Of all the individuals ever assigned the task of sitting alongside the camera operator to direct a motion picture, I feel confident saying that none have been subjected to closer analytical scrutiny and more widespread popular acclaim than Alfred Hitchcock. Routinely considered one of the greatest, if not the preeminent, cinematic geniuses of all time, the “Master of Suspense” boasts an unparalleled litany of superlative achievements dating back to the silent film era and continuing over the course of five decades. His career can conveniently be broken down and digested in a handful of different eras, with most Hitchcock fans beginning their acquaintance with his work based on the legendary run he enjoyed through the 1950s in perennial “greatest film of all time” candidates like Vertigo and Rear Window, then moving either forward in time to classic shockers like Psycho and The Birds from the 1960s, or backward into his British masterworks of the 1930s such as The 39 Steps and The Lady Vanishes. Many, including myself, have a special fondness for his earliest films produced after Hitchcock’s arrival in Hollywood in 1940, including titles like Foreign Correspondent and Rebecca, recently announced by the Criterion Collection as due for a return to “in-print” status this coming September.

These earlier decades of Hitchcock’s work have been the specialized domain for Criterion to preserve and present in characteristically robust editions over the past few decades now. Those later titles have proven to be rather lucrative for the studios holding their rights, hence Criterion has never been able to release more than a few titles from Hitchcock’s post-WWII output – a laserdisc of 1959’s North by Northwest and DVDs of Spellbound (1945) and Notorious (1946), all currently OOP, though there is hope that the latter two may eventually follow Rebecca‘s path to seeing their spine numbers restored in new HD editions. It seems that the rights-holders are understandably reluctant to license out films that continue to generate a lot of interest (and revenue) from contemporary audiences due to the visual flair, the iconic moments and the unique blend of curiosity and nostalgia that his undisputed classics continue to generate among new generations of viewers.

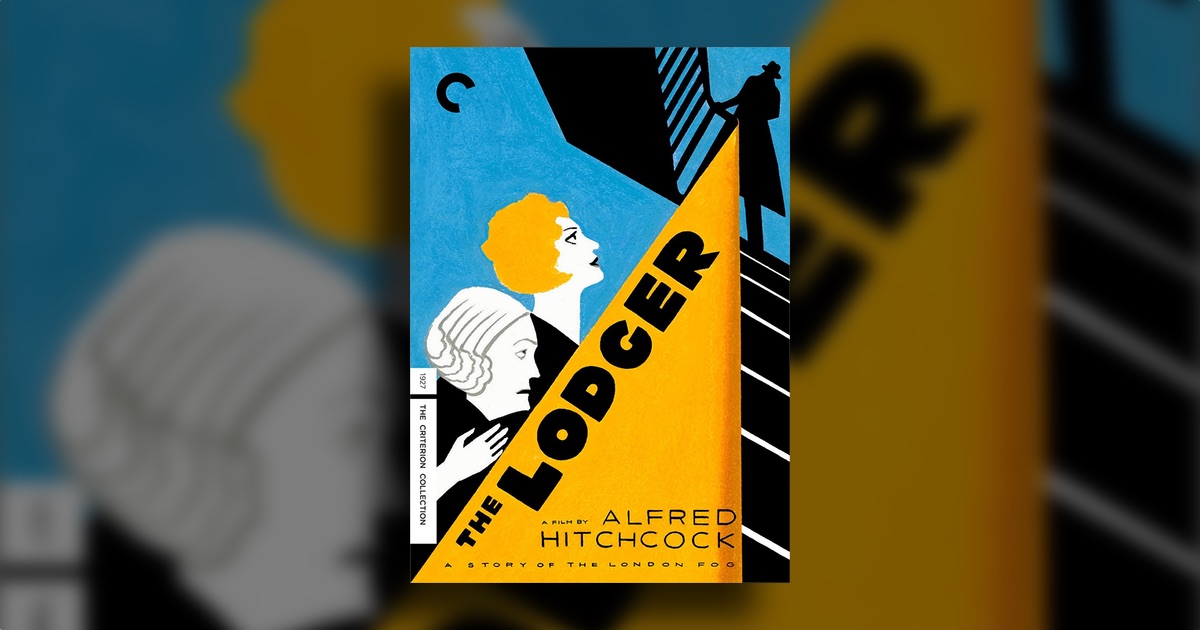

Given the luster of attraction that Hitchcock’s most famous productions have earned and rightfully deserve, it would’t be entirely unreasonable for relative novices to draw the conclusion that the director’s early films, shot on much lower budgets and stylistically primitive by comparison, are a substantial step down from the surefire combination of crowd-pleasing entertainment and bountiful food for thought they’ve come to expect. And I’m not here to argue that they would be wrong for thinking along that line. From where I sit, I can’t honestly make the case that The Lodger: A Story of the London Fog will deliver the goods as spectacularly as just about any Hitchcock offering one might care to name released from 1934 onward. But what I can say is that this new Blu-ray package is a vital and satisfying document in its own right, very worthy of the several hours of dedication required of us to become familiar with its contents. And for anyone who holds serious ambitions of gaining something close to a comprehensive sense of insight into what drove Hitchcock to make movies the way he did, I think it’s fair to say that this is an essential addition to the canon of texts that shed light on the man and his oeuvre.

The Lodger, which debuted in February 1927, is officially listed as Hitchcock’s third directorial effort, but we hear the man himself, in a 1962 interview with Francois Truffaut, acknowledging that in his opinion, it was his “first” picture, establishing so many of the themes and motifs that would characterize and unify his output over the next half-century. A prototype of the suspense-thriller genre, the story lures viewers in via the intrigue of investigating a series of murders targeting young blonde women, committed by a mysterious figure who calls himself “The Avenger.” A middle class family, living close to the London neighborhoods where the killings have taken place, offer a month’s lodging in their upstairs apartment to an enigmatic young man whose appearance and behaviors uncannily begin to match up with what little is known about The Avenger. Their realization instills a compelling sense of dread and anxiety in the hosts and the audience alike, especially after an embryonic romance develops between the strange visitor and Daisy, the couple’s charming but naive daughter, who just happens to be a pretty blonde herself. Viewers of the late 1920s, almost completely unaccustomed to the visual and narrative sleight of hand that Hitchcock grasped so cleverly even at the outset of his life’s work, found themselves extremely vulnerable to the director’s manipulations. As it turned out, they couldn’t get enough of this sort of thing, and they kept coming back for more.

The Lodger starred Ivor Novello, who was a huge British matinee idol of that era (he reminded me of Hugh Grant, from back in his 1990s prime), and went on to considerable commercial success, even though the film itself was not very well received by its producers when Hitchcock first delivered it up for their approval. It sat on the shelves for the latter half of 1926 and came perilously close to getting buried altogether, but Novello’s popularity and the desire to get some return on the investment led to a bit of reappraisal and a few minor changes that Hitchcock grudgingly went along with. Probably the biggest adjustment involved constructing a resolution of the plot that was less ambiguous than the director would have preferred, but even this small eruption of incidental friction between the creative visionary and his financiers serves as a fascinating foreshadowing of numerous other bump-ups that Hitchcock would have to work around with censors, production codes, agents, and studio bosses for many years to come.

Watching The Lodger in 2017, some 90 years after its theatrical debut, almost certainly won’t stir up the same kind of enthralled response that it did among its contemporaries. Critics of the time quickly christened it as “the finest British motion picture ever made,” but even if all accounting on behalf of The Lodger‘s historic significance were to tallied up as pure credit, I don’t think this film would register even among the top 50 entries in that nation’s cinematic output. For starters, it’s a silent film (if the 1927 release date didn’t instantly inform you of that) and is thus prone to some of the stilted mannerisms and melodramatic heavy-handedness that was the standard of the day in that era. Furthermore, British cinema was at such an embryonic stage of development that it’s almost not fair to compare any English film from the 1920s to the glories yet to come. Still, it’s an important milestone on several fronts and is very much worthy of the attention that Criterion lavishes upon it. We get a beautiful 2K restoration of the image in all of its original sepia-tinted glory, a brand new and brilliant orchestral score (not just the usual solo piano accompaniment) that is wonderfully effective at luring viewers into the emotional undercurrents running through the narrative, and an excellent array of insightful supplements (new and archival interviews and a visual essay) that draw our attention to details of production, themes and narrative structures that we might miss in our first pass through these quaint old movies.

Oh, did I say “movies” – as in plural? Yes I did, and that’s because this edition of The Lodger contains a top-quality restoration of Hitchcock’s fourth (or should we say, “second”?) film, Downhill, also starring Ivor Novello. The accompanying feature runs about a half-hour longer than the main attraction, but feels considerably longer and doesn’t deliver anywhere near as many thrills, even if The Lodger‘s thrills themselves might seem predictably telegraphed by today’s (or Hitchcock’s subsequent) standards. Downhill is a bit of a morality play, about a virtuous English schoolboy whose misplaced vow of loyalty and honor to a classmate chum leads to a precipitous fall from grace with his aristocratic family and a dismal slide into ruin among the dregs of society in Paris and Marseilles. Based on a script by Novello and his collaborative partner Constance Collier, who wrote under a pseudonym, the story slogs along at times as it ruminates on the sad fate of the unfortunate boy, whose misery seems to have been easily enough avoided if he had just spoken up a bit more assertively on his own behalf. But Hitchcock does get ample opportunity to construct several very nicely shot scenes, culminating most memorably in a “delirium” sequence toward the end that does at least provide a nice payoff for the time it takes to get there, and is worthy of a few replays from the Chapter Menu for future reference.

Topping off the package is a tidy half-hour radio adaptation of The Lodger from 1940, directed for the airwaves by Hitchcock himself after he had relocated to the USA. I know that not everyone takes the time or gets much from listening to these old relics that Criterion occasionally includes in their editions of films from this era, but I think this is one worth checking out, if only because it bears Hitch’s imprimatur and reveals a new audio-only interpretation of material that Hitchcock first presented at a time when dialogue and sound effects were not an option. His apparent desire to revisit such seminal material and place it in a new context indicates the value that Hitchcock placed on The Lodger as a reference point of ongoing and enduring importance to fully understanding his work. Criterion has done us all an immense favor by lifting these two films out of the public domain quagmire and placing them into what will be regarded as a definitive showcase for the earliest phase of Alfred Hitchcock’s superb contributions to the cinematic arts.

![Bergman Island (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/bergman-island-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/this-is-not-a-burial-its-a-resurrection-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![Lars von Trier's Europe Trilogy (The Criterion Collection) [The Element of Crime/Epidemic/Europa] [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/lars-von-triers-europe-trilogy-the-criterion-collection-the-element-of-400x496.jpg)

![Imitation of Life (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/imitation-of-life-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (The Criterion Collection) [4K UHD]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/the-adventures-of-baron-munchausen-the-criterion-collection-4k-uhd-400x496.jpg)

![Cooley High [Criterion Collection] [Blu-ray] [1975]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/cooley-high-criterion-collection-blu-ray-1975-400x496.jpg)