My intention, if it’s financially feasible, is to come back this summer with a film titled Les Cousins, which, while treating a subject completely different from that of Le Beau Serge, will be like the second component of a diptych.

-Claude Chabrol, upon completing Le Beau Serge; 1958

All things considered, Les Cousins will be essentially a perfect Chabrol film, since it will be the reverse of Le Beau Serge.

-Jean-Luc Godard; 1959

Thanks to The Criterion Collection, and now Masters of Cinema, releasing Le Beau Serge and Les Cousins in the same month (though separate releases), with similar packaging designs and complementary supplements, Claude Chabrol’s first two features are now linked in cinephiliac minds in the kind of immediate, visceral way that makes palpable the connection between the two films that has always existed intellectually, perhaps even emotionally. More than simply being the beginning of the career of a major figure in world cinema (unlike the rest of the Cahiers du cinema critics who went on to direct, Chabrol didn’t make a short film prior to his feature debut), the two films play off each other in some very interesting ways, as much of a piece as they are totally apart.

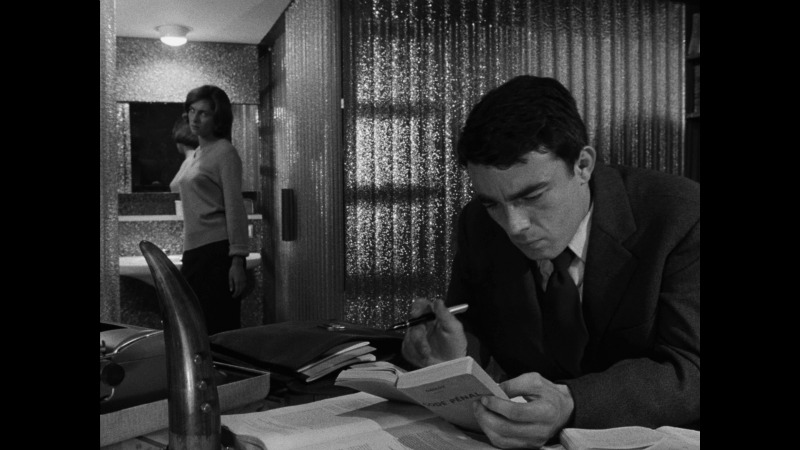

Both films star Gérard Blain and Jean-Claude Brialy. In Le Beau Serge, Brialy and Blain were childhood friends who are now reconnecting; they have a long, if somewhat fractured relationship, and Blain is the bitter, corruptive force. In Les Cousins, they are related (as the title implies), but barely know one another, and only come to live together because of this relation and their attendance of the same university. In both, Blain calls the country (where Le Beau Serge takes place) his home, and Brialy the city (the location of Les Cousins), though in the former, Blain is the most overtly corrupt, morally, while Brialy takes on that role in the latter. However, while Blain’s corruption takes the form of a marriage he detests while remaining absolutely faithful, Brialy’s is by his rampant womanizing, happily seducing (in sometimes fairly nasty terms) whatever woman crosses his path, regardless of who he hurts along the way. The relationship between the two in Le Beau Serge is contemptuous in spite (or, sometimes, because) of a basic foundation of love and respect, while theirs in Les Cousins is much more genial, paving over a bedrock of disdain.

This introduces a welcome tension to Les Cousins, making every interaction fraught with the vast chasm of knowledge, prowess, and savvy that exist between the two, and – in spite of the more melodramatic aspects of Le Beau Serge – it’s a far bleaker affair. Blain comes into the picture as the very face of innocence, and is slowly drawn into some gamesmanship that he is simply not up to. His fight-or-flight responses demonstrate much about him, though even when he feels he’s taking the high road, his utter hatred for everyone involved – himself included – is boiling so fiercely you sit in wonder it doesn’t explode. A great scene has him shuttered in his room while a party rages in his apartment (I’ve been there, for real), denying himself a release of inhibition that he needs so badly, he’s practically sweating. What finally does become of all that internal rage is at once wildly inventive and quietly heartbreaking.

Conversely, in Le Beau Serge, Blain is all explosion, though never in the right directions. He’s furious at Brialy’s character merely for showing up, but not at a rather transgressive sexual encounter that takes place later on, as though he’s delighted that finally someone has stooped even lower than he. It should be said that Blain is an astounding actor, perfectly expressing each character in these two very distinct modes – it’s all in the eyes, as they say, and his are naturally open, vulnerable, so even when he takes turns for the violent, there’s a sadness he can never truly unload.

Brialy is a savvier character, and better suited to his Les Cousins role than that which he takes on in Le Beau Serge. Forever guarded, he’s a protagonist at once closed-off to the audience, and demanded to be sympathized with. Chabrol provides a structure whereby Brialy’s actions come to define him, including his slightly stodgy (“even a bit uptight,” Chabrol notes) nature, and an aesthetic in which he can be framed to create meaning, as his constant meddling goes from being unwanted to desired to unnecessary.

What both films truly highlight is the utter selfishness that takes over many a person in their early twenties, which often takes the form of acting gregarious and generous, but, when it comes down to it, pursuing one’s self-interest before all else. Chabrol was twenty-eight when Le Beau Serge was released, and clearly reflecting on many aspects of his own life through these films (most explicitly in a character losing, as he did, a child so soon after its birth) without ever dipping completely into autobiography. There’s a clarity to the way he expresses his characters’ faults that is either the work of some very developed observation or some especially incisive insight into one’s self, as if he’s looking back in frustration and bewilderment at his own recent past. Whereas Eric Rohmer’s moral tales can feel sometimes clinical and detached, Chabrol gets right up in the muck of self-loathing and -sabotage.

How better to soak in this kind of emotive power than through the magic of Blu-ray? Having appeared already in high definition courtesy of the aforementioned Criterion Collection, which used the same Gaumont restoration we see here, I can’t say there’s a tremendous amount of difference between the two companies (DVD Beaver notes that Masters of Cinema’s release is slightly lighter, which is common to their transfers), and one’s decision to purchase will likely come down to good old region-coding and preference for special features. But both transfers look very good, with solid grain structure that never feels tacked on (lots of variance depending on shooting conditions), really great contrast (there’s a shot near the end of Les Cousins in which Blain walks down a pitch-black street alongside booming-white-light restaurants, and it just looks perfect), and plenty of depth and clarity. Both films are presented in black-and-white in their original aspect ratio, 1.37:1, and these discs are locked for Region B. [screencaps have been taken from the disc, resized and compressed for space, but give a fairly good indication of quality] I found nothing to complain about with regards to the mono audio track.

Now then…the supplements. If you look at the two releases side-by-side, they could almost be mistaken for one another – each includes a long-ish documentary and a short film Chabrol made as part of a larger, omnibus film. In fact, the documentaries are two parts of a whole called Chabrol Launches the Wave, in which various collaborators and other major figures of the period (including Chabrol himself, though this couldn’t have been made long before his passing in 2010) are gathered together to discuss the birth of the French New Wave, which many attribute to Chabrol pulling the trigger on Le Beau Serge (though it had been bubbling for some time). It’s a wonderfully comprehensive look at both the films themselves – part one is more or less about Le Beau Serge, and part two is more or less about Les Cousins, though it helps to be familiar with each – and the larger cultural forces, in French society and also world cinema, and how the French New Wave came about as much because it was an investor’s dream as any creative enterprise. As I said, a familiarity with both films helps immensely in watching either (though particularly the second) part, but having watched the second part first myself, I’d say it stands up reasonably well on its own, if you’re inclined to only buy Les Cousins.

Then on the disc for Le Beau Serge, you get a short film, “L’Avarice,” that Chabrol made for a 1962 omnibus film called The Seven Deadly Sins, and I’m sure you can more or less figure out for yourself how that fits in there. It’s about a group of students who put together a lottery, the prize being enough money to buy an especially attractive prostitute. It’s a lot of fun, suitably light and frothy, runs about 19 minutes.

On Les Cousins, you get another short film made as part of an omnibus (all the rage those days, they were), this one titled “L’Homme qui vendit la Tour Eiffel,” which fed into the larger film, The World’s Most Beautiful Sinners (1964). A quick French translation should give you the general picture, but for those who know no French and don’t want it spoiled, I’ll leave that particular revelation for you to discover, but this was an exceptional treat. Bawdy, fast-paced, and perhaps a little bit insensitive towards Germans (not an unfamiliar sentiment in postwar France, I’m sure), it’s…well, it’s really something. I’d be lying if I said I didn’t laugh, and often, during its 22 minutes.

Both films show very different sides of Chabrol than the one we might conclude after watching Le Beau Serge and Les Cousins. Like his better-known contemporaries, Chabrol too had a very playful side (one impossible to miss in interviews with him), and that, as well as a different aesthetic approach (both films were shot in 2.35:1), provide a more rounded look at the auteur. What’s better, both are presented on these discs in 1080p, and look absolutely gorgeous.

Finally, there are Masters of Cinema’s famous, overflowing, exceedingly generous booklets. You may look at them and say, “32, 36 pages? Eh.” But then you start flipping through them and you’re more like, “32, 36 pages? Damn!” (in a good way). Anyway. Crack open Le Beau Serge, grab yourself some essays by Chabrol, as well as fellow filmmaker/critics François Truffaut, Jean Douchet, and Jean-Claude Biette, as well as snippets from interviews with Chabrol and his unfinished, and as far as I can tell unpublished, memoir. Pull on over to Les Cousins, treat yourself to some pieces by Jean-Luc Godard (in all his wonderfully hyperbolic glory), critic Jean Domarchi, critic and filmmaker Luc Moullet (writing, beautifully and personally, about Les Cousins costar Françoise Vatel shortly after her death in 2005), an interview with wild-man screenwriter Paul Gégauff, and the poem “Le Rat de ville et le Rat des champs” (“The Town Rat and the Country Rat”) by Jean de la Fontaine. Like I said, there is an almost-literal ton of content here, much of it making a rare English-language appearance (some even for the first time), and is demonstrable as ever that when it comes to supplementary booklets, no outfit does it better than Masters of Cinema.

Choosing between the Masters of Cinema editions of these films and the already-released Criterion editions is near-impossible, and one could easily presume that your gut will ably make this call for you. If Chabrol is one of your guys, or you have a great interest in the French New Wave, these are really run-don’t-walk releases. If you own the Criterions and don’t particularly love the films, I can’t say these releases will change anything but your bank account. If, however, you’ve yet to buy any edition of these films, I’d have to give the edge to Masters of Cinema. Even with two very good commentary tracks on the Criterion editions (and I am a commentary guy through and through), there’s a lot of analysis and biographical information spread amongst the supplements here. While I haven’t the time or particular inclination to go bit-by-bit for repeated tidbits, the experience of moving through each disc was at least a draw, and with the MoC releases, you get two short films in high-definition to boot.

Claude Chabrol may not quite have the reputation of a Godard, Truffaut, Rivette, etc., but these two releases from Masters of Cinema make a powerful case for his importance, both as an artist and a historical figure. If you’ve yet to make your acquaintance with him, these make for a very good introduction.

![Bergman Island (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/bergman-island-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/this-is-not-a-burial-its-a-resurrection-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![Lars von Trier's Europe Trilogy (The Criterion Collection) [The Element of Crime/Epidemic/Europa] [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/lars-von-triers-europe-trilogy-the-criterion-collection-the-element-of-400x496.jpg)

![Imitation of Life (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/imitation-of-life-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (The Criterion Collection) [4K UHD]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/the-adventures-of-baron-munchausen-the-criterion-collection-4k-uhd-400x496.jpg)

![Cooley High [Criterion Collection] [Blu-ray] [1975]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/cooley-high-criterion-collection-blu-ray-1975-400x496.jpg)