If Sunnyside (1919) was a difficult creative experience for Charlie Chaplin, and by all accounts it was, we should all be so lucky to produce such works under such creative blocks. Chaplin began production on the film very quickly after marrying 16-year-old actress Mildred Harris, who believed herself pregnant by the filmmaker. He would come to regret the decision almost immediately, finding her intellectually inferior and later accusing her of infidelity. To make matters worse, their eventual child, born a month after Sunnyside‘s release and almost nine months exactly following their marriage (though the question of whether Harris was pregnant prior to matrimony is unclear), died only three days after his birth. In the midst of these unhappy circumstances, Chaplin had barely a thread of an idea for a short film – the Tramp works on a farm – but, fortunately, a patient studio to bear him out.

Personal tragedies aside, Chaplin’s days at First National seem like a bit of a dream. His previous deal at Mutual afforded him total artistic freedom, but the pace that was demanded of him – twelve two-reelers in eighteen months – resulted in a freedom he could not always afford to explore. At First National, however, he was required only to produce eight films, which were eventually released over the course of five years. And though the intention was for them all to be two-reelers in the model of his Mutual shorts (typically running 20-24 minutes), an overview of his work at First National shows he pretty much did as he pleased, frequently producing films in the 30-40 minute range, one 7-minute film, and two features.

Sunnyside is a spare film, even for its 30-minute running time – the first half is composed entirely of loosely-connected gags, and even the “plot” ends up not being much of a plot at all – but Chaplin draws from its trappings endless amusements, due, I’m sure, in no small part to the film’s unusual production. Chaplin brought his cast and crew to a California ranch, hiring needed cowhands and appropriate animals, but couldn’t think of anything to do with them. This lasted for three months, during which he temporarily abandoned the project until he forced himself into a three-week comedic sprint, and quickly finished the film thereafter.

The result does seem like the product of a tapped nerve, a sudden burst of inspiration without a specific regard to structure, theme, or even story. Right away, he seeks to quickly dispense with formalities with his own introduction:

And he does take on certain formalist concerns, making sure we know what kind of movie this will be (or could be) by bringing in elements that are just slightly out-of-place to introduce the possibility of the surreal and fantastic. Here, as he prepares breakfast, he takes an innovative approach to getting cream for the coffee (with due respect to its provider):

As much as Buster Keaton gets tagged as “The Great Stone Face,” part of Chaplin’s skill as a comedic performer was in underplaying moments such as these. By just giving a quick, unembellished nod to the circumstances, he lets the audience in on the joke and cements his Tramp character as a man of the people – simple, direct, and forthright. But it also gives us just enough time to register the humor without lingering on it. It’s a deft touch.

And so he goes on introducing these surreal elements – a diminutive father who frets over his colossal son’s appearance, bulls running out of churches, etc. – building to, arguably, the film’s centerpiece, an unconscious Charlie dreaming of dancing with wood-nymphs.

The quality of that YouTube clip, naturally, does not rival that of Hulu Plus, but we’ll get to that in a second. This is the kind of burst of cinematic joy so common to the silent era but which would gradually erode over the next few decades. There was a purity to the cinema of those years, not just because the actors couldn’t talk, but because audiences were so enamored with the moving picture as a thing unto itself that something as simple as this could be part of a mass-market crowd-pleaser.

Chaplin was inspired by the ballet L’Après-midi d’un faune (The Afternoon of a Faun), choreographed by Vaslav Nijinski for the Ballets Ruses, in which a young faun meets some nymphs in the woods and flirts with them. Nijinski and Chaplin had met a few years prior when the former visited the latter’s studio, and the choreographer later complimented Chaplin on his dancing skills.

From there, Chaplin makes an interesting skid into the plot:

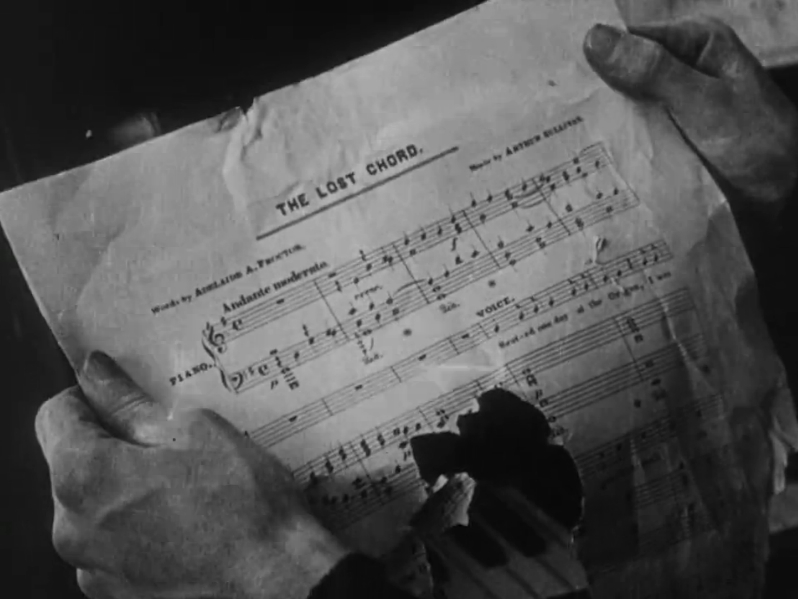

We meet a neighboring farm girl on whom Charlie has a crush, as these things go, and the rich city boy who rolls through town and sweeps her off her feet. And though the plot becomes more familiar, Chaplin’s gags are as fun as ever. In one scene, Charlie and his girl are playing the piano, and think it’s acting up when they hear a nearby goat baaa-ing. And naturally the goat eats the sheet music. Good stuff all on its own, but Chaplin’s smart enough to tag it with just the right name on the piece:

As their story progresses, you can sense traces of the melancholy Chaplin would capitalize on as his career progresses, the feeling that happiness is just out of your reach. This being a short, he finds a way to quickly undercut it and wrap up everything in a satisfying manner, but it doesn’t take much to see how he could have kept that going in a feature (even if his creative block might have prevented such ambition). As it is, it’s a sweet rumination on the way things pass us by, certain fears of inadequacy, and how easily one can become trapped. Don’t get me wrong; the film is still chiefly a comedy and totally a blast, but it achieves a certain pitch towards the end that is not unfamiliar to fans of City Lights or The Kid, which was only two years away.

Presented in HD on Criterion’s Hulu Plus channel, Sunnyside looks pretty great. Whatever print they’re working with isn’t in the best shape, but it still allows for good clarity, and the transfer is relatively free of compression artifacts or blocking. When streamed to your TV, especially, movement looks great and contrast is nicely handled. It looks at least as good as a solid DVD presentation, if not a certain stripe of Blu-ray release defined as much by the elements they have to work with as what they drew out of it.

We’ve yet to find out what, if any, plans Criterion has to bring Chaplin’s short films to Blu-ray, but it’d be cool if they grouped them by studio (do all the First National shorts on one release, the Mutual shorts on another, etc.). I’d also love to see supplemental material on how those institutions defined his work, and perhaps vice-versa, analyzed from both creative and production standpoints. After First National, Chaplin co-founded United Artists, and it’d be interesting to learn how his experience working for a studio affected and emboldened his ability/desire to run one. It’d also be fun to see excerpts from The Afternoon of a Faun, if any exist.

Chaplin’s shorts aren’t always my favorites, but I was rather taken with Sunnyside, and barring any future Blu-ray release, it looks like Criterion’s Hulu channel remains the way to see it. It can be viewed in its entirety on YouTube, but in much lower quality to be sure.

![Bergman Island (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/bergman-island-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/this-is-not-a-burial-its-a-resurrection-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![Lars von Trier's Europe Trilogy (The Criterion Collection) [The Element of Crime/Epidemic/Europa] [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/lars-von-triers-europe-trilogy-the-criterion-collection-the-element-of-400x496.jpg)

![Imitation of Life (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/imitation-of-life-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (The Criterion Collection) [4K UHD]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/the-adventures-of-baron-munchausen-the-criterion-collection-4k-uhd-400x496.jpg)

![Cooley High [Criterion Collection] [Blu-ray] [1975]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/cooley-high-criterion-collection-blu-ray-1975-400x496.jpg)