The Criterion Collection’s July 2017 lineup features some potent and heavy material, among the heftiest offerings in terms of sombre meditations on the bleaker aspects of the human condition. From the raw depiction of postwar trauma in Roberto Rossellini’s War Trilogy, to the philosophical depth and gravitas of long-coveted titles from Robert Bresson (L’argent) and Andrei Tarkovsky (Stalker), nobody can accuse Criterion of serving up lightweight fluff in the middle of summer.

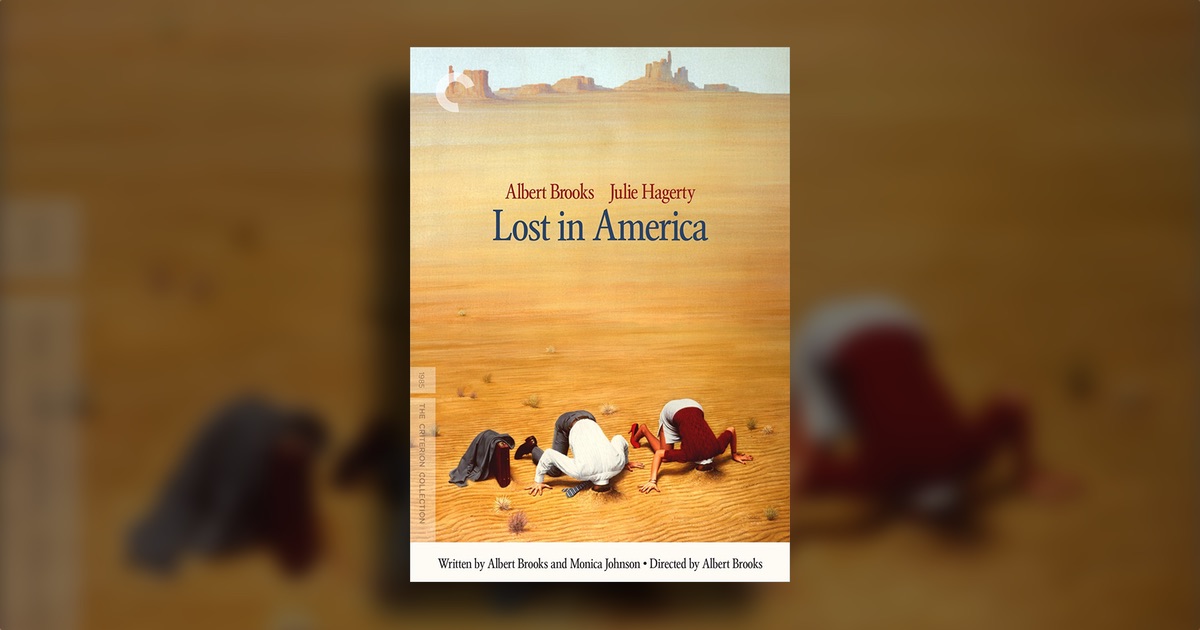

And then there’s Lost in America, a short and breezy topical comedy from the mid-1980s that might come across, at least on the surface, as the class clown of the bunch. Alongside the grim wartime, post-apocalyptic and crime-infested scenarios addressed in the other July releases, Albert Brooks’s brisk social satire of the moral vacuity of the yuppie ethos runs the risk of feeling relatively benign, even inconsequential.

That admittedly superficial take on Lost in America is a fair description of my initial impression when I heard about the pending release, based on my recollections of seeing the film on VHS many years ago, when the wardrobes, vehicles, hair styles and overall cultural attitudes were a lot more contemporary and didn’t have as much of the “time capsule” aura about them as they now seem to carry. I was perfectly open to seeing it get the Criterion treatment, as I knew that Brooks’s style of humor delivered a bit more depth of insight and sophisticated nuance than the average comedy from that (or most any other) time period. But in comparison, I figured that this selection would slide past the senses almost effortlessly, destined for an enjoyable one-time viewing before I nestled it back on the shelves to sit there probably unwatched for the next few years at least. Well, I got more than I bargained for.

The film tracks a couple’s rapid descent from upwardly mobile affluence into a bewildered, aimless journey of “finding themselves,” forcibly disrupting their materialist agenda due to abruptly thwarted career goals and sudden, self-inflicted financial ruin. Because the husband and wife at the center of the story are both thoroughly self-absorbed and so easy to relate to for the movie’s targeted audience, Brooks chose wisely to play it up for laughs (of which there are plenty), but the chuckles are accompanied by a rich side serving of pathos too, assuming that we’re able to personally latch on to one or the other of the two main characters.

David and Linda, the husband and wife endlessly striving to better understand their inner drives so that they can maintain at least a surface appearance of New Age emotional equilibrium, experience quite an appalling series of unfortunate events over the course of their brief sojourn into the Southwestern American landscape. After selling their house in anticipation of David’s seemingly inevitable promotion, their plans for ascending the next rung up the corporate ladder come to a screeching halt just as they’re about to push the launch button. The head honcho has a different vision for how to deploy David’s talents as an advertising creative type, and that basically blows the circuits for a devoted careerist who comes to see himself, transformed by the shock, into an individual both “insane and responsible; that’s a potent combination.”

Is it on an insane, deluded whim that David implores Linda to quit her job just as spontaneously as he managed to get himself fired? Or was his impulsive change of direction a deeply responsible and rational choice, given the rude awakening that his boss’s decision inflicted upon him? However you explain it, David’s persuasive pitch that convinced Linda to cash out all their material possessions in order to purchase a top of the line Winnebago and head out into the wide open spaces of the great American landscape alters their destiny. Only it’s into a process of personal transformation that neither of them could ever have imagined, leading to an outcome that is depressingly inevitable. Their spontaneous, desperate outburst of faux rebellion is the result of an inexorable drive to at least play around with the idea of dropping out, a brief blossoming of seeds planted back in the late 1960s when the young lovers were first coming of age, their mildly expanded consciousness shaped by the rumbling motorcycle engines and wide open landscapes of Easy Rider.

We can never get far enough below the surface of this pair to draw a conclusion on the answer to those questions, but viewers of a certain age and/or experience will recognize that Brooks is holding up a mirror in which we will catch our own fleeting, furtive gaze. Out of that cathartic moment, we’re invited to consider similarly reckless, all-or-nothing gestures that we’ve made along our own journeys in life. There may even be a few who watch this movie who recognize that they too are standing on the very brink of their own desperate lunge into the void, as they contemplate a radical break from the predictability and convenient conformism that have dictated their own steps over the past however many years before they finally reached their pivotal snapping point.

But getting back to the particulars of this film… Lost in America strikes a wonderful, amusing balance between the generic underlying anxieties experienced by so many inhabitants of corporate beehives past and present, and the particular cultural signposts of the era in which the film was made. The decked out Winnebago, featuring all the modern conveniences (I especially love the microwave oven with a browning element), the opening ambient soundtrack of a Larry King radio interview with Rex Reed, and an extended cameo appearance by the neon-drenched Glitter Gulch environs of Fremont Street in downtown Las Vegas all ring resounding chords in the memories of folks who lived through that era. For those who came into this world in or shortly after the ascendancy of the Reagan years, this is about as evocative and revelatory a journey to that era as one might hope for in a film of similar length, especially if one is trying to get a handle on what kind of mentality is driving so many of the Baby Boomers whose conflicted social and economic perspectives now set the tone for our present state of political dysfunction.

So yes, there is an ample buffet of food for thought to be found in this movie, with a variety of practical applications and clarifying observations about the way we continue to live today that can easily be extracted, and laughed about. Albert Brooks and his screenwriting collaborator Monica Johnson string together highly entertaining sequences loaded with memorable, quotable lines that hold up well and continue to offer fresh amusements even after multiple viewings, as I discovered after giving it a few spins over the past two weeks. The supplemental features are definitely on the skimpy side. A fine essay by Scott Tobias is nicely placed in an insert designed to look like a mid-80s advertising layout. But other than a trailer, there’s nothing along the lines of archival material to be found here, probably the result of the film’s economical story telling and unobtrusive entry into the pop culture lexicon. All we get, is a series of short interviews, each recorded earlier this year specifically for this disc, with Albert Brooks, his on-screen wife Julie Hagerty, and a few of his professional colleagues who also happen to make brief appearances in the film. Their anecdotes draw our attention to the subtle enjoyments to be found upon further reflection of David and Linda’s epic transcontinental journey, and also relate some charming details about how the movie was made.

But let’s tell it like it is. Lost in America, unlike the other titles I mentioned up top, isn’t really the kind of flick that benefits from the “film school in a box” package that Criterion is most renowned for. Still, it’s a great release, accessible to a wide audience, one that I’d enthusiastically recommend adding to one’s home video library and showing to a group of friends ready to enjoy a relatable feast of wit and wisdom, that delivers its fond but skewering indictment while leaving a smile on their faces.

![Bergman Island (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/bergman-island-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/this-is-not-a-burial-its-a-resurrection-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![Lars von Trier's Europe Trilogy (The Criterion Collection) [The Element of Crime/Epidemic/Europa] [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/lars-von-triers-europe-trilogy-the-criterion-collection-the-element-of-400x496.jpg)

![Imitation of Life (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/imitation-of-life-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (The Criterion Collection) [4K UHD]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/the-adventures-of-baron-munchausen-the-criterion-collection-4k-uhd-400x496.jpg)

![Cooley High [Criterion Collection] [Blu-ray] [1975]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/cooley-high-criterion-collection-blu-ray-1975-400x496.jpg)