David’s Quick Take for the tl;dr Media Consumer:

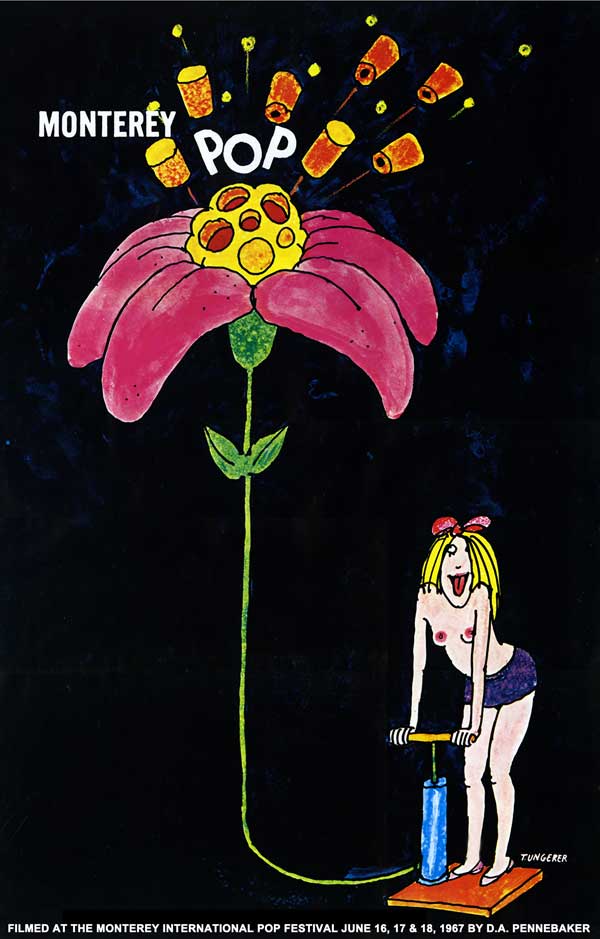

Just as the Monterey International Pop Music Festival marked a pivotal and definitive turning point (in this case, upward) in the cultural ferment of the 1960s, so too the film document of that event, D.A. Pennebaker’s Monterey Pop, initiated a new way of capturing music and its performance for posterity. The weekend-long Festival, featuring mostly West Coast hippie rock and folk combos, with a few international surprises tossed into the mix, was like a meteor that streaked across the sky of an emerging new civilization, illuminating the landscape, brightening the eyes of its witnesses, summoning a potent mix of emotions: joy, euphoria, ecstasy, bewilderment, even dread. The cinematic document, a short film clocking in at just under 80 minutes, that confirmed all those conflicting, incredulous impressions is like the meteorite that survived its hard descent into the atmosphere – potently powerful despite being a mere fragment of the fire-hardened rock that first generated all that friction and landed with such dynamic force. But that meteorite, whittled down to its core essence, gnarled and shimmering with unearthly swirls of color baked to a metallic sheen, still leaves us transfixed whenever its gleam catches our eye, as we contemplate the strange otherworldly origins of this cosmic intruder. Though relatively few among us can vouch that we were actually there to behold the spectacle ourselves, the relic remains accessible to millions, offering sufficient proof that beneficial aliens really do occasionally make their presence known, and in doing so, our hopes that we might someday ascend to soar the interstellar pathways alongside them are affirmed as worthy of our sincere aspiration.

How the Film Speaks to 1968:

There wasn’t all that much of 1968 left when Monterey Pop made its theatrical debut. The New York Times (link below) reviewed the film a couple days after Christmas, just before it went into wider distribution in the early weeks of 1969. Rolling Stone magazine published an article (also linked below) the preceding summer indicating that the footage was being edited for a TV broadcast that was to be shown before it hit the cinematheques. I’m not sure that ever happened, but it was very well known at the time that the Monterey Pop festival had served as a major launching pad for several bands and performers who had since left an indelible impression on the music scene. (Sadly, one of them, Otis Redding, had just recently died in a plane crash a month before the movie’s premiere. Other deaths of key Monterey Pop players would soon follow.) The event also created a template for large scale concerts that assembled lineups of diverse acts seeking to bring people together, enjoying altogether groovy shared experiences with a heavy emphasis on sensory stimulation. If the organizers and bands managed to get rich and famous in the process, well that was all just a nice side effect, but the deeper purpose of these gatherings was the pursuit of some kind of utopian alternative to the exploitative, violent, antagonistic ethos being foisted on the young people of the world by the joyless, square Establishment that resented their indulgence in freedoms of various sorts. Monterey Pop offered a way to bring the “Music, Love and Flowers” message to smaller local scenes across America and eventually around the world, where there was no plausible opportunity to book artists of such magnitude to perform at the local dance hall or fairgrounds. It’s pretty obvious to draw the connection between the success, both artistically and culturally, of the MIPMF and more massive concerts that would take place, for good or for ill, later in 1969. Woodstock and Altamont are the two that most immediately come to mind, simply due to their scale and notoriety, but also because they were both captured in highly memorable and evocative films.

How the Film Speaks to Me Today:

Of the three films just now referenced (Monterey Pop, the eponymous Woodstock and Gimme Shelter, which culminates in the tragic events of the Altamont festival), my clear favorite is indeed Monterey Pop. I think that’s a minority opinion among those who’ve seen and scrutinized all three, and I can easily acknowledge some of the points that would favor the other two over this one. Woodstock is enormous, with a greater roster of musical talent and a longer-lasting cultural impact. I can even accept the argument that the performances of groups that were in both films (especially The Who and Jimi Hendrix) were better in the latter than in the former film. The bands certainly get more time to stretch things out than they do in Pennebaker’s highly compressive approach to editing. As for Gimme Shelter, the sustained focus on a single band (the Rolling Stones) as they toured the country and finally came to a moment of reckoning with the dark forces they dabbled in along the way, offers a more compelling narrative, attended by a host of disturbing implications.

But having conceded all that, Monterey Pop still wins, because in my world at least, it serves up endless helpings of delight. Having first seen it many years ago, back in the late 1970s, and several times since then, I’ve also watched or listened to it repeatedly over the past couple of weeks and I just love it all the more as my familiarity increases. I like the tidiness and efficiency of the whole arrangement – a polite coming together on a warm sunny late spring weekend out on the California coast, the folding chairs neatly lined up, everyone present reasonably close to the stage. The atmosphere is relatively innocent and fresh compared to the grimy flirtations with nihilism and carnage that burble under the surface of Woodstock and erupt with savage ferocity in Gimme Shelter. With just a few exceptions, the longer hair was just beginning to emerge among the men in the audience, or even on stage. The women were brightly vivid, colorful and exuberant, not quite as strung out as they’d often appear to be in the later films. The fashions were still trim and moddish, not yet deteriorated to the full blown shagginess that the hippie vibe would soon collapse into. Most importantly, I cherish the sense that whatever movement this psychedelic happening was trying to promote was still oriented toward the ascension of spirits, minds and bodies, regardless of the elemental chaos unleashed at the end of Hendrix and the Who’s time on the stage – even their acts of destruction had a playful, cheeky attitude. Woodstock had its moments of peace, love and tranquility, but the orgiastic excess of the event leaves me feeling rather blasted by the end of it all. Gimme Shelter basically leads us straight to the slaughterhouse. I enjoy spending my time in the sweet incense and peppermint infused daydream of 1967’s Summer of Love. Monterey Pop, along with select albums from that blissful era (yeah, the usual suspects: Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, Are You Experienced, Absolutely Free, Surrealistic Pillow, The Grateful Dead, Mellow Yellow, Electric Music for the Mind and Body, Flowers, Piper at the Gates of Dawn, and a few others of greater obscurity) remains my quickest ticket back to that little slice of heaven on earth.

The film also stands as a positive example of creative artistic response to a society that was becoming increasingly fucked-up at the time, as the Vietnam War was rapidly escalating, civil unrest was roiling college campuses and impoverished communities, and the authorities were showing a greater willingness to use brutality to impose limits on social movements that they regarded as hostile to their agenda. A wave of assassinations and riots was just around the corner as 67 turned into 68. Monterey Pop wasn’t exactly oblivious to all that – the notes of protest and dissent are there to be sifted out of the generally optimistic Flower Power messaging – but the lyricists weren’t yet consumed by the overtly revolutionary rhetoric that the political Left considered a necessary response to the events of 1968 (especially the triumph of Nixon and his reactionary right wing agenda.) Here we are now, just a few months shy of the festival’s 50th anniversary, and the cycle seems to be repeating itself. It feels like Nixon’s bastard son just got sworn into the Oval Office, and things are on the verge of getting really bad in this country – in some ways, worse than ever. I draw inspiration from the rebuttal that Monterey Pop made as an expression of the counter-culture of its era. I don’t make music any more, but that doesn’t mean I don’t have a voice. As aggrieved as I am to see racism, bigotry and cruelty once more embraced and embedded in the upper levels of our national government, I know that we still have the opportunity to send out that strange vibration, with a new explanation, to put the people in motion. So let’s do what we can to make that California Dreamin’ a reality.

Recommended Reviews and Resources:

- Official site

- Wikipedia

- New York Times (1968)

- Rolling Stone (1968)

- Consequence of Sound (Otis Redding set)

- TheDigitalFix (DVD review)

- Blu-ray.com

Previously: If….

Next: Samaritan Zatoichi

![Bergman Island (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/bergman-island-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/this-is-not-a-burial-its-a-resurrection-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![Lars von Trier's Europe Trilogy (The Criterion Collection) [The Element of Crime/Epidemic/Europa] [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/lars-von-triers-europe-trilogy-the-criterion-collection-the-element-of-400x496.jpg)

![Imitation of Life (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/imitation-of-life-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (The Criterion Collection) [4K UHD]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/the-adventures-of-baron-munchausen-the-criterion-collection-4k-uhd-400x496.jpg)

![Cooley High [Criterion Collection] [Blu-ray] [1975]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/cooley-high-criterion-collection-blu-ray-1975-400x496.jpg)