The release of a second Criterion Collection title by director Georges Franju sparks a significant enhancement of my interest in his work. Back in the summer of 2011, when I reviewed his earlier film Eyes Without a Face, Franju the auteur didn’t make much of an impression on me, at least not to the point that I gave him a whole lot of attention or consideration in my essay. Even though I greatly appreciated that movie, and noted the powerful effect of an earlier documentary of his (The Blood of Beasts) had in serving as commentary on the gruesome crimes committed in the main feature, it’s clear to me upon re-reading it that I was too casual in my assessment of the artistic force behind those two films.

But the opportunity to view Judex, a curiosity-provoking item that came out just last week, has definitely done much to fixate my attention on this unique visionary of early 1960s French cinema. That’s primarily due to the fact that this is a more comprehensively loaded edition that draws more attention to the director’s broader career. Maybe Criterion thought the extra goodies were necessary to bolster sales of a film that is certainly more obscure and less celebrated than Eyes, which is beloved in almost equal measure by classic art house and more cerebral-minded fans of vintage horror films, and has benefited from greater exposure in a variety of formats over the years. Or maybe they just dug deeper into the archives out of appreciation of Franju and his own connections to the glorious early years of French cinema. The rich array of supplements include two short subjects directed by Franju that each offer indirect insight on the main feature by hearkening back to the first two decades of the 20th century. An hour long overview of Franju’s career and an interview with Judex‘s most compelling performer round out the set.

All that extra information about Franju definitely got me to sit up and take notice of his compelling aesthetics. However, there’s also something to be said about the cumulative impact that accompanies a director’s second Criterion entry, in which a fan like me comes to understand that, far from regarding Eyes Without a Face as a fortunate one-off that stands out from an otherwise undistinguished career, Franju’s work provides a very important and enjoyable bridge between two fascinating eras in the evolution of film – the age of silent expressionism that provided inspiration and a basic vocabulary that Franju worked with throughout his career, and the reclaiming of creative freedoms that picked up steam in the early 1960s through the emergence of various New Waves and a loosening of the grip from government and industry censors.

Judex is based on a series of films, more than five hours long when viewed sequentially, shot by the pioneering French director Louis Feuillade in 1914 but delayed by the outbreak of the Great War and finally released in 1916. The character for whom the films are titled is one of the earliest examples of a caped and masked heroic figure captured on celluloid. Apparently Feuillade was making amends of a sort in creating this character, a mysterious avenger and righter of wrongs, since his previous productions Fantomas and The Vampires drew criticism for excessive celebration of wickedness, at least in the eyes of some. The gist of the story is that Judex was the secret identity of a young man out to avenge the death of his father, driven to suicide by an unscrupulous banker named Favraux. In the course of his mission, he must deal with the distractions of his infatuation with Favraux’s beautiful daughter Jacqueline and a criminal gang led by a cunning and diabolical female adversary, Diana Monti. Of course, this basic narrative structure has by now become so dominant in today’s comic-book driven movie industry that I consider Judex mandatory viewing for anyone interested in the development of the genre. This clip, the only one I could easily find on YouTube, gives a brief sample of the original, and it’s of interest to those who’ve seen Franju’s remake because it’s a direct predecessor of a scene that’s been updated (and improved) in the newer version.

Franju’s initial desire in creating a tribute of sorts to Feuillade was to remake Fantomas, whom he regarded (quite reasonably) as a more interesting character than the fairly bland and one-dimensional Judex, offering greater possibilities for a new adaptation, but the rights to that property were not available at the time, so he settled for the best alternative at his disposal. He had already directed a pair of films between this one and 1959’s Eyes Without a Face, and now I’m seized with curiosity to find out if they’re any good. As might be expected, given the less than ideal circumstances dealt to him in acquiring the story rights, Franju took a loose but highly selective approach to the source material, compressing the long meandering saga into a swiftly progressing 97 minutes that definitely feels like a litany of pivotal plotting points, presented without feeling the need for much in the way of rational exposition. The characters of Franju’s Judex simply leap into action, driven by motivations left largely unexplained other than the very apparent cravings for revenge, quick fortune or blind hatred that we see emoted on the surface from one scene to the next. As one who’s of the opinion that we have way too much psychoanalyzing and an unhealthy emphasis on back story in most of today’s heroic fantasy epics, I found this approach extremely satisfying and intriguing. Franju seems to understand that many in the audience really have no interest in learning about why these characters behave the way they do – we’re pleased just to see them project those raw emotions, in their pure form, conjuring up fantastic visions and creating memorable exchanges along the way.

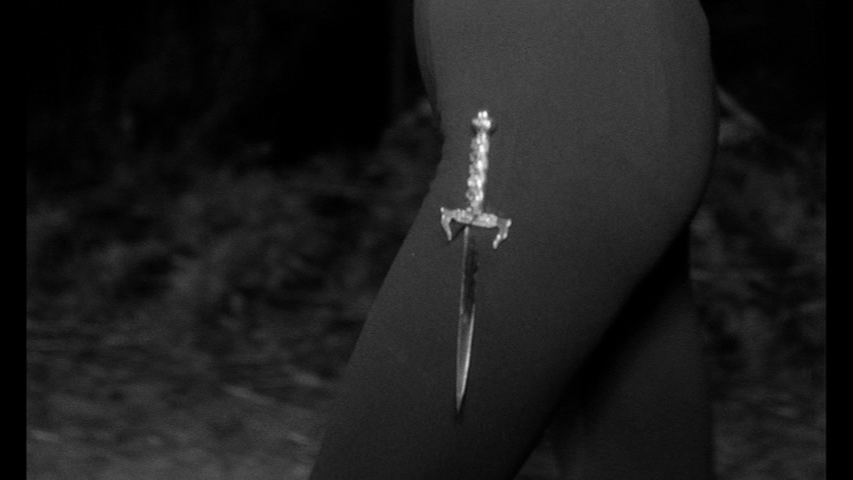

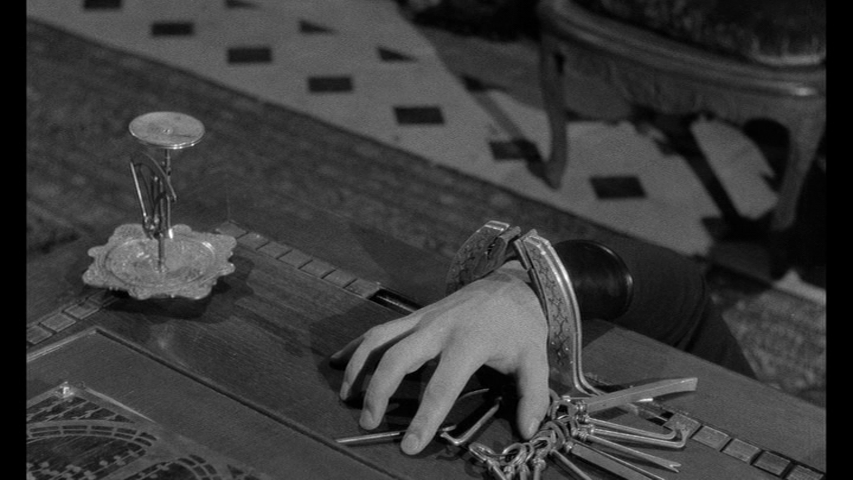

And this is exactly where Judex excels. In its juxtaposition of light and shadow and the calculated imposition of threats, illusions and false personas on the respective villains and protagonists, viewers are plunged into a whirlwind of intrigue and mystery that hardly needs to rely on “making sense” in order to sell itself as a worthwhile pastime. Mountaintop hideouts, secret passageways, weird technology simultaneously arcane and futuristic, a straightforward and deeply beguiling manifestation of authentic, non-ironic cloak and dagger, all this and more make Judex an intoxicating treat that invites us to stop and stare. The beauty of innumerable moments has lingered heavily in my imagination over the past several days, and the sheer unpredictability of what’s about to happen next as the movie unfolds in a first watch makes me very reluctant to say a whole lot more about the plot. After all, I expect that most readers will have not seen this film yet and I recommend going into it as blind to the storyline as possible. But if you do need a little more substance to go on in deciding whether or not Judex is deserving of your attention, allow yourself to peruse this gallery of gorgeous stills that I’ve captured from the DVDs in this dual-format edition. (Yes, this is my little howl of protest at the demise of that marketing strategy on Criterion’s part.)

Yeah, I know that all those images brazenly contradict what I said above about going in blind, but I don’t think they really give too much away… and there are plenty more screencaps that I could have posted. In particular, the pics of Francine Bergé (the sexy brunette in the catsuit) exerted a profound attraction, to the extent that I posted a bunch of them on my long-neglected Tumblr page. (But hey, at least now I think I may have found a use for it.) Cast in her role by Franju almost at first glance because she possessed the “evil look” that he was seeking for the part, she elevates the whole project with her unmitigated villainy, relishing the opportunity to spread malice of a most stylish sort for its own sake. Interviewed some fifty years later in one of the supplements, she’s still a radiant beauty who speaks with great affection for Franju and also Edith Scob, the fair maidenly presence who provides the other vital link to Eyes Without a Face. It’s clear from her recollections that for her, for Franju and probably numerous others involved with this project, Judex was a labor of love, a fondness that, after decades of neglect and obscurity, is happily requited at long last in this tantalizing new release from the Criterion Collection.

![Bergman Island (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/bergman-island-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/this-is-not-a-burial-its-a-resurrection-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![Lars von Trier's Europe Trilogy (The Criterion Collection) [The Element of Crime/Epidemic/Europa] [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/lars-von-triers-europe-trilogy-the-criterion-collection-the-element-of-400x496.jpg)

![Imitation of Life (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/imitation-of-life-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (The Criterion Collection) [4K UHD]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/the-adventures-of-baron-munchausen-the-criterion-collection-4k-uhd-400x496.jpg)

![Cooley High [Criterion Collection] [Blu-ray] [1975]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/cooley-high-criterion-collection-blu-ray-1975-400x496.jpg)