The Tarnished Angels, Douglas Sirk‘s 1957 masterpiece, is a film with a thousand mysteries, yet nary an unanswered question; an explicit melodrama and yet a deeply felt examination of repression. It exists somewhat on the continuum of mid-1950s, studio-funded pulp adaptations, high on sex and thrills, yet it sacrifices none of that in also being an extraordinary portrait of loneliness, isolation, addiction, and lust. Which, I guess, in a sense, makes it kind of a perfect movie, if you allow for a little imperfection.

Sirk wanted to adapt Faulkner’s 1935 novel Pylon since his days in the German studio system, finally finding an easy avenue when he became an established Hollywood picture-maker. Collaborating with screenwriter George Zuckerman (one of several holdovers from 1956’s Written on the Wind), he created something that had to be, in his words, “complete un-Faulknerized,” yet so true to the source that the author reportedly favored it above all other adaptations of his work. I haven’t read the novel myself, but even a quick perusal of its plot and characters make obvious the changes that would be needed to satisfy the Production Code (though it’s amazing how much they ultimately got away with). The rather unusual relationship the group of airplane racers share stands out, while other changes were the sort of inventions that made a guy like Sirk a guy like Sirk.

The novel rather famously describes its protagonist, an alcoholic, unnamed reporter, as frail and “ghost-like,” while Sirk went ahead and cast his favorite leading man, Rock Hudson, the very paragon of almost comically-exaggerated masculinity. What Sirk loses in an immediate archetypal identification of his protagonist’s struggle, he ultimately gains the moment Hudson has to do any actual acting. His eyes reveal a perpetual vulnerability. His voice is as deep and resonant as it is on the verge of complete breakdown. His stature allowed him to command a room, but his manner often precluded it, and Devlin’s battle between taking the reporter’s role as observer and his desire to lash out at anyone and everything is a constant source of tension.

Yet despite being the film’s ostensible protagonist, we really come to understand very little of Devlin. He describes the group of plane-racers as gypsies, beings from another planet, yet he is as much an outsider in their world as they are in his. Sirk apparently read a poem to Hudson to give him the proper perspective on his character – although he was the protagonist, he was not the hero of the story. Sirk, wisely, did not carry this too far, allowing Hudson to share some of Devlin’s own illusions as to his level of importance. It’s a brilliant bit of direction, and gives Devlin a level of authenticity that’s difficult to fake.

This is beautifully established by the opening scene, as Devlin wanders about the carnival in which much of the film’s action will take place, supposedly looking for a story, yet quick to intervene when he comes upon a young boy being taunted by an older man who’s questioning the younger’s parentage. This conflict could be a whole story itself (in no small part because Christopher Olsen is so good as the boy), if not for Laverne (Dorothy Malone). She may just be the parachute jumper, a sideshow compared to her husband, Roger (Robert Stack), and his spectacular races, but her wandering desires ensure she’ll always have his attention. That their son’s genetic line should be in question is due to the third of their party, mechanic Jiggs (Jack Carson), whose undying love for Laverne will never overcome the scraps of affection Roger throws her way. His reliance on the affections of others will factor heavily into his final scene, a moment so heartbreaking it could only be done as simply as it is here.

Sirk recast several of his Written on the Wind players – Hudson, Malone, and Stack, along with a handful of character actors – which made for a hell of a publicity stunt for a studio eager to capitalize on that film’s success, yet it is difficult to imagine any of these characters apart from their performers. Most of all Malone. Angels asks a lot of an actress, forcing her to look at once older than she is without playing an older woman, retain a fierce sexuality while coming off, from time to time, a little pathetic. She is the engine of the film and its victim. At once its most tawdry, noble, and human element. Anyone looking at this story objectively would make her the protagonist, but her stature gains tremendously from an ounce of distance. Devlin would make a rather poor supporting character under her watch. Malone’s rendering is a woman arrested in a schoolgirl state, still doe-eyed around the man whose photograph she loved first, yet all too aware of how she’s suffered for it. She makes every decision for her son, except for the ones that really matter.

While the title is a plural, it really comes about in situating Roger amongst an entire generation of war heroes, lost without a war. In a 1980 interview included on this disc, Stack relates his character’s fate to that of so many Vietnam veterans, and the movies have demonstrated that Roger’s struggle is indeed an inevitable casualty of all wars. All he wants to do is fly. In the war, he could be lauded for it; now, all he can do is go in circles, hoping the prize money will be enough to get him and his small crew a meal and enough gas for the next leg of the journey. He’s given the least amount of explanatory dialogue, but that’s for the best – the stoic, noble Prince is not supposed to reveal his weakness. What emerges comes out through the cracks, and Stack beautifully plays a man whose structure is crumbling.

It is assumed, given this set-up, that Devlin, too, will have some love to give, or at least some desire, and Sirk wastes little time getting us there. Devlin has no sooner met these gypsies than offered them his place to stay, even leaving it in their care while he does some shopping (perhaps he even gave them the key). The rush of intimacy (emotional, for now) that Laverne offers Devlin the moment he walks in the door may be typical of her, or he may have provided an open ear at just the right point. We’ll never know. Devlin is at once entirely incidental to the proceedings, never changing the course of the shreds of plot until the final moments of the film, and perfectly central to it. As most writers do, he tries to use his job as an excuse to spend time with the gang, except his editor is having none of it. No matter. Devlin would sooner lose his job than miss a moment of this. He is as addicted to observing their lifestyle as they are to living it. Perhaps he feels he can live it, too, if only for a short while.

By the end, everyone except Devlin will be poorer than when they started, yet he is left with less to hope for from his future. They are forever on the move; he is static. He’s even left on the very fairgrounds on which the film opened. The carnival has moved on. He is waving from the airfield to his latest, departing, obsession, perhaps fashioning himself like Bogart at the end of Casablanca, who gave up his own happiness at an airfield for the greater good of someone else, and indeed the world. Devlin’s sacrifice is not nearly as noble, though given his illusions, it could seem to be. But Bogart walked confidently into the distance, at “the beginning of a beautiful friendship.” What’s Devlin got? He even has to be restrained from standing too close to the plane. Their lifestyle is deadly, we have learned; contact is dangerous.

What transpires between Devlin and Laverne’s night to remember (he brags, the next day, that he “sat up half the night discussing literature and life with a beautiful, half naked blonde”) and their tear-free farewell is so rarely defined yet beautifully indelible. They share one kiss, but they could hardly be said to be in love, or even overly fond of one another. Devlin’s attraction to her is a mix of lust and pity. He stops in his tracks as she undresses in front of him, but has nothing but contempt for every decision she makes. Ain’t that always the way. Sometimes his assistance is a life- (or at least a dignity-) saver; other times it’s intrusive and unwanted. When she lashes out at him later in the film, it feels entirely earned, but we’d have a hard time saying exactly why. Perhaps because he merely acted as though he belonged, when their separation was inevitable. Perhaps their momentary bond made Laverne more guilty than fulfilled. Maybe he just hung around too much. The people in The Tarnished Angels are not specifically motivated, yet their life experiences make credible their actions.

That’s bold screenwriting, to say without saying. It defines melodrama, and it defines Sirk. Speaking of his actors in one of the supplements on the disc, he said, “Split personalities require a certain eccentricity, a certain illogical ways of their behavior. To achieve this, I needed a new type of actor. I needed actors who weren’t established stars, because [stars] weren’t eccentric…[they] conformed to the public’s expectations.” The irony, of course, is that Hudson and Malone in particular were rather big names by 1957, and Sirk uses that to his advantage, twisting those expectations with actors still too young to know better in an industry increasingly open to wildly diverse modes of expression. In his most popular collaborations with Sirk, Hudson had been an ideal, either a man redeemed (Magnificent Obsession), a model (All That Heaven Allows), or filled with decency yet harboring a secret passion (Written on the Wind). Devlin projects all of those traits, but contains none of them. Universal made some attempts to salvage Hudson’s image, mostly in giving him better clothes, but their efforts seemed to mostly come and go without effect. At best, he’s selfishly motivated to selflessness.

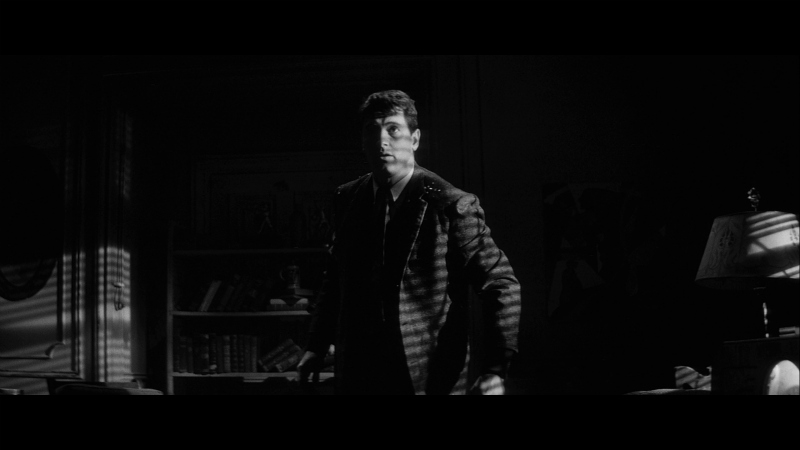

It will come as little surprise to fans of Sirk or Masters of Cinema that The Tarnished Angels looks spectacular on Blu-ray. The MoC gang really knows how to milk these studio-provided HD masters for all their worth, not allowing the tendency toward heavy contrast to outweigh the earthier qualities of the film itself. Grain is very light, but appropriately textured, and a small flaw here or there gives it that great human touch. For the most part, though, it barely has a speck on it, is remarkably free from damage. Sirk and cinematographer Irving Glassberg (who did few, if any, other films of note) boldly refuse the standard tack of lighting for the environment, letting their sources come from wherever they damn well please, and MoC lets that richness sing here. Despite of being full of such beautifully-composed shots, the film is really more about the movement in the frame, and what’s changing, than how characters are precisely posed, and the transfer doesn’t lose any of that richness in such a flurry of movement. They are forever in motion, impossible to ground.

Stories vary about the extent to which Sirk was eager to shoot in CinemaScope. He later said (in an interview one can find on the Criterion edition of All That Heaven Allows) that it was “really of no advantage,” and better suited to frescos and costume dramas. Nevertheless, he made three other pictures (Interlude, Battle Hymn, and the forthcoming-from-MoC A Time to Love and a Time to Die) in the format. Adrian Martin, on his commentary track, talks about how Sirk found the whole process difficult as hell, finding the proper space and all to get actors in the frame without leagues of dead space, but says he ultimately chose the format to better photograph the airplane races. No doubt they are spectacular scenes, and Sirk seems to have hardly missed a beat in transitioning from cropped Academy widescreen and the much wider CinemaScope; indeed, his assertion that it changed relatively little for him plays out, as his compositions remain as assured as ever.

When one thinks of themes of isolation and alienation in cinema, the frame is usually used to show the distance between characters, and, when they do interact physically, the awkwardness that transpires. Sirk plays around with some of this, but when there is distance to explore, it’s part of an overall blocking scheme – characters will start near to one another, then drift apart. Conversely, if they start far apart, it often suggests a longing to be nearer – the shot of Devlin seeing Laverne undress, then cutting to her undressing relates them with incredible power, even though they’re occupying diametric spaces. When they do embrace, it is as though each is filling an empty space for the other. It becomes as though they want to mold into the same person. Their individual isolation is made more transparent and palpable by their grasp for human contact.

And, man, you want special features? This disc has special features coming out of its ears (I’ll let you work that one out). They’re all ported over from other – mostly foreign – DVD editions of the film, and I really have to commend MoC for their effort in gathering them together. The key feature is the commentary by Martin, as sharp and well-read a scholar as you’re likely to come across, and leagues livelier than most. He does what all great scholarly tracks do, merging analysis with research to create a personal, informative perspective.

Providing further scholarly input, a half-hour video piece centering around an interview with Cahiers du Cinema‘s man in Los Angeles, Bill Krohn, is also provided, as is immensely satisfying in its own right. There isn’t a lot of overlap between his thoughts and Martin’s – although each touch on similar themes within the film, they pick different moments to illustrate them. As these sort of things go, I do wish it was a little longer – Krohn says he could spend fifteen minutes talking about one gesture in the final scene, and I’d love to hear that.

The remaining special features feature interviews with the creative personnel, starting with an unusually long discussion with character actor William Schallert. He plays a colleague of Devlin’s at the newspaper – a bit part, mostly – and also featured in Written on the Wind, in addition to roles in numerous other films throughout the year. However, just because you probably don’t know his name doesn’t mean this isn’t a very interesting 18 minutes. He sticks to the professional side of the craft, a nice change of pace for these sorts of interviews, and shares a lot of great anecdotes of working with Hudson, Sirk, and many others.

Finally, as far the disc content goes, there’s a collection of archival interviews with Sirk, Hudson, Stack, and Malone (plus filmmaker Andrea Arnold thrown in for good measure) that is absolutely invaluable. In the commentary track for Criterion’s edition of Magnificent Obsession, film scholar Thomas Doherty speculates about the extent to which Sirk’s reputation amongst cinephiles was established because, in interviews, he was able to discuss art theory and history so in depth that the affection critics had for the man quickly transferred to his films. It’s not an absurd theory – you can see how that happens in contemporary cinema with blogger-friendly filmmakers like Rian Johnson and Duncan Jones being elevated to the status of greats largely because of their online prominence – even if I don’t think it tells the whole story (certainly not for Sirk’s lasting legacy), but it is apparent even from these short snippets just how intelligent he was. Stack also comes off much more insightful than I ever would have guessed. But they’re all worthwhile, even if I wish they were featured in a longer piece, as they are sometimes edited down quite harshly.

And then the booklet, in which Sirk does get some more room to speak (excerpted from Sirk on Sirk: Conversations with Jon Halliday), as does Faulkner. Tag Gallagher contributes an excerpt from “White Melodrama” (which you can read in its entirety here), MoC presents a fantastic 1958 review by Cahiers du Cinema‘s Luc Moullet, as well as an article from Air Progress magazine discussing the gear head side of things. The latter is especially welcome, as it gives a wider context to the film’s setting, and just putting the thing as a whole in perspective – Douglas Sirk is never named (journalist Tom Henebry refers to him only as “the director”), and the stars are only mentioned in the final paragraph (“Rock Hudson usually makes out pretty well in these situations,” he concludes, “but see the movie to make sure”). These features are usually the result of an enterprising publicist at the studio, and while a modern feature would ensure such items are mentioned at the top of the story, it’s kind of refreshing to see a piece with its readers interests at the forefront. It’s also just damn well written. Last, but certainly not least, we get a 1971 essay by Rainer Werner Fassbinder, a man with no small amount of appreciation for Sirk. It’s a beautiful piece of literature altogether.

I’m sure you can tell by this point that my affection for this film is virtually limitless. Anyway, if there is a limit to such things, I’ve yet to find it. The Tarnished Angels so simply evokes so many timeless themes, all wrapped up in a tawdry, exploitation-for-the-masses set-up that Hollywood has always reveled in. It’s a bold departure for Sirk from his usual suburban settings, yet the atmosphere of the carnival seems drenched in life experience. I’m not near enough an expert to say. But it is true to a certain life experience, those fleeting days that become defining moments, yet will scarcely affect your future circumstances. It’s a beautiful film, and not just in the typical it-looks-pretty kind of way (though, boy, does it), but in its very soul. I am incredibly glad that Masters of Cinema made it available on Blu-ray, for the first time anywhere in the world at that (making it only the second Sirk film to hit Blu-ray at all, shockingly). A “recommendation” is not enough. This is essential cinema.

![Bergman Island (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/bergman-island-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/this-is-not-a-burial-its-a-resurrection-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![Lars von Trier's Europe Trilogy (The Criterion Collection) [The Element of Crime/Epidemic/Europa] [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/lars-von-triers-europe-trilogy-the-criterion-collection-the-element-of-400x496.jpg)

![Imitation of Life (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/imitation-of-life-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (The Criterion Collection) [4K UHD]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/the-adventures-of-baron-munchausen-the-criterion-collection-4k-uhd-400x496.jpg)

![Cooley High [Criterion Collection] [Blu-ray] [1975]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/cooley-high-criterion-collection-blu-ray-1975-400x496.jpg)