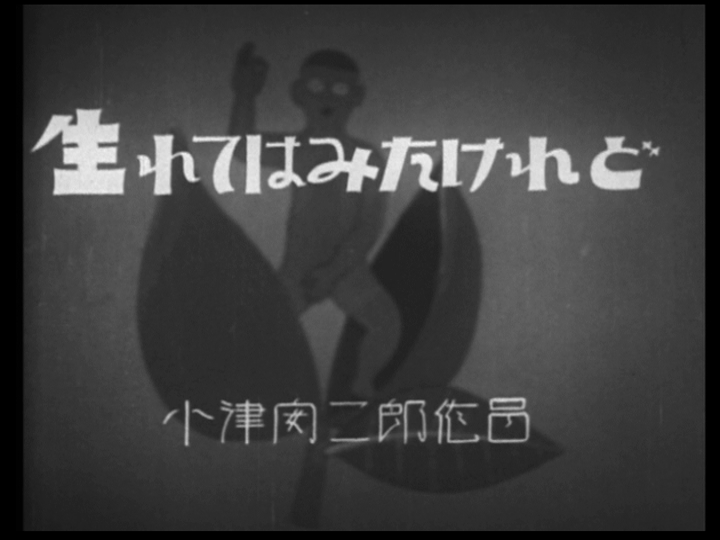

Now you may be wondering what the French Nouvelle Vague breakthrough The 400 Blows has in common with an old Japanese silent comedy from the 1930s, beside the fact that they’re both focused on children, and what leads me to pair them up to lead off this column? It’s another example of the interesting confluences that develop from time to time as I wind my way chronologically through the Criterion Collection on my Criterion Reflections blog. Last week I spent a lot of time watching and pondering Truffaut’s debut, and when I was done with that, this early family comedy from Yasujiro Ozu was up next in my queue. But that has more to do with the next Reflections blog entry, Ozu’s 1959 Technicolor comedy, Good Morning, which is a reworking of the basic story line that he first put forward in I Was Born, But… It’s from Eclipse Series 10: Silent Ozu.

Now I’ve seen Good Morning, though it’s been a few years, but I’m not going to say anything here about that film; I’ll save it for my other blog. I Was Born, But… is a superb and important film in its own right, one that some reviewers consider superior to the remake issued 27 years later. Like The 400 Blows, it marks a major step forward for a director destined to leave a big imprint on the history of cinema, even though Ozu was considerably further along in his career than was Truffaut. It’s listed as his 24th film, which sounds like a lot, but another way of looking at it was that he’d been a director for a little over five years, with 30 more years of film making ahead of him, so it still ranks as an early work, and the one in which his classic style begins to emerge in its maturity.

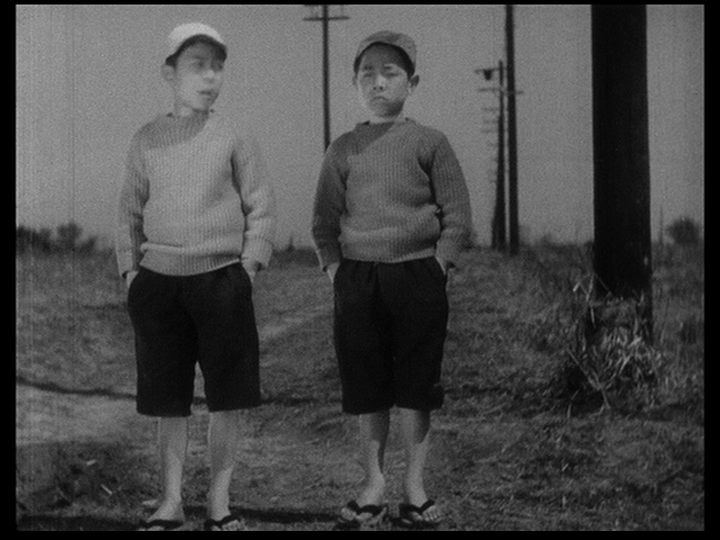

The film opens with a comic but also symbolic image of a tire spinning in the mud, unable to get out of the rut its fallen into. The wheel is attached to a truck that’s being used to move a family’s belongings into a new home and neighborhood. The father, Kennosuke, is relocating his household in order to be closer to his employer, presumably with the intention of demonstrating his worth and loyalty to the company. Even though he’s probably convinced that he’s doing it for the good of his family, his sons Keiji and Ryoichi quickly develop contrary opinions of their own. As the new kids in that rough-hewn, still developing suburb of Tokyo, they have to settle in and figure out where they rank in the social pecking order. And any kid who’s ever had to go through that experience knows that it’s rarely an easy or comfortable process.

Ozu spends a lot of time in that juvenile milieu, incorporating a lot more physical comedy and childhood pratfalls than viewers of only his later films might expect. It makes for a fun and lively first half of the film as we see the boys jostling for acceptance by proving their fearlessness and figuring out ways to one up the bullies.

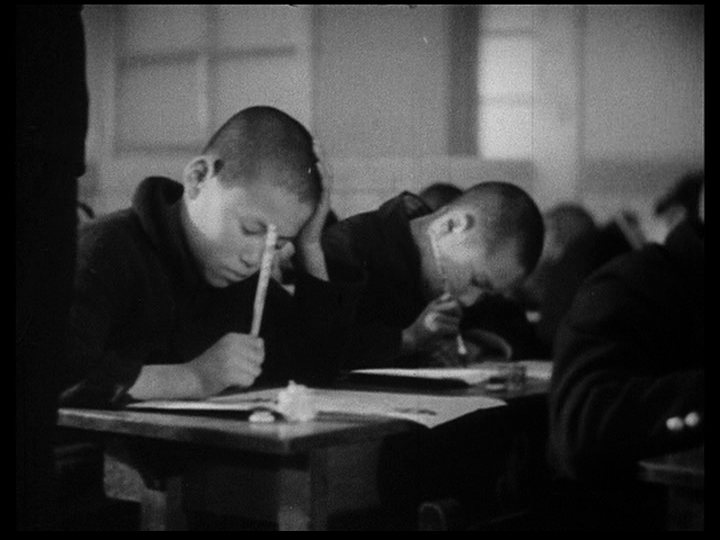

And then there’s the problem of school – which brings up another point in common with The 400 Blows, in that both films feature boys who just decide that going to class just ain’t worth the hassles that come with it. Comparing the two side by side, I think that Antoine Doinel has the better time of it playing hooky, though Keiji and Ryoichi get off lighter when it comes to the inevitable consequences.

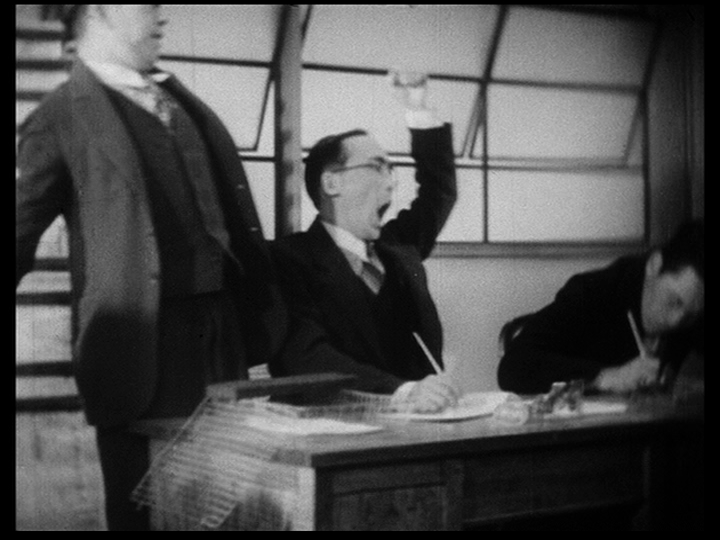

Ozu’s satirical edge begins to show through as he draws up the parallels between the schoolboys’ drudgery laboring over their pointless calligraphy exercises and the long rows of yawning paper-pushing drones that their fathers have become. Chief among them is Kennosuke, whose lowly and dependent status prods him to debase himself in a socially acceptable way…

…. by too-obviously currying the favor of his boss, and what’s even more appalling – to his sons at least – by sucking up to his employer’s kid, one of those aforementioned bullies who’s been giving Keiji and Ryoichi so much grief.

Their dad’s clumsy meddling into the important matter of neighborhood hierarchy amongst the boys threatens to undo the fragile progress that Keiji and Ryoichi have made, injecting some serious notes of strain into the family relationships even as they provoke laughter and nods of familiarity from the audiennce.

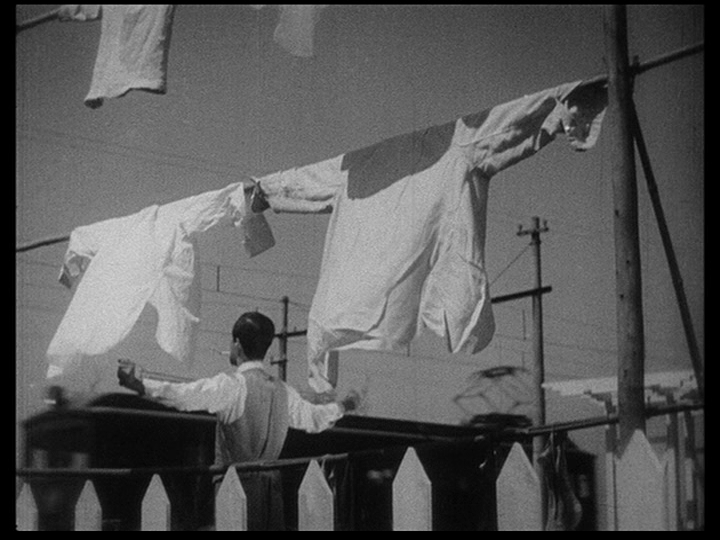

Ozu also treats us to a few early examples of his trademark pillow shots, though they’re not quite as ostentatiously presented here as they would become in later films. The second one here packs in two of his favored images, clothes on the line and trains, along with Dad combining his morning exercise with a smoking break.

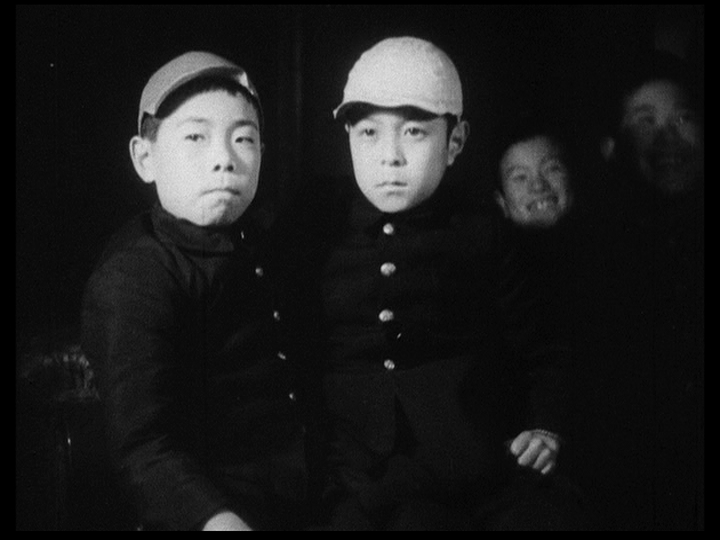

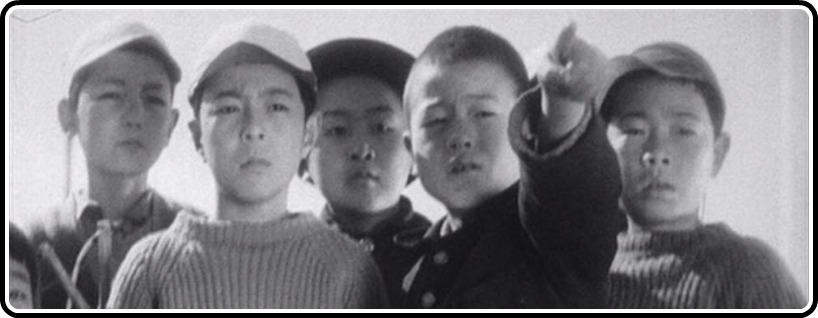

Ozu also shows his deftness at directing child actors, positioning the two boys in a variety of Tweedledum and Tweedledee poses that never fail to generate a smile as they mug so amusingly for the camera…

… and also demonstrate the harsher side of early life experience, as they experiment with smoking, throw some epic tantrums and push their father to the point where he finally resorts to spanking.

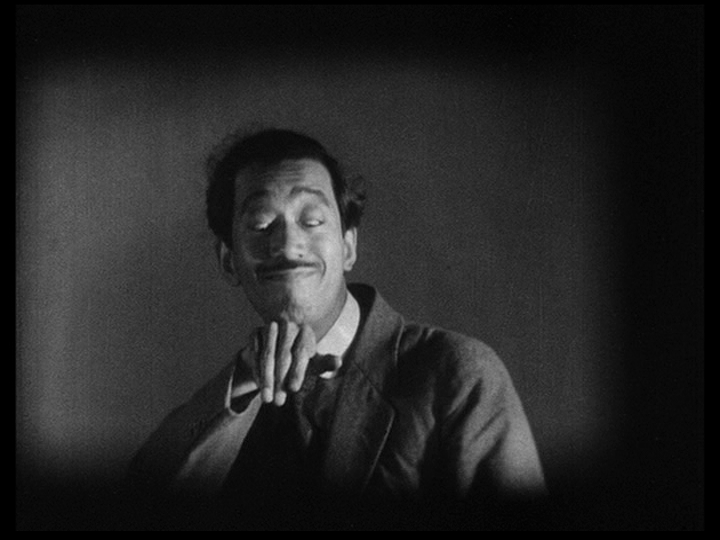

And who can blame the boys, as they witness one degrading demonstration after another by their old man, who exposes the incongruity between his stern, disciplinarian demeanor at home and the pathetic buffoonery that he engages in to win a few laughs among his professional colleagues? Keiji and Ryoichi have seen enough – they want nothing to do with this loser of a father! But they’re willing to give him one last chance, if he’s willing to man up and turn the tables on his boss (and by extension, undo the damage he’s done to their own efforts to climb up the ranks with their peers.)

After hearing their father’s rationale for his subservient role in the company, that his salary allows them to eat, the boys decide to go on a hunger strike to prove their point, that they don’t need their dad to stoop so low for their benefit. But a night of growling tummies and Mother’s offer of sweet rice balls the following morning erode their fierce determination, and the lesson learned, so often repeated throughout the rest of Ozu’s career, in ever more subtle and sophisticated ways, is that we all have to make concessions to the immutable demands of our roles and relationships in life. It’s not always easy or enjoyable to endure, and what’s expected of us certainly isn’t fair. None of us asked to be born, but… we were, and now we have to deal with it. At least we have the movies to help us make some sense of the whole thing.

![Bergman Island (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/bergman-island-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/this-is-not-a-burial-its-a-resurrection-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![Lars von Trier's Europe Trilogy (The Criterion Collection) [The Element of Crime/Epidemic/Europa] [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/lars-von-triers-europe-trilogy-the-criterion-collection-the-element-of-400x496.jpg)

![Imitation of Life (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/imitation-of-life-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (The Criterion Collection) [4K UHD]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/the-adventures-of-baron-munchausen-the-criterion-collection-4k-uhd-400x496.jpg)

![Cooley High [Criterion Collection] [Blu-ray] [1975]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/cooley-high-criterion-collection-blu-ray-1975-400x496.jpg)

1 comment