The world today isn’t very interesting.

Everyone’s dissatisfied.

You ought to try and have a good time.

You’re right. That’s the only way.

I guess that’s about it.

After a weekend packed with tweets, blogs and breaking news about hotly anticipated fantasy/action/adventure/sci-fi movies from the San Diego Comic-Con, I’m sure that some of us are ready to spend a few minutes thinking about poignant, calm, reality-based films for grown-ups as a refreshing change of pace. At least I hope so, since that’s where I’m trying to draw your attention. For this week’s column, I’ve chosen Yasujiro Ozu’s Early Spring, from Eclipse Series 3: Late Ozu. It’s Ozu’s follow-up to Tokyo Story, one of those perennial candidates for “greatest film of all time,” at least within some subsets of the art house crowd. I’ve chosen it for the simple reason that, like Kurosawa’s I Live in Fear back in June, this 1956 release happens to fall right in line with my larger project of watching all the Criterion films in chronological order. I did think about reviewing a comic-themed movie in honor of #SDCC, but William Klein’s Mr. Freedom is as close to that genre as I could find in my Eclipse collection, and I already covered that one earlier this month.

Early Spring also represents a 23-year leap forward in Ozu’s career after last week’s viewing of Passing Fancy, one of his last silent movies. A few small details link the two otherwise unrelated films: first, the male protagonists both have to passively endure some well-deserved face slapping, and second, a character in each film appears on screen with an unexplained eye patch. As would be expected, Ozu’s techniques were further developed and refined over those two decades, but his style remained quite distinctive and consistent as well, perhaps more than any other director over the course of such a long career. The setting of Early Spring has shifted upscale a bit, to an urban working class neighborhood (instead of Passing Fancy‘s shoddy tenement) and the impersonal corporate office spaces of mid-50s Tokyo. The story concerns Shoji, a “salaryman” and war veteran who’s entering his early 30s and settling into the realization that he has a long, slow grind ahead of him as he awaits his turn to climb a few rungs on the corporate ladder over the course of the next several decades.

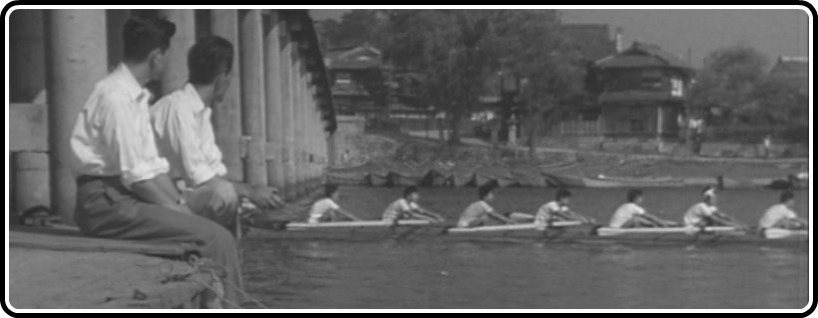

The snippet of dialog at the top of this column is just one of several exchanges that Shoji witnesses over the course of Early Spring, concisely summing up the mood of oppressive futility and weary resignation that the film delivers. This opening clip captures the first six minutes or so of Early Spring, and it’s a lovely (and rather leisurely paced) introduction to this very mundane slice of Japanese life in the midst of their postwar economic rejuvenation. Don’t expect slam-bang excitement here, folks – Ozu’s not the director who’s going to grab you by the collar and plunge you into a whirl of adventure. But savor the subtle details as we start an ordinary day: Shoji and his wife Masako rouse from their slumber, giving small but unmistakable cues of a marriage that’s grown stale and distant; familiar migratory patterns emerge as local breadwinners tread beaten paths en route to the train station, where they each cluster into their chosen cliques, an instinctive safeguard against the dehumanizing effects of their daily commute into downtown Tokyo.

Once we arrive at Shoji’s office, we begin to learn quite a bit about his life. He’s on a management track, likely to be an employee of the Toa Fire-Brick Company until the day he retires, if he so chooses. His friend Miura, hired in at the same time as Shoji, has been laid up with a lung ailment for several months. He has an older mentor, Onadera, played by Ozu’s acting stalwart Chishu Ryu, though with darker hair and a younger appearance than I was expecting based on the elderly characters he played in Tokyo Story, Early Summer and Late Spring. Shoji is integrated into his social circle and generally well-liked, but he’s not particularly seen as a leader or dominant force within the group. Though he’s handsome and seems to have a fair amount going for him, he hasn’t taken that big step to really stand out from the crowd quite yet, and you get the sense that he’s not really clear or confident about where he’d like to take his career. He’s playing it safe, biding his time, observing and holding his thoughts and feelings inside – even concealing them from the viewer. Shoji’s lack of expression and reticence to speak candidly about what’s on his mind is both realistic and at least potentially frustrating. He doesn’t do a whole lot to make himself an interesting character on the screen, but his blank and non-committal affect ends up making him quite believable as a typical guy – and I think “ordinariness” was clearly Ozu’s intention in Early Spring, as in just about all of his films.

The central complications develop when Shoji briefly capitulates one night to arranging a secretive rendezvous with a pretty and flirtatious young woman in his circle, nicknamed “Goldfish” because of her big eyes, her affectionate nature and her reputation for being “best seen from afar.” We already know that Shoji and Masako aren’t getting along, due to general marital fatigue and also the emotional scars wrought by the death due to illness of their son some years earlier that have never really been healed. Goldfish is an amusing plaything for Shoji, but disaffection sets in quickly after he’s satisfied his curiosity, and he shows little interest in prolonging the affair or deepening their relationship in any meaningful way. But the small hints of their encounter have a ripple effect, and soon the gossip and speculation rev up loud enough that Masako begins to harbor her own suspicions. (This plot element makes Early Spring a suitable “Variation on a Theme” of Infidelity, as was discussed in our recent podcast on Wong Kar-Wai’s In The Mood For Love.) Despite his efforts to maintain a passive, implacable surface, Shoji is forced to confront the difficulty of his situation and the lack of a convenient explanation for his recent conduct. Successive scenes throw additional wrenches into the gears of his conscience:

- He hears the news about the widow of one of his slain war buddies who’s remarried and moved on from her first husband’s loss

- He plays host to a couple of drunken pals who remind him to appreciate the comforts and privileges he’s taken for granted and grown bored with

- He listens to Miura’s reminiscence of being hired to work at Toa, seemingly the happiest day of his life – what turns out to be among his ailing friend’s last words

- He offers counsel to a younger neighbor who’s dealing with the unwanted anxiety of his wife’s unanticipated pregnancy and his lack of confidence in meeting the financial obligations of parenthood

- He grapples with the offer from his employers to transfer out of the Tokyo office and relocate to a remote branch of the corporation in the small mountainside manufacturing town of Mitsuishi, city of belching smokestacks and rickety freight-trains and not a whole lot to do…

These central predicaments constitute the core of Early Spring‘s narrative, and without describing how it all ends up, I will forewarn that you won’t get the satisfaction of some big, emotionally wrenching declarative climax. Which isn’t to say that Early Spring lacks an effective punch; it’s there, you just have to let it sink in and hit you. There’s a resolution, and the very mundaneness of the characters’ activities and responses makes it believably satisfying. But I’ll leave it to the readers to determine how much pertinence these kinds of dilemmas have to their own lives. As for myself, I found it all engrossing and stimulating enough to hold my attention over 2 1/2 hours. I’ve lived through my 30s and most of my 40s now, been married for 25 years and I’ve worked for the same employer for over two decades, so there’s a lot of material in Early Spring that I can relate to. Younger viewers, those who mainly seek escapism in their movies, or anyone who’s not been sufficiently oriented to appreciate the craft of Ozu, may want to try some of his lighter, more engagingly entertaining films featured in the Criterion Collection – those mentioned above, or even Good Morning, if you’re looking for something that’s just flat out funny and even raucous by Ozu’s standards. Early Spring is a more bracing concoction, a shot of the hard stuff, like the old and burned out salarymen toss back as they ruminate on where their toil has gotten them. It may not go down so smoothly but it might just be the kind of eye-opener we need to jolt us out of the torpor of a midlife rut. Whatever season of life we may be in, Ozu’s sometimes bleak and sometimes quite amusing depiction of a workingman’s ennui and the plight of the wife who’s pulled along in his wake offers an oblique pointer away from the dead ends and stunted emotions that threaten to engulf us, should we surrender to the tedious monotony that serves as a price tag for the comforts and securities of modern corporate codependency.

![Bergman Island (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/bergman-island-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/this-is-not-a-burial-its-a-resurrection-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![Lars von Trier's Europe Trilogy (The Criterion Collection) [The Element of Crime/Epidemic/Europa] [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/lars-von-triers-europe-trilogy-the-criterion-collection-the-element-of-400x496.jpg)

![Imitation of Life (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/imitation-of-life-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (The Criterion Collection) [4K UHD]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/the-adventures-of-baron-munchausen-the-criterion-collection-4k-uhd-400x496.jpg)

![Cooley High [Criterion Collection] [Blu-ray] [1975]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/cooley-high-criterion-collection-blu-ray-1975-400x496.jpg)

great piece again. I loved this movie a lot and you expressed my very similar opinions in a most eloquent way!