Ilona: I don’t think it’s going to work out.

Nikander: What?

Ilona: Anything.

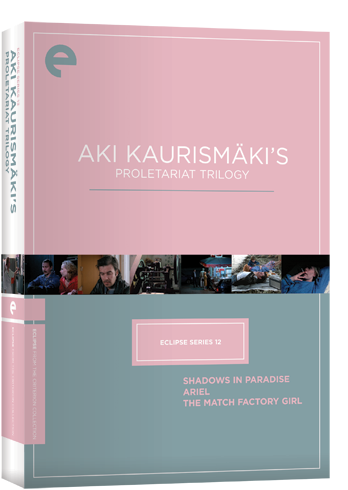

Though it’s just another Monday in the rest of the world, here in the USA, today is Labor Day, a holiday set aside to honor the contributions and sacrifices of working-class folks past and present. Going with that blue-collar theme, this week’s selection for review here seemed obvious enough, so I went with it. Continuing my trek westward through the Eclipse Series, after several weeks spent in Japan and last week’s visit to Russia, now we’re dropping in on Finland. I’m talking about Shadows in Paradise, the first installment in Eclipse Series 12: Aki Kaurismaki’s Proletariat Trilogy. Just the mention of the word proletariat seals the Labor Day connection for me, even though I’d never seen any of Kaurismaki’s work prior to sitting down with this film last week.

I can’t guarantee the same results for the rest of you, but for me, discovering Shadows in Paradise was a case of love at first sight. Even though I’ve never been to Finland (where Kaurismaki lives and situates his characters), I felt an immediate bond of understanding and shared perspective. These chain-smoking, hard-pressed folks eking out their paycheck-to-paycheck existence are my people! The obstacle of a different language is probably the only meaningful cross-cultural gap that exists between me and them.

Well, let me clarify that a bit. In recent years, I’ve somehow managed to nudge my way into a more white-collar way of life, so it’s probably accurate to say that my bond with this forlorn bunch of toiling Finns is based on a sense of shared roots. Seeing them go about their business on the economic outer fringes of mid-80s Helsinki felt very familiar to me, bringing back memories of my own early adulthood meanderings at that time, when I was just starting to figure out how I would establish myself in the manufacturing-based economy of Grand Rapids, Michigan and make my own way in the world. My hunch is that younger viewers, especially those stuck in menial jobs with no clear path to future success or deep seated personal satisfaction from their career in today’s crappy economy, could easily relate to these circumstances as well.

Nikander works on a garbage truck, serving as the #2 in his two-man crew, meaning that he doesn’t drive and is the first one out to connect the dumpster to the mechanical lift. Shadows in Paradise opens with a short run through of a typical day as we see the men make their rounds. Just a few minutes of watching the kind of activity that most movies rarely even notice is enough to convince us how mind-numbingly dull their routine must be. As he scrapes by from day to day, frying up dinners for one in his dingy apartment and alternating between English lessons and bar-hopping as his main recreational activities, Nikander is basically shuffling his way through life, not stirring up trouble but without much of a prospect for improving his situation either. One night Nikander suffers a minor injury while tinkering with his beater of a car, and his wound is noticed by Ilona, a chronically-bored cashier, as she checks out his groceries.

The random encounter sets the two of them up to get to know each other better a bit later on in the film, and if this were a conventional romantic comedy, you’d be safe in assuming that predictably cute hi-jinx and banter between the characters would swiftly follow. Likewise, if this were more of an outlaw caper-type film, something along the lines of Bonnie and Clyde and its many imitators, some kind of deadly/dangerous tensions would develop, thrusting the audience into a shared experience of being desperate outlaws on the lam, with all the escapist fun and simulated adrenaline rushes that such stories often generate.

But Shadows in Paradise avoids both sets of cliches, forging instead into a territory of naturalistic deadpan humor that was highly unique at the time and went on to influence a lot of independent film makers in the years that followed. Nikander and Ilona each suffer setbacks, separately from each other, which put them at a snapping point, leading to dumb, impulsive decisions that force them, only with persistent ambivalence, to rely on each other as they continually fumble in their efforts to communicate or even figure out what’s best for themselves as individuals. They don’t make a particularly charming couple in conventional showbiz terms – they’re about as homely a pair of leading actors as I’ve ever seen – but anyone who’s ever felt so pinned down by circumstances and emotional roadblocks that it becomes impossible to risk revealing what’s in our heart to a person we care about will be able to fondly relate to these exceedingly reticent would-be lovers.

That clip is obviously short and wordless, but effectively captures the awkward static that hangs over the relationship between Nikander and Ilona. Her reluctance to just drop the cigarette and join Nikander’s embrace captures the inhibitions that Nordic culture and working-class life established and reinforced not only in the couple, but in the cast of characters surrounding them.

Those characters include the lunkish, perpetually thirsty Melartin, Nikander’s new-found buddy he meets after going to jail for a bar brawl, Ilona’s two bosses who serve as telling examples of the exploitative jerks who so often find their way into supervisory roles and Nikander’s unnamed co-worker who offers him an ephemeral prospect of upward mobility before making a sad but regrettably foreseeable exit from the proceedings. The handling of this particular character, who passes away from a massive heart attack shortly after revealing his long-delayed aspiration of being his own boss and fulfilling promises he made long ago to his wife, serves as a perfect example of Kaurismaki’s blend of grim humor and societal critique. The appalling irony and abruptness of the old man’s departure makes us laugh until we catch ourselves a moment and realize just how incredibly sad the outcome really is.

Shadows of Paradise carries that ring of truth where as much communication takes place in the silent pauses and diverted acknowledgement of sidelong facial expressions as in the words actually exchanged between characters. With their ambitions only halfway defined, with the meaning and value of events conveyed by the music that happens to be playing on the radio more than any particular declaration of intent by the people themselves, it does seem like there are a lot more shadows than sunshine to be found in this so-called paradise.

But in telling his story, Kaurismaki keeps things moving, making the wise and welcome choice to not pad the film with contrived subplots or attempt to magnify the narrative to make some kind of lofty point. Shadows of Paradise clocks in at a brisk 74 minutes, an inviting length for a feature that I wish more directors would be brave enough to work with. Just enough time for us to enter the atmosphere, get acquainted with its inhabitants, walk alongside them for awhile and see them off to an sneakily absurd, haphazardly pleasant ending.

Unexpectedly rich color schemes and creative framings add to the film’s appeal, demonstrating Kaurismaki’s technical chops to go along with the affection he clearly holds for his protagonists, as flawed and aimless as they may be. It’s not too often we see movies that give unsentimental respect and unvarnished representation to unhip, unglamorous lumpen types like Nikander and Ilona, so common and ordinary in the circles I travel, and so many other places in this world too.

![Bergman Island (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/bergman-island-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/this-is-not-a-burial-its-a-resurrection-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![Lars von Trier's Europe Trilogy (The Criterion Collection) [The Element of Crime/Epidemic/Europa] [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/lars-von-triers-europe-trilogy-the-criterion-collection-the-element-of-400x496.jpg)

![Imitation of Life (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/imitation-of-life-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (The Criterion Collection) [4K UHD]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/the-adventures-of-baron-munchausen-the-criterion-collection-4k-uhd-400x496.jpg)

![Cooley High [Criterion Collection] [Blu-ray] [1975]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/cooley-high-criterion-collection-blu-ray-1975-400x496.jpg)

Not my favorite Kaurismaki film, but any time I get to see one of his films it’s a treat. That said, I love seeing the Helsinki of this era, and the droll, dead pan humor always appeals to me. I would add to your comment that these are your people, the UP has a large population of people of Finnish descent.

Hey Eric – I just saw this comment, sorry it took me so long to notice! :) Though I’m mainly of Dutch descent, not Finnish, I feel an a-finn-ity for the introverted working class folks that Kaurismaki likes to feature in his films. One of my sons’ best friends has the last name Tikkannen too, so you’re right, Finland’s heritage really isn’t too far separated from my world at all!