I am unreservedly ashamed to admit I have never seen a Jafar Panahi film. The seminal Iranian filmmaker, whose work which includes Crimson Gold, The Circle and Offside, is familiar to me in name only. But you do not have to have seen anything by Panahi to feel the staggering act of defiance that this non-film represents.

It also serves as a treatise on the stifling state of Iranian cinema where talent is certainly in abundance (case in point; A Separation, the first Iranian film to win the Foreign Language Oscar). The Culture Ministry’s recent decision to disband the House of Cinema, the only domestic independent film organization, has been a critical obstruction to the already censorship-ridden national cinema. Painstakingly constructed subversiveness is no longer an option for Jafar Panahi. The 51-year old Iranian filmmaker has been handed a 6-year jail sentence and a 20-year ban on filmmaking, leaving the country or giving press interviews of any kind.

This Is Not a Film, shot by Panahi’s documentarian friend Mojtaba Mirtahmasb, seemingly takes place over one day, although it was shot and edited over ten days. Panahi and Mirtahmasb clearly have some idea of what they wanted to be contained within, although how much of that was discussed we do not know.

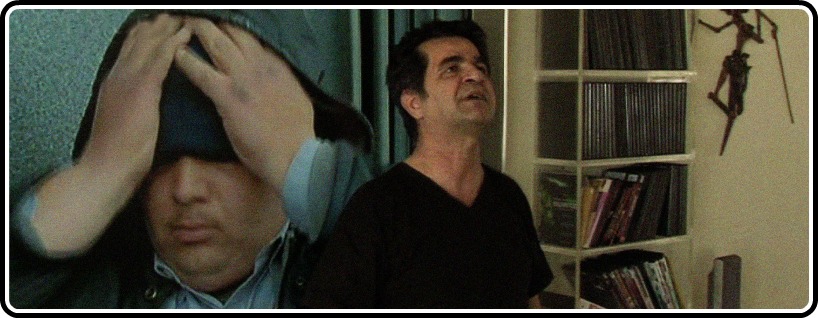

The finished self-described ‘˜effort’ shows Mirtahmasb coming over to film Panahi, who is under house arrest and has been waiting for the verdict from the court appeal of his sentence. Mirtahmasb expresses how important it is to document Panahi’s struggle. Mirtahmasb’s presence slyly exonerates Panahi from formally directing. If he is merely in front of the camera, in his natural state, he is breaking none of the bans placed on him.

There is a structure to This Is Not a Film. We start with Panahi and the camera, which Mirtahmasb left with him and told him to keep on. He eats his breakfast seeming somewhat awkwardly aware of the camera’s presence. He speaks with his lawyer on the phone. Then Mirtahmasb comes over. Neither knows what the end goal of this ban-dodging experiment is or should be. This uncertainty is what lends the non-film its structure.

Panahi’s thought-process launches an intellectual and emotional journey beset with rumination. He spends much of the film working through his recent rejected screenplay, trying his best, with descriptive mise-en-scene and masking tape, to paint any semblance of the picture he meant to one day create. To see this is to see an artist at work; it is heartbreaking to witness the man’s crystal-clear filmic map merely described, and his and our simultaneous understanding that it will never come to life.

Describing the story and its blocking does bring it to a sort of half-life in this film, and its seemingly meek half-existence is a courageous statement within the larger courageous statement that is this ‘˜film’. Panahi eventually stops, overcome by the apparent pointlessness of trying to create something in an unnatural fashion. He goes through clips of a couple of his previous films, frustrated by what actual production brings and what he no longer can do through paltry reenactments. He wistfully speaks of the unpredictable nature of working with actors, how the act of filming captures something that cannot be planned, blocked or staged. Showing clips from his previous films incorporate his works into a new artistic context, and is another way Panahi exercises as much control as he can over a situation he has no control of.

We see Panahi taking pictures and videos with his iPhone (because surely he can make use of the phone’s video features), on the day of Fireworks Wednesday, signifying the Persian New Year’s. He ponders aloud, goes online where most websites are restricted, watches the news, and looks outside. A neighbor comes by and asks him to temporarily watch her yelping dog Micky. His companion throughout is his pet iguana Igi who languidly slurps around.

There is constant fascination by the film’s very existence and its contents. At times it became surreal that I was actually sitting in a theater and seeing this complete with trailers and ads. Hell, there was even a spot for the new ABC Family show ‘Bunheads’ before the film started. That this made its way into a theater that was accessible to me and everyone in the surrounding area goes beyond words.

Throughout, the sense of restlessness that we can only imagine he experiences minute-by-minute is forced upon us. There is also a simultaneous transmission of suffocation. We cannot imagine what he is going through, but this effort gives us a sad and bitter taste of his claustrophobic experience. Is it a coincidence that Buried, the story of a man helplessly and powerlessly encased in the ground, is the most visible DVD on display?

The immediate affinity that we feel for Panahi somehow heightens this already heartbreaking human rights issue. He comes off as kind, mild, realistic and emotionally beaten down by his circumstances (though this work’s existence proves him as anything but). We immediately care for him, beyond the empathy inherent in the situation.

The spontaneous final scene and image is something to behold. I will let you discover it on your own.

There is so much to think about and unpack in This Is Not a Film, and hopefully these initial thoughts do some basic pondering. This may be the last participating effort from a director whose voice has been irrevocably muffled. It represents the concrete fact of creative expression being snuffed out. To say this film should be seen is an understatement; it must be seen. This statement has been made many times in relation to this film but I make it again; if you care about cinema, about the right we have to tell stories and why we tell them, and about human rights, you must seek out This Is Not a Film.

![Bergman Island (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/bergman-island-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/this-is-not-a-burial-its-a-resurrection-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![Lars von Trier's Europe Trilogy (The Criterion Collection) [The Element of Crime/Epidemic/Europa] [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/lars-von-triers-europe-trilogy-the-criterion-collection-the-element-of-400x496.jpg)

![Imitation of Life (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/imitation-of-life-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (The Criterion Collection) [4K UHD]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/the-adventures-of-baron-munchausen-the-criterion-collection-4k-uhd-400x496.jpg)

![Cooley High [Criterion Collection] [Blu-ray] [1975]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/cooley-high-criterion-collection-blu-ray-1975-400x496.jpg)