The natural and technological disasters that have fallen upon Japan over the past ten days have undoubtedly drawn the attention of just about anyone capable of feeling empathy for people who suffer so terribly and undeservedly. Many other parts of the world have been hit hard by earthquakes, tsunamis and other calamities like war or famine, both in recent times and over the course of history. But the plight of Japan seems especially unsettling, especially as the threat of further damage to the population and environment from radiation exposure continues.

Given that nation’s tragic history of being the only society to endure a direct nuclear attack, and Japan’s subsequent rise to be (in my opinion anyway) one of the most admirable contributors to global civilization in the latter half of the 20th century, I had no choice but to choose a Japanese film for this week’s Eclipse review. There are many titles to choose from, but the obvious choice to me was No Regrets for Our Youth, from Eclipse Series 7: Postwar Kurosawa.

I’m not the only one with this idea, as No Regrets for Our Youth is also the lead feature on Criterion’s Hulu Plus channel, with a link to the American Red Cross relief efforts in Japan. Released in 1946, when the ruins of World War II were still smoldering across Asia and Europe, it’s a remarkably brave and poignant melodrama that takes place in the years between 1933 and the then-present day, a moment in Japanese history when the nation was still grappling with intense self-recrimination following the humiliation of defeat.

Given that everyone in Kurosawa’s original audience had just lived through these years (and no doubt mourning many of their family and friends who did not survive them), I was amazed at how well he balanced his messages of confrontation toward those who pushed Japan on the path of militarism and those who went along with the prevailing sentiments, without resorting to simplistic shaming or self-righteous posturing.

The film deals with Japan’s descent into fascism, and the brutal cost that this massive error inflicted on their society and those victimized by its imperialistic expansionism. In short, it’s a “disaster movie” of a different sort, though one totally bereft of special effects or any attempt to simulate the carnage and chaos of the war itself. I can’t blame Kurosawa for not wanting to go there; for one, there were very limited financial resources available to make a film of any sort, much less a recreation of the military campaigns that were still too raw and painful to revisit. And even if the money was available, I doubt that the Japanese citizens of that time would have found much entertainment value in such a spectacle. Not to mention the difficulties of getting such scenes through the censorship of the USA occupation force that governed Japan in the late 1940s.

So rather than focus on the plight of the soldiers or whatever intrigues took place at the highest levels of the government or military command centers, Kurosawa directs our attention to a fairly typical, middle class scenario. Yukie, played with exquisite poise by Setsuko Hara (most famous for her central role in Ozu’s Tokyo Story, Late Spring and many other films), is the daughter of a professor at Kyoto University. As right-wing authoritarianism establishes its foothold in the Japanese government, Professor Yagihara starts to feel pressure from nervous administrators who dislike the scrutiny that his anti-militaristic views have generated.

He’s urged to either recant his teaching or resign his post, and this interference stirs up a minor rebellion from students sympathetic to his ideas and supportive of a beloved teacher. Yukie, just coming of age herself and especially admired by two of her father’s students, the radical firebrand Noge and the bland but sensible Itokawa, is disdainful of all the political debates and controversies. She just wants to enjoy life on simple and uncomplicated terms – but she’s far from the vain and shallow stereotype that some might expect, as she indicates with her lyrical piano playing and soulful insight into the character of the two men for whom she feels a genuine, though conflicted, affection.

The story develops over the course of pivotal scenes separated by gaps of several years, as we see the grip of fear and oppression tighten up on everyone involved. Noge’s idealism and bravado are challenged as his opinions run ever more contrary to the party line and become criminalized. Itokawa’s sincere pragmatism pushes him to serve as an enabler of the corrupt power structure despite his inherent dislike of the direction things are going.

Professor Yagihara is torn by the strength of his conscience to stand up for what is right in trying to slow down the military machine and his loyal sense of duty to not have a negative effect on the education of his students by getting too far out of line. Yukie’s love of Noge is prevented an open expression, partly because of his own reticence to reciprocate her feelings and also because his activities bring about legal consequences that prevent them from being together. She ultimately leaves home to make her own way in the world by working menial jobs in Tokyo, much to her parents’ disappointment as they know she’s gifted and capable of so much more.

Without going much further into the details, Yukie and Noge do eventually wind up as a couple, but only after the course of life and society has made it difficult if not impossible for them to live in the peaceful freedom that she envisioned in the earlier, happier days of their relationship. Even though Noge has, under a government-sponsored program of coercion, distanced himself from the leftist ideology of his youth, suspicions about his affiliations and trustworthiness remain, leading to trouble for both him and Yukie as the 1930s draw to a close and Japan’s course to all-out war in Asia and ultimately with the United States becomes irreversible.

All involved in the sad unfolding of events suffer terribly, yet Yukie emerges from the ordeal ennobled by her sacrifice and her refusal to acquiesce to the powers who could have made her life more comfortable, had she accepted the compromise demanded of her.

On the film making side of things, Kurosawa turns out what can easily be considered his first major triumph, handling highly sensitive and profound subject matter at a crucial moment in Japan’s history. Here he’s still a young director, experimenting with styles and techniques he’s picked up from domestic and international predecessors, some of which work more successfully than others. (Among the few clunkers were a strange montage of Yukie striking emotive poses when she hears that Noge has left the country and a somewhat botched point-of-view fall down a staircase, the kind of shot that is best left to Max Ophuls, if you ask me.)

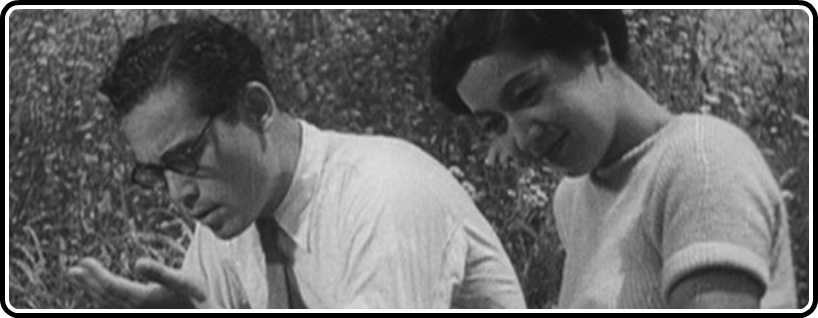

Still, it’s exciting to see his cinematic maturing process, Several scenes throughout the film prove to be the seedlings of techniques and visual motifs (like downpouring rain) that would come to epitomize some of the greatest moments in Kurosawa’s amazing career, including a magical sequence near the beginning of the film, where Yukie is being playfully chased by a pack of her father’s students through the woods. It’s a wonderful preview of numerous, more familiar cross-cutting action shots from films like Rashomon, Seven Samurai, Throne of Blood and others. And the rice-planting scene that closes out Seven Samurai will be enhanced by a whole new layer of contextual significance after watching No Regrets for Our Youth.

In centering the action on the effects that war and military fanaticism had on one female protagonist and her family, Kurosawa reminds us that even in the grand sweep of major historic cataclysms, tragic poignancy is most comprehensible when broken down to the individual level – as appalling as the cumulative losses and statistics may be. There are obvious differences between a disaster that strikes as a result of a ten-year slide into myopic, paranoid nationalism and the aftermath of a purely natural and unavoidable event like an earthquake and tsunami.

But history demonstrates that the human spirit is resilient enough to persevere in such devastating circumstances, and Kurosawa understands the small, humble role that a film like No Regrets for Our Youth can have in summoning up his audience’s courage and determination to carry on, to rebuild that which was lost. Both in honor of those victims who were not able to see their day of vindication and renewal, and for the sake of those young who, regardless of our mistakes and misjudgments, deserve an opportunity to live in peace and freedom, No Regrets for Our Youth inspires us to remain strong even when all seems lost. I pray that the people of Japan, as they set about their latest task of rebuilding shattered communities, find within their ranks an artist capable of giving their story the expression it truly deserves.

This post is part of a week-long Japanese Cinema Blogathon, urging fans of films from Japan to donate to humanitarian relief efforts. Click the image above to see other reviews in this series, and this link to choose an organization to support! CriterionCast.com is also giving away a prize to a random winner among all entries who send us a copy of their donation receipt (with confidential information blocked or removed, of course.)

![Bergman Island (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/bergman-island-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/this-is-not-a-burial-its-a-resurrection-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![Lars von Trier's Europe Trilogy (The Criterion Collection) [The Element of Crime/Epidemic/Europa] [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/lars-von-triers-europe-trilogy-the-criterion-collection-the-element-of-400x496.jpg)

![Imitation of Life (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/imitation-of-life-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (The Criterion Collection) [4K UHD]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/the-adventures-of-baron-munchausen-the-criterion-collection-4k-uhd-400x496.jpg)

![Cooley High [Criterion Collection] [Blu-ray] [1975]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/cooley-high-criterion-collection-blu-ray-1975-400x496.jpg)

This is an amazing contirbution to the blogathon, thanks for this great write up!

http://japancinema.net/2011/03/15/japanese-cinema-blogathon-to-aid-earthquake-and-tsunami-relief/

Thank you Marcello. I was very happy to be a part of this effort, and your feedback is very encouraging. I’m glad you liked my review! :)