Biographical documentaries always present an inherent problem; how does one sum up a person’s life in ninety minutes? Some films take an event-heavy approach; we get a sense of the subject by accounting for the major events in their life and how they felt and acted in these moments. Other documentaries create a sort of snapshot of their subject. Bobby Fischer Against the World falls into a slightly different category.

This documentary examines Fischer’s psyche within the event-heavy approach using a cause-and-effect reasoning. Countless biographical documentaries fall into this category. The problem is that life, and people, are not this simple. On a gut level the documentaries that attempt this lofty goal are unsatisfying. Yet, many of these films are very good, and even great, because their goal may be futile, but the efforts and results are still revealing and informative. Bobby Fischer Against the World may not accurately account for Fischer’s entire life, but the reasons it suggests for his lifelong struggle and eventual paranoiac surrender are certainly food for thought, making for a harrowing and suspenseful portrait.

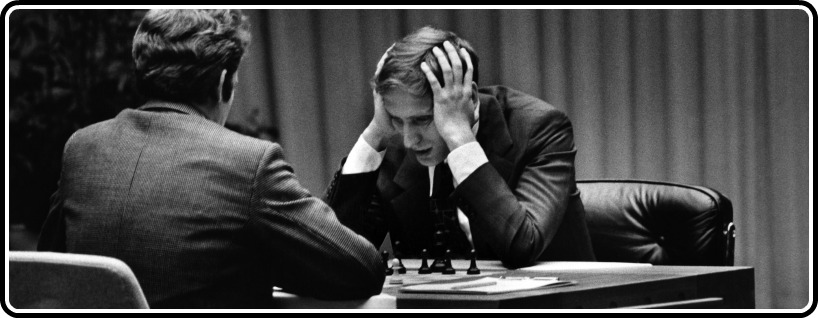

Over half of the film concentrates on the 1972 World Chess Championship between Fischer and Boris Spassky. It takes the time to impressively juggle many other facets such as Bobby’s childhood, his mother Regina, his obsessive nature and way the press depicted him. It also places chess in a broader context, looking at how the match was representative of the relentless competition between the U.S.A and the Soviet Union, transcending the game itself.

A variety of people are used for the talking heads. There are those who knew Fischer, such as Anthony Saidy and Harry Benson. There are those who are chess Grandmasters or U.S Champions. There are also Fischer biographers. Director Liz Garbus shoots the interview subjects within large scenic buildings and long hallways. This choice could have been off-putting, but they make for nice compositions because she keeps the background out-of-focus, retaining the mood of the setting but not the distraction of it.

Bobby Fischer sacrificed everything for chess and it led his ruin. The point this film drives home that hits the hardest is the idea that the elements of Fischer’s mind that accounted for his genius, were the same ones that drove him to a reclusive life of Anti-Semitic (he was Jewish) and Anti-American hate, filled with paranoid delusions and conspiracy theories.

His obsession with chess filled up all of his time. After winning the World Championship at twenty-nine; where does Fischer go from there? Where does anyone go from there? Surely he would defend his title; but he decides not to and forfeits. His stubbornness and obsessive nature allowed him to slide naturally into his reclusive life and represents the epitome of the dangers of truly living inside one’s own mind. To see one man’s drive be applied for something great, only to become a man with delusions of grandeur who fully welcomes such a horrific event as 9/11 is difficult to watch.

Bobby Fischer Against the World is tightly paced and suspenseful in its depiction of the World Championship. All of the interview subjects come into play during these segments, and together it creates a passionate display of how it all went down and what it meant for the game of chess and for the world at that time.

The way the press handled Bobby Fischer was to label him as ‘˜unusual’, ‘˜odd’ and ‘˜arrogant’. The film and its interviewees clearly take issue with this dismissive representation, but the film always stays on the same general level of the press. A lot of the statements made by the interviewees are sweeping and to a degree, speculative. There are a lot of things said in the film about Fischer, some good and some bad, but without having many examples, these statements can only be taken at face value. The footage with Saidy and Benson are the most revealing and their personal experiences with Fischer are incredibly valuable; there should have been a bit more of that.

The film makes a conscious decision not to go into Fischer’s reclusive years, only picking up in the early nineties when he resurfaced for a short while, and then in the early 2000’s when he is jailed. The effect of seeing a clean-cut Fischer in 1972 to a ragged looking homeless man twenty years later is nothing short of devastating to witness. However, by making no efforts to understand that time period in Fischer’s life, the film’s coverage is parallel to the press coverage of Fischer throughout his life. It never goes the extra mile that makes a truly great documentary as opposed to a sufficiently strong one.

His life is depicted as tragic; it is clearly film’s chosen angle amidst the Championship. Whether that is an accurate assessment is up for grabs and it seems to place no fault on Fischer who made conscious decisions that are, in all honesty, his doing. Yet it does an excellent job creating this angle. Citing other chess players with mental illness gives him essence of victim. So does his childhood complete with misidentified father and struggling but largely absentee mother. Bobby is self-taught while the Russians, including Spassky, were bred for chess-playing, receiving financial backing and proper training. That he did it all himself shows incomparable work ethic as well as willing sacrifice, always admirable qualities.

Biographical documentaries are reductive by nature, and while I use this film as an example of that, most of these films overcome this drawback in some way. This is not least because knowing they must be taken with a grain of salt allows one to sit back and appreciate what these films do give us. By telling a tight, suspenseful and difficult story, this film satisfies and does about as much as it can be expected to do in ninety minutes.

![Bergman Island (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/bergman-island-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/this-is-not-a-burial-its-a-resurrection-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![Lars von Trier's Europe Trilogy (The Criterion Collection) [The Element of Crime/Epidemic/Europa] [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/lars-von-triers-europe-trilogy-the-criterion-collection-the-element-of-400x496.jpg)

![Imitation of Life (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/imitation-of-life-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (The Criterion Collection) [4K UHD]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/the-adventures-of-baron-munchausen-the-criterion-collection-4k-uhd-400x496.jpg)

![Cooley High [Criterion Collection] [Blu-ray] [1975]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/cooley-high-criterion-collection-blu-ray-1975-400x496.jpg)

1 comment