Upon its 1971 release, Sam Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs obviously offended Roger Ebert, who issued a scathing review. Where he found purpose and even poetry in the grisly violence of Peckinpah’s prior film The Wild Bunch, when Peckinpah translated that western violence to a bucolic English village and, more uncomfortably, into the domestic sphere, Ebert drew the line: “Peckinpah’s theories about violence seem to have regressed to a sort of 19th-Century mixture of Kipling and machismo.” Straw Dogs offended many on its release and continues to offend nearly fifty years since, though it has also become a well-regarded, confrontational classic. Even Ebert, in 2011, admitted that “something within me has shifted,” and recognized “how close to home the movie strikes.”

Is this film offensive? Yes! Is it a rich masterpiece worthy of our prolonged estimation, and perhaps even our esteem? Yes! We should be offended by much of what happens and why and how, and we should even perhaps be offended at Peckinpah’s audacity and evident misanthropy, but all of that’s to the film’s credit. Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs is uncomfortably and unabashedly direct in its violence, whether it’s psychological, sexual, or the gory kind that comes with guns and fire pokers. But there is a deep, and to me genuine and honest, exploration of the insecurities and social structures that engender violence, even within the passive hearts of people who wouldn’t hurt a fly or dream of picking up a weapon.

The story begins when the Sumners, a young couple, show up in a small English village. The husband, David, played by Dustin Hoffman, is an American mathematician. He and his English wife, Amy, played by Susan George, have decided to situate themselves in an old family home an old village in Cornwall where she grew up, hoping that the complete change of pace will help David focus on his important book.

We first meet them as they show up in the village, Amy wearing a turtle neck but, obviously, no bra. This is an early place where one can get offended. Peckinpah lingers on Amy’s features, the camera obviously standing in for the many men in the village who are lingering on Amy’s features, too. She knows most of these men, and they’re delighted to see her return, but mostly because she’s gorgeous, perhaps displaying features they’d never seen her display before she left and matured in America.

If the camera stands in for these men, it also stands in for men in the audience who are admiring what they see, and who may love to get closer to this beautiful woman. This is also granted vicariously. Amy’s old boyfriend, Charlie, comes over and freely fondles Amy. What do we think of what we are seeing now? And, as important, who do we blame for Charlie’s behavior? Do we think Amy had a responsibility to dress more modestly, to avoid this unwanted advance? David has gone into the bar for some cigarettes — anything American, he announces while all of the locals listen — but he can see from the window that David is assaulting his wife, groping her as he must have done countless times before. Whose he blaming?

David is offended, naturally. He’s an insecure, possessive man who feels progressive but who also considers his smart, beautiful wife to be his property. He wants to show off his property, but he wants his property to consider the consequences her own showing off might bring (he later tells her she should consider being a bit more modest). Amy takes care of herself with Charlie, though, and an uncomfortable David returns to the vehicle feigning ignorance and pleasantries. We see that David is not naturally prone to defending himself with direct confrontation. He even asks Charlie if he’ll come help some others work on his dilapidated barn roof.

Charlie, and the other men who work for David — importantly, they are working for David, receiving money to do manual labor on David’s property — recognize David’s propensity for passivity. Though David is smart enough to know what their chuckles mean when he’s walking away from them, they’re fine working him up. Up close and personal, they still call him “sir,” and he acts like the pleasant benefactor; underneath, though, simmers a battle of male egos (and, under that, super-ego and id). David may feel superior, but he cannot handle that they might think their conventional manliness actually puts them in a superior position.

Amy recognizes David’s passivity too, of course. When the men ogle her and mock David, she expects him to stand up and “be a man.” If she was attracted to his intellectual pursuits in America — was she one of his enamored students? — she has different expectations here among these men.

The film moves on, tensely. The simmer becoming slowly more violent. One day, surprisingly, they find their cat hanging in their bedroom closet. This is the first act of physical violence — after plenty of psychological violence, enacted by all — and Amy calls into question David’s control over his own domain: this act was to prove, she says, that they could get into his bedroom (not “our” bedroom).

Is she taunting him?

Yes, she is. And she’s also hoping he might be the husband she wants him to be. By this point in the film, we recognize that David and Amy do not particularly like or respect each other. They keep up pretenses, utilizing their youth and sexuality to maintain a semblance of marital bliss, but that is it. He thinks she’s beneath him. She recognizes this and also recognizes her power over him.

‘You’re a coward,” she says, to which he immediately responds, “No, I’m not.” Ignoring him, she goes on: “And I’m a coward.” Rather than reassure her there, he simply says again, “I’m not.” Of course he’s deluding himself. He says both phrases quietly, as if mostly to himself. Eventually, rather than confront the cruel men who are upsetting his wife, he decides to show them he’s not affected by agreeing to go shooting with them. He thinks that this will show they have no power over him, that he’s brave, and that he can do conventionally manly things. This route also avoids conflict.

But rather than help David assert his position among these men, his shooting trip turns into one of the most controversial scenes in mainstream Hollywood history. While out on this shooting trip, Charlie abandons the group, goes to the Sumner home, and rapes Amy. She resists for a while, but then she seems to relent. She even seems to start enjoying it. Entering the intimate scene with a shotgun pointed at Charlie, one of the other men wordlessly demands his turn. Whatever Charlie’s affection for Amy is, he begrudgingly helps the man; after all, the man has a gun. This time, Amy never shows signs of enjoyment, screaming the whole time.

Without going into the bloody ending of the film, I think we can already ask ourselves questions about the role, the uses, and the detriments of violence in our lives. Some condemn the scene and the film saying this scene suggests this particular kind of violence is good for the victim: she may say no, but she actually wants it and eventually will relent and enjoy it. This is fair criticism. Such a perspective on rape is abhorrent and deserves absolute condemnation.

But the film itself, which portrays this situation, still deserves our forbearance of immediate and absolute condemnation because this scene is so much more complicated. Though no one should walk away thinking Charlie did right, it’s important to recognize Amy’s own emotional struggles leading to this point. She has wed a man she now considers weak and whom she deeply disrespects, even if she sometimes has fun with him. She does resist Charlie, an old lover, for a time, but there are many reasons someone in her situation would do exactly what she does — which is stop struggling, apparently enjoying it.

Furthermore, the subsequent rape — following the heals of the first almost immediately — is by no means pleasurable to her. She does not give in, she does not enjoy, she does not forgive, she does not think this will give her husband what he deserves. To me, this undercuts any criticism that the film is suggesting violence is good for the victim.

Undercuts, I say; not abolishes. It’s all deeply disturbing, troubling to see any of this depicted on screen, but it’s there and I don’t believe we serve ourselves or our culture by looking away.

The film continues onward, Amy suffering from the psychological effects of these rapes, Amy not trusting that she can confide in her husband. And, as I’ve alluded to and as is probably well known, the film goes to another dark (though, to me, not darker than the rapes) place when David and Amy turn to violence to protect their home. The underlying conflicts between many of the characters — engendered by jealousy, machismo, lust, insecurity, etc. — come to the surface in a blood bath when those left standing (few) look around, surprised at what they were capable of.

It’s an ending that’s ripe for criticism. Is it only through violence that David’s able to become a better person? Did he need to prove to himself and to Amy that he could, when pushed, not only defend but prevail?

The film is, thankfully, ambiguous. David himself probably feels like the answer, at this moment, is yes. But we can wonder, is he really a better person at the end?

It’s these complexities and ambiguities and Peckinpah’s (and his actors’) willingness to go there that makes Straw Dog importantly provocative, and not just provocative for kicks. So, essentially, I think Roger Ebert was right to be offended in 1971 and right to reconsider in 2011. It’s worth the decades of contemplation.

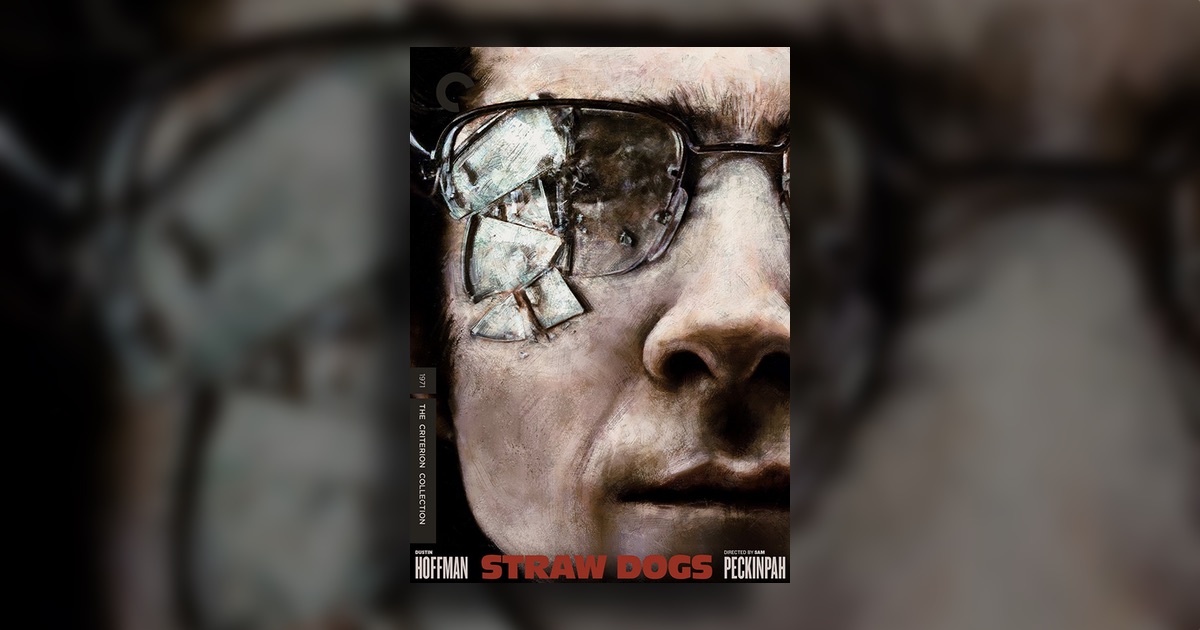

The newly released Criterion edition, which brings this title back in print after years and years of out of print status, contends with the difficulties of this film well. Stephen Price’s old commentary from the original DVD is an exceptional defense of the film that does not ignore its problems. Susan George talks in an interview about the love/hate relationship she had with Peckinpah, though she is very proud of her work in Straw Dogs. And, among others, is a feature new to this edition: a frank and open interview with UC Berkley Film professor Linda Williams, in which she looks at the problematic role of sex and violence in cinema, and in particular Straw Dogs, with a great analysis of the film and its importance to getting us to confront these uncomfortable aspects of our culture and society, even if she ultimately feels Straw Dogs is on the wrong side of history.

All in all, this is an important edition for such a complicated film. The new 4K restoration has resulted in a gorgeous presentation of the film itself, and the supplements ensure that it’s not so easily imbibed or dismissed.

[amazon_link asins=’B06XP5R1MS,B06XNW5SJ4′ template=’ProductCarousel’ store=’criter-20′ marketplace=’US’ link_id=’673c54ad-5b8e-11e7-ad26-3b2925cb4f96′]

![Bergman Island (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/bergman-island-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/this-is-not-a-burial-its-a-resurrection-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![Lars von Trier's Europe Trilogy (The Criterion Collection) [The Element of Crime/Epidemic/Europa] [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/lars-von-triers-europe-trilogy-the-criterion-collection-the-element-of-400x496.jpg)

![Imitation of Life (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/imitation-of-life-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (The Criterion Collection) [4K UHD]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/the-adventures-of-baron-munchausen-the-criterion-collection-4k-uhd-400x496.jpg)

![Cooley High [Criterion Collection] [Blu-ray] [1975]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/cooley-high-criterion-collection-blu-ray-1975-400x496.jpg)