Alain Resnais has made quite a mark on cinematic history since his breakthrough feature, Hiroshima mon amour, was released over fifty years ago, but aside from 1955’s Night and Fog, his career as a documentarian is much less widely-regarded. Between 1947 and 1959, he directed or co-directed over dozen short documentaries. Some simply observed artists at work in their studios, others challenged accepted attitudes towards past atrocities – Night and Fog is the most famous example, but his 1953 collaboration with Chris Marker, Statues Also Die, hit a little closer to home, showing how European consumerism has diluted the artistic merit of African art (the second half of the film was censored in France for a decade). Those who only know Resnais’s early work might see these as sharing the most commonalities with his narrative features; once you get to know Resnais as he is today, Le chant du styrène suddenly becomes a lot more revelatory.

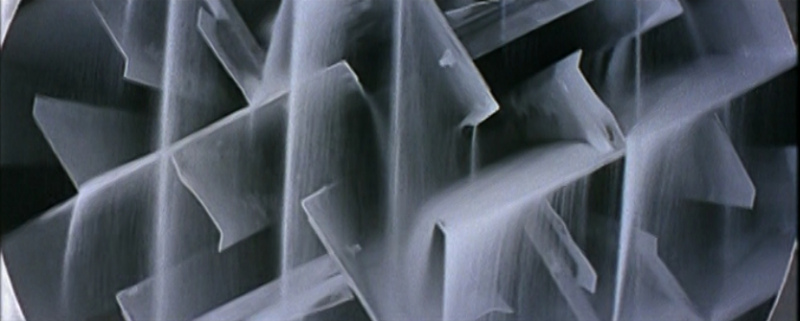

The film was commissioned by Péchiney, a French manufacturing giant that had long focused on aluminums (at one time, it was the 4th largest producer of such material in the world), but they commissioned this to speak to the wonders of plastics, and the essential organic compound required for their making. Resnais and cinematographer Sacha Vierny (who also shot Night and Fog, Hiroshima, and Last Year at Marienbad, among others, for Resnais) gaze with wonder, coasting along factory lines and sprinkling the frame with close-ups of intricate processes that turn into abstract art by virtue of the tight framing and collage of intersecting colors. The film could not have come along at a better time, intersecting with the mid-century modern aesthetic that so ruled the scene (the opening credits remind one of Saul Bass and Saturday morning cartoons), in which bright, almost unreal colors were still so damn marketable.

Accompanied by clever, rhyming narration written by Raymond Queneau (the French novelist to whom Criterion fans are most indebted for writing the literary basis for Zazie dans la metro) and read by Pierre Dux, it gives Resnais and Vierny’s spectacular images an arch sensibility, a slight remove, a hint of theatricality from which the director would continue to benefit as his career hurdled onward. These days, Resnais would hardly be Resnais without being able to give some sort of nod to the inherent artificiality, the grand movie-ness of his creations (the stage-like sets in Private Fears in Public Places, the 20th Century Fox theme music in Wild Grass, the very title of You Ain’t Seen Nothin’ Yet), but in 1959, he was still a Very Serious Filmmaker, with only room in a small corporate documentary to play with his form in such ways, turning what’s essential a commercial into a Dr. Seuss-esque bit of amazement at modern technological advances.

I should also mention, since the Northwest Film Center is asking then audiences take such a leap, that this would doubtlessly benefit from being seen on the big screen. Shot in anamorphic widescreen (which, when combined with the color aspect, is like a corporate documentary in 2013 being shot in IMAX 3D), I can only imagine how wondrous it would look in the Portland Art Museum’s grand Whitsell auditorium, every corner of your eye filled with its bold, bright, beautiful colors. Even on Criterion’s Blu-ray release of Marienbad, the image is grand, but oh, to see it on the big screen. It plays there Friday, January 10th at 7pm, along with John Smith’s 1991 doc, the longer Slow Glass, which itself sounds fascinating.

![Bergman Island (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/bergman-island-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/this-is-not-a-burial-its-a-resurrection-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![Lars von Trier's Europe Trilogy (The Criterion Collection) [The Element of Crime/Epidemic/Europa] [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/lars-von-triers-europe-trilogy-the-criterion-collection-the-element-of-400x496.jpg)

![Imitation of Life (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/imitation-of-life-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (The Criterion Collection) [4K UHD]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/the-adventures-of-baron-munchausen-the-criterion-collection-4k-uhd-400x496.jpg)

![Cooley High [Criterion Collection] [Blu-ray] [1975]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/cooley-high-criterion-collection-blu-ray-1975-400x496.jpg)