Week after week, month after month, the Criterion Collection routinely publishes definitive, affordable editions of some of the finest films ever made. They do so with such regularity that it’s easy to take it all for granted, as if it’s simply inevitable that we should enjoy the privilege of taking these cinematic treasures into our own possession, for convenient viewing whenever the urge to revisit them may strike. Whether it’s a new pop sensation like Frances Ha, a venerable classic like City Lights, or a massive serial of genre films like the Zatoichi box set, Criterion covers their turf with impeccable taste and style. Still, there are times when I think it’s necessary to just step back from the on-rushing stream of greatness and express simple gratitude and amazement for the excellent work they do. Such are my sentiments at the moment as I pause to consider the impact that Criterion’s newly refurbished edition of Tokyo Story has had on me. It’s not every day that we see a #3 film on the Sight and Sound list of all-time greatest films get a new and definitive release. Since Criterion won’t be getting rights to either Vertigo (#1) or Citizen Kane (#2) in the foreseeable future, this lends Tokyo Story a special kind of prestige that deserves a unique moment of recognition and celebration.

Before I get into the distinctive attributes that commend the new release of this film to any serious collector of the world’s greatest films, I’ll offer a few thoughts on what Ozu’s masterpiece conveys to me in 2013. Watching it again and immersing myself in the film over these past few days, I’m struck by just how it overflows with so many of life’s smaller, transitory details. The plot trajectory of strained family dynamics, put to the test when elderly parents visit their busy, preoccupied offspring in the midst of their ordinary working class lives, is familiar enough to most readers that I won’t bother recapping it here (and for those who are new to the film, my 2010 review, linked below, digs deeper into the film itself than I intend to in this essay.) But even if one were to set all that aside in order to focus on the grace notes and fleeting moments, there’s so much to take in… the barbed repartee between controlling parent and headstrong child… the drunken reminiscing of suddenly, unexpectedly reunited old friends… the petty conflicts and internecine power struggles that take place in various types of work setttings… the smug rationalizations that we all engage in to sidestep the avoidance of responsibility so that we can pursue our own selfish agendas… the painful awkwardness of funeral gatherings and other forms of family reunion… Ozu and his co-writer Kogo Noda have a direct and piercing insight into these and so many other routine human behaviors, making Tokyo Story a useful tool for advanced studies in the psychological mechanics of everyday life. Of course, this is just an introductory text; Ozu’s entire surviving oeuvre rounds out the picture quite thoroughly. But I understand that for many viewers, Tokyo Story represents a point of entry into Ozu’s world, one in which I feel comfortably assimilated now, to the point where I have to press myself a bit to recall just how unique and alien his filmmaking style seemed to me upon first encounter so many years ago.

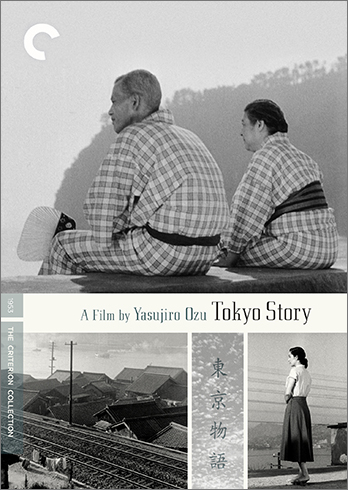

Ever since I reviewed the film back in 2010, I’ve been eagerly awaiting the day that a cleaned-up restoration of Tokyo Story could be added to my library. While the 2003 Criterion DVD was undoubtedly sufficient to introduce many of us to what the critical consensus has anointed as Yasujiro Ozu’s single greatest film, it’s been clear for quite a few years that something better was needed, if only to acknowledge its status as a pinnacle achievement of world cinema. For starters, the cover art offered a poor representation of the movie we saw on our screens. Ozu never worked in the kind of extreme close-up we see in the graphics on the old release, which features Setsuko Hara’s left eye shedding a sad, singular tear on the cover and Chishu Ryu’s right temple on the insert flyer. Nor is the cinematography ever as dark and ominous as that charcoal-grey cover might lead us to expect. In this new edition, art director Sarah Habibi and designer F. Ron Miller have much more effectively captured the essence of Tokyo Story with a simple, tactful collage of iconic images drawn directly from the film, on the outer slipcase as well as the interior digipak and accompanying booklet. Each of the more than two dozen stills included in the packaging summon immediate thoughts and feelings from those who have already seen and digested the film, making the simple act of holding the case and examining its contents a significant moment of recollection and contemplation.

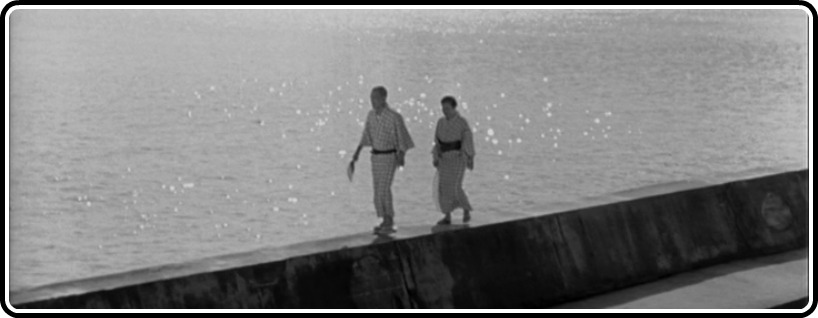

Of course, an improved box and inner sleeve don’t amount to much if the transfer quality of the film itself disappoints, but I’m happy to report that we’re blessed with a substantial improvement in that department as well. The digital clean-up and restoration is extensive enough to provide viewers with a minimum of distractions as far as overtly damaged frames are concerned, but not so excessively processed as to erase all traces of the roughness and grit that seems appropriate to an Ozu film from this time. In short, this version of Tokyo Story is something a bit less than pristine, which is exactly as it should be. The musical interludes and dialogue of the mono soundtrack come through with clarity, with just a touch of the warble and scraping that original audiences no doubt experienced when they watched it in theater. At the heart of it all is a highly welcome visual stability that presumably provides as ideal a viewing experience as we have any right to expect. Even if you are one of those viewers still watching these films in the DVD format, I can attest that the upgrade is worthwhile after comparing my 2003 and 2013 versions side by side on the same monitor (and you’ll have the convenience of that blu-ray ready and waiting whenever you get around to updating your home theater system.)

The final, most tangible benefit to getting ahold of this new edition is the addition of a supplemental feature that wasn’t already included on the release from ten years ago. It’s a 45 minute documentary titled quite plaintively Chishu Ryu and Shochiku’s Ofuna Studio. The main focus is the venerable actor Chishu Ryu who features prominently in Tokyo Story and the bulk of Ozu films released before and afterward. It’s the only bonus clip that wasn’t originally included in the old double-DVD edition, and a nice recap of one of Japanese cinema’s most distinguished acting careers, as well as a fascinating glimpse at the inner workings of Shochiku Studios as it went through a modernization process in the late 1980s. Ryu outlived Ozu by another three decades and continued his acting career almost up through the end of his life, in sharp contrast to his most famous co-star Setsuko Hara, an era-defining superstar in Japan who retired from the screen almost simultaneously to Ozu’s passing at age 60 in 1963. Hara is still alive at age 93 as of this writing, a thought that makes me happy, even though she hasn’t made any public appearances over the past fifty years. Her reputation remains gladly and deservedly cloaked in the mystery of an eternally preserved youth that transitioned into a dignified maturity in her later films, before she reclaimed her right to privacy and anonymity once more.

In addition to the Chishu Ryu essay, a tribute to Ozu featuring numerous directors whose works have been picked up by Criterion (Wim Wenders, Claire Denis, Lindsay Anderson, Aki Kaurismaki, among others) and a fairly comprehensive biographical compendium on Ozu’s life titled (after the style of several early Ozu films) I Lived But… make this package an ideal entry point for any who are new to the director’s work and curious to discover what makes him so great. This short clip of Donald Ritchie offering his perspective on Tokyo Story from I Lived But… was recently featured in the Criterion Current:

I’ve offered the opinion on several occasions that a better approach to working one’s way through Ozu would be to start with the Silent Ozu Eclipse Series set and just work forward through A Story of Floating Weeds, the double-disc The Only Son/There Was A Father box, then on to the postwar classics Late Spring and Early Summer and from there, Tokyo Story and the Late Ozu Eclipse set (with Good Morning – now the most desperately-needed Ozu upgrade of all – and Floating Weeds inserted somewhere in the mix) and finishing off with his final film, An Autumn Afternoon. But given that my first exposure to Ozu came via Tokyo Story, owing entirely to its towering critical reputation, I understand that a lot of viewers will start their journey at this particular point of reference. Criterion knows that even better than I do, and I commend them for making this dual-format release of Tokyo Story a very attractive, comprehensive and authoritative overview of a great master’s body of work. With the Thanksgiving holiday (and all its attendant bargains) just in front of us, and some thoroughly wonderful additions to our home video libraries enticingly within reach, this is one that belongs near the top of any self-respecting cinephile’s wishlist.

![Bergman Island (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/bergman-island-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/this-is-not-a-burial-its-a-resurrection-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![Lars von Trier's Europe Trilogy (The Criterion Collection) [The Element of Crime/Epidemic/Europa] [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/lars-von-triers-europe-trilogy-the-criterion-collection-the-element-of-400x496.jpg)

![Imitation of Life (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/imitation-of-life-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (The Criterion Collection) [4K UHD]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/the-adventures-of-baron-munchausen-the-criterion-collection-4k-uhd-400x496.jpg)

![Cooley High [Criterion Collection] [Blu-ray] [1975]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/cooley-high-criterion-collection-blu-ray-1975-400x496.jpg)