When Spalding Gray died somewhere around January 2004, he left behind a body of work unique in American theater: a series of monologues that broke new ground in performance, monologues that told the story of various aspects of Gray’s life, monologues that he performed sitting alone at an unadorned wooden desk with a spiral notebook, a microphone, and a glass of water. Despite the minimalist nature of their setting, these monologues invariably never failed to delight and charm audiences, and this is entirely due to Gray’s ability to be self-effacing, revelatory and riveting; they felt like conversations with an old chum that could have you on the edge of your seat one moment, and falling off it from laughter the next.

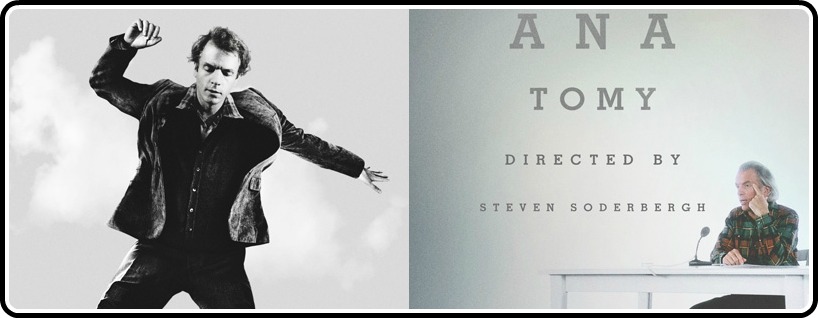

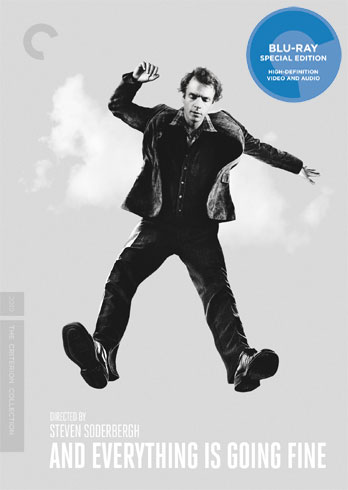

When Spalding Gray died somewhere around January 2004, he also left behind a family consisting of a wife, two young sons, and a stepdaughter. He is believed to have committed suicide by jumping off the Staten Island Ferry, although no one is entirely certain about that, or the exact date of his death. (His body was found and pulled out of the East River two months later.) While he had been dealing with depression and various neuroses throughout his life — more than a few of which are documented in his work — it worsened considerably after a 2001 car accident in Ireland that left him with a permanent limp and a metal plate in his head; there is speculation that there was brain damage as well, which may have exacerbated the obsessive thoughts about death and suicide he had entertained since his mother’s suicide in 1967. “The new fear was not only that Mom had killed herself, but had also laid the groundwork to kill me,” Gray wrote, according to the essay contained in the booklet that accompanies And Everything Is Going Fine, the 2010 documentary about his life directed by Steven Soderbergh. This is one of two Soderbergh films about Spalding Gray that are newly released from the Criterion Collection, the other being 1997’s Gray’s Anatomy; neither of these films plumb the depths of despair that its subject felt throughout his life — something that is explored in much greater detail in The Journals Of Spalding Gray, edited by Nell Casey — but perhaps that is for the best, for it is a more enjoyable experience to remember Gray as we knew him from his performances. (One can only hope that Criterion also manages to acquire King Of The Hill, the 1993 Soderbergh film which was also his first collaboration with Gray. It’s a great and sadly overlooked film that has never been released on DVD, although it has recently become available for streaming via Netflix.)

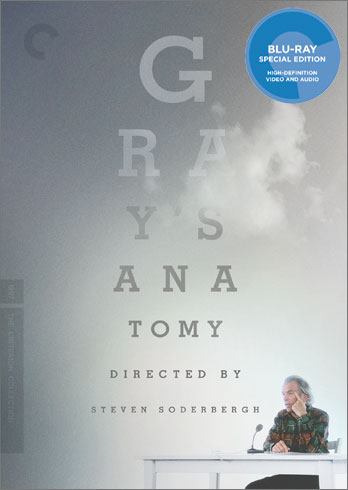

Gray’s Anatomy is a filmed monologue, and the third of his theatrically released monologues. 1987’s Swimming To Cambodia, directed by Jonathan Demme, put him on the map, and its simple visual style recalls Demme’s work on the seminal Talking Heads concert film Stop Making Sense. In 1991’s Monster In A Box, filmmaker Nick Broomfield took a more expansive approach, with more camera movement and dramatic lighting effects, but it was still essentially a guy at a desk. Steven Soderbergh explodes the stage-bound concept and takes the viewer on a sometimes startling visual journey, following Gray as he narrates his story about his attempts to deal with an eye condition via any means other than surgery, including a sweat lodge and a visit to “the Elvis Presley of psychic surgeons”. You heard me. Along the way, backgrounds change, scenery flies in and out of the frame, and Gray’s desk — not to mention Gray himself — is moved across the floor, almost always amid a riot of lighting changes and music from Soderbergh’s longtime collaborator Cliff Martinez.

To see Gray physically separated from his desk, at least momentarily, is a sight that at once baffles and delights: it is as though Soderbergh is stripping the knight of his armor, or pulling the net out from under the tightrope walker, and one cannot help but wonder how much further the director could have taken Gray in that direction had they collaborated on another picture.

The story itself is always entertaining but might prove uncomfortable to viewers sensitive about their eyes (like me!) as Gray speaks in detail about the nature of his condition; not helping matters in the least is another Soderbergh innovation in which several people seemingly unconnected to the story tell their own tales of terrible things happening to their peepers, such as accidentally squirting crazy glue into them, or finding a piece of wire stuck in them after an industrial mishap. (Seriously, when I saw this film in its theatrical release, I nearly fainted from some of this stuff.) These folks stick around and become a sort of Greek chorus, commenting on the occasionally ridiculous nature of some of Gray’s attempts to avoid traditional medicine, which may have been rooted in his mother’s Christian Science beliefs, if not plain old denial. Soderbergh manages to keep all these balls in the air and still bring it in for a landing in a tight 79 minutes; the Criterion blu-ray features an outstanding high-def transfer of the film, with picture and sound far superior to the old Fox Lorber DVD.

Lest anyone think they’re getting short-changed by such a brief film, there are several bonus features, starting with an entire second monologue: in A Personal History Of The American Theater, Gray spends an hour and a half taking the audience through recollections of the roles he played in his stage career. It’s an old videotaped performance, so the quality is less than stellar, and the monologue itself is a bit uneven, but some of the stories he tells are a hoot. There is also an interview with Soderbergh and Renee Shafransky, with whom he had a long relationship that included collaborating on many of his monologues. As if all that ghastly talk about eye disasters wasn’t enough, a sixteen-minute video of Gray’s eye surgery entitled Swimming To The Macula is thrown in — I’m not gonna lie to you, I fast-forwarded through that one. Finally, a trailer is included, and a booklet containing an essay by critic Amy Taubin.

And Everything Is Going Fine is a unique documentary record of its subject in that no effort is made to explain to viewers just who the heck Spalding Gray is — you’re just thrown into the deep end (a perverse metaphor to employ given his fate, but I regret nothing) as he tells the story of his life through a variety of mostly videotaped interviews, monologues, photographs and home movies.

In the accompanying booklet, Soderbergh explains, “‘¦There is no attempt to contextualize this for people who don’t know who he is. It’s not for the uninitiated,” but even those with little or no familiarity with Gray’s work can still be entertained simply because this is Gray doing what he has always done best — talking about himself. As the film takes us through his life up to his final days, one can see at the end just how much his accident robbed him of his spirit, and what happened after (which is not explored in the film) seems only that much more tragically inevitable.

Due to the quality of much of the videotaped footage in And Everything Is Going Fine, the picture and sound of the Criterion blu-ray are nothing to shout about, but it’s far from terrible, and more or less deliberate on the part of the director. Like Gray’s Anatomy, this disc’s bonus features include another monologue, in this case his first, Sex And Death To The Age 14; it’s another videotaped performance dating back to the ’80s, and while it’s better than A Personal History Of The American Theater it still doesn’t compare to his superior later work.

Also included is a making-of featuring Soderbergh, his editor Susan Littenberg, and producer Kathleen Russo, with whom Gray also collaborated and to whom he was married at the time of his death. There is also a trailer, NO gross eye surgery videos, and the aforementioned booklet with an essay by Nell Casey, the editor of Gray’s published journals. (His journals, incidentally, do give a more detailed picture of the man but, as so many bios seem to nowadays, it also presents a far more unflattering personality than his other works would suggest. The worst thing I found in it: he didn’t like Bunuel’s The Exterminating Angel! What’s the matter with that guy?)

Despite (or maybe because of) the darkness of his journals, it is the filmed Spalding Gray that I prefer to remember, the sweetly vulnerable neurotic in his flannel shirts, the New England WASPy Woody Allen using a desk for a shield, the teller of tall tales and less-than-ripping yarns that involved no espionage, swashbuckling or feats of derring-do, but a deceptively average guy trying to make sense of his screwy life.

That’s the Spalding Gray that will make you laugh, make you think, make you wince. That’s the Spalding Gray who can conjure up whole worlds out of a spiral notebook and a glass of water. That’s the Spalding Gray who, despite the insurmountable hurdles he faced in his own life, used his art to make life a little better for the rest of us.

And so, that’s Spalding Gray.

![Bergman Island (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/bergman-island-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/this-is-not-a-burial-its-a-resurrection-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![Lars von Trier's Europe Trilogy (The Criterion Collection) [The Element of Crime/Epidemic/Europa] [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/lars-von-triers-europe-trilogy-the-criterion-collection-the-element-of-400x496.jpg)

![Imitation of Life (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/imitation-of-life-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (The Criterion Collection) [4K UHD]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/the-adventures-of-baron-munchausen-the-criterion-collection-4k-uhd-400x496.jpg)

![Cooley High [Criterion Collection] [Blu-ray] [1975]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/cooley-high-criterion-collection-blu-ray-1975-400x496.jpg)