My recent viewing of Masahiro Shinoda’s Pale Flower (reviewed on my Criterion Reflections blog) stirred up some interest in learning more about the industrial port city of Yokohama, where that film is set. As major world metropolises go, it’s an easy city to study up on since its existence as such is of such recent origin. Nowadays, after Tokyo, it’s the second largest city in Japan, with a population of 3.7 million. Situated just about at the mid-point on Japan’s lengthy Pacific Ocean coastline, Yokohama’s role in Japanese culture and history was insignificant up until the middle of the 19th century, when it happened to be the landing spot of Commodore Perry, whose uninvited breach of Edo-period isolationism forced Japan to open up their society to Western trade and its accompanying influences.

In response to that crisis, Yokohama was transformed from a small, anonymous fishing village to a major international port and commercial hub. As such, it was the place where Western civilization established its first and strongest foothold, introducing all sorts of new ideas and attitudes that challenged Japan’s understanding of itself as a society. No wonder then that when 20th century Japanese film directors wanted to tell a story portraying the friction stirred up by the clash of tradition and new values imported from the outside world, Yokohama served as an ideal setting. That was the case in 1964’s Pale Flower, and certainly added to the dramatic tension of Akira Kurosawa’s masterpiece High and Low, released a year earlier, as both films vividly capture the moral fatigue and sense of rootlessness felt by many as the nation rebounded economically from the calamity of World War II, but at a heavy price in terms of both individual and social sense of purpose and solidarity. (Shohei Imamura’s Pigs and Battleships (1961), dealing with similar themes, is set near the American military base in Yokosuka, about 12 miles to the south of Yokohama.)

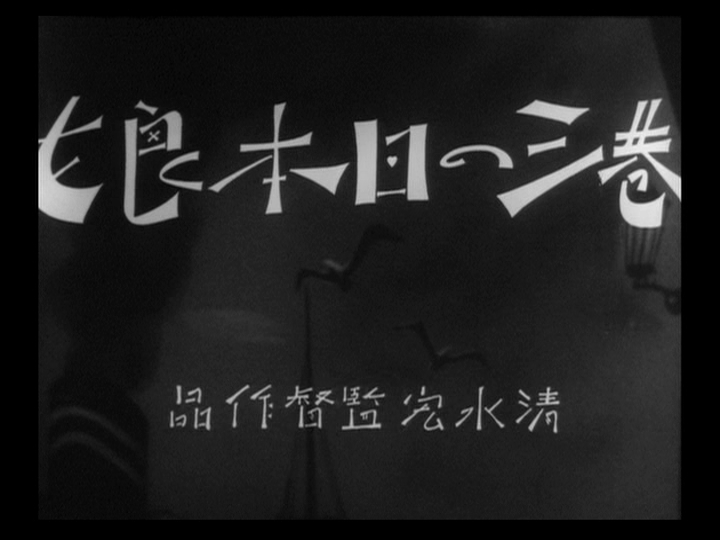

But well before anyone in Japan could even begin to conceive of the devastation that was to occur during the 1940s, Yokohama still served as a crucial flashpoint in Japan’s struggle to define itself as it became more difficult to maintain its proud independence as an island nation separated from and seemingly indifferent to the rest of the world. Despite its brevity (a mere 71 minutes) and fairly conventional structure as a tragic-romantic melodrama, Hiroshi Shimizu’s 1933 film Japanese Girls at the Harbor is a poignant portrayal of a society under ideological siege, leaving individuals confused and heart-broken in their attempts to find their place in a new order.

Japanese Girls at the Harbor is the oldest film in Eclipse Series 15: Travels with Hiroshi Shimizu, and the only silent offering in that box. It’s also the last one of the four in that set that I have to write up in this column. The others (Mr. Thank You, The Masseurs and a Woman, Ornamental Hairpin) were all viewed by me too far apart to acquire a cumulative sense of Shimizu’s distinctives as an auteur, but that’s a situation I’ll try to remedy in the near future, and it shouldn’t take too long as each of the films are pretty short. I do know that I’ve enjoyed each of them; the overall impression they create is that Shimizu was a sensitive and adventurous filmmaker who pushed then-current filmmaking technology to the limit, especially in terms of location shooting, hence the “travels” mentioned in the title of this collection. Sadly, fate was not so kind to Shimizu’s output or lasting reputation – despite being one of Japan’s most prolific of all filmmakers (directing somewhere in the neighborhood of 160 films between 1924 and 1959, most of them are either lost or exceedingly difficult to find, and his career is almost forgotten, especially in comparison to his peers like Ozu, Mizoguchi and Naruse, who all respected Shimizu’s accomplishments and influence. This Eclipse box represents one half of the most readily available collection of eight of his films that was released several years ago in Japan. I’m fortunate enough to have copies of the other four, which mark his postwar pivot into directing mainly children’s films, though of a higher artistic caliber than one might initially think when considering that cinematic genre.

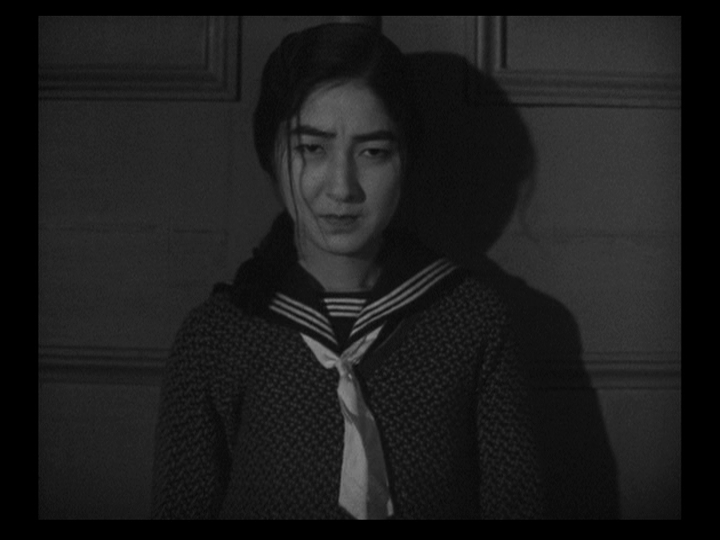

As I alluded to above, the storyline of Japanese Girls at the Harbor is generic enough to be adapted in a wide variety of situations. In its basic mechanics, there’s not much in the way of plot development that the average viewers hasn’t seen before. Sunako and Dora are the young women referred to in the title, and we see them dressed in schoolgirl outfits at the beginning of their story. Within the first few minutes, after we’ve been granted a brief visual tour through Yokohama’s docks that host massive freighters and luxury liners alike, we learn of the strong bond of friendship they’ve formed, that will inevitably be put to the test. As is so often the case with teenage girls, a romantic entanglement involving Henry, a handsome boy that they both like, stirs up tensions – especially after Sunako flirts and pouts her way into getting a ride on Henry’s motorcycle, leaving poor Dora to walk home all by herself.

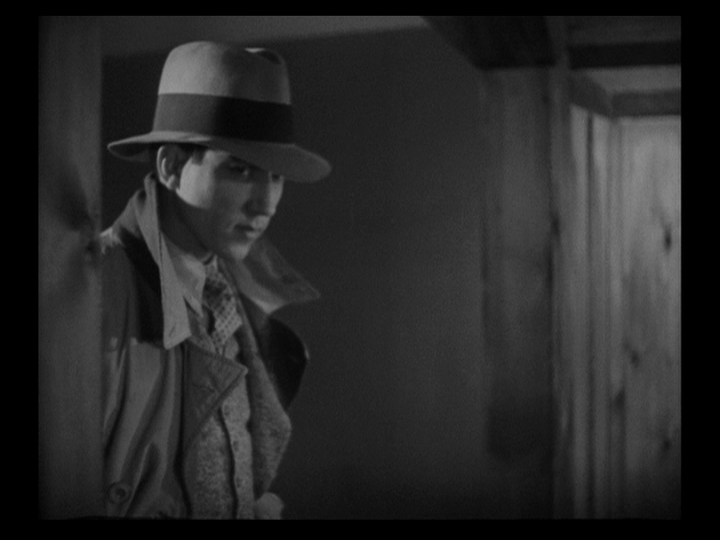

Dora and Sunako both attend a private Christian high school located atop “The Bluff,” a neighborhood overlooking Yokohama’s central basin and coastline that was set aside back in the 19th century for Westerners to settle into, presumably because of the geographic separation that was built into the locale. The existence of a Christian school in the city is not really dwelt upon by Shimizu as an obvious intrusion, nor does he go out of his way to disparage the institution in any way – the symbolism of the cross, the obviously Westernized attire that they wear and even Anglo-based names of characters like “Henry” and “Dora” speak for themselves. But Shimizu does take advantage of the picturesque locale, returning to that same scenic vista on a few occasions to punctuate his narrative and give the story, which unfolds over the course of perhaps a decade or so, a recurrent dramatic rhythm as we follow each character through their changes. And after it’s been established that Henry has taken a particular liking to frisky Sunako over the more prim and modest Dora, the first big dramatic wrench is thrown into the works when we discover that he’s just toying with the girls. His more intimate companion is a brazen vamp, Yoko Sheridan (another name that points to some degree of mixed marriages that have taken place in earlier generations between foreigners and Japanese locals.)

Henry’s character is revealed to be that of an unscrupulous playboy who considers it no big thing at all to trifle with the hearts of impressionable girls whose lack of experience and overflow of powerful emotions make them ill-equipped to withstand the charms of such a callous but privileged snob. Still, Henry himself is quite unprepared to deal with the firestorm of feelings that his caddish behavior ignites, as it leads to a shockingly violent showdown between the jilted Sunako and the smirking Yoko – in the sanctuary of their school’s chapel, no less.

I won’t spell out all the events that precede and follow that critical confrontation, but it does set the stage for developments that take a darker and more tragic turn than the initial set-up might have led us to expect. To indicate some passage of time, Shimizu takes us on one of his “travels” that captures just a brief glimpse of the bustling portside activity of old pre-war Yokohama.

When the action resumes, we see that Dora and Sunako have gone their separate ways. Somewhat surprisingly, Henry and Dora wind up together, a blandly domesticated married couple living out a comfortably warped Japanese interpretation of what we might call “the American dream,” complete with suburban-ish clapboard house and white picket fence, interior furnishings, wallpaper, sofa and modern attire. Meanwhile, Sunako has hit the skids, shacking up with Miura, a penniless artist who struggles to make any kind of a living selling portraits on the streets of Yokohama’s red light district.

Miura’s inability to exploit his talent pushes Sunako into the only kind of employment seemingly available to a woman of her status – a barmaid at a seedy hotel who loiters around every evening looking for male customers who seek her out to provide more intimate services. One fateful evening, after discussing recently-heard rumors about what’s become of their dear old mutual friend, Henry finds his way to Sunako’s haunt, rekindling the long-dormant sparks of a once-heated relationship in the process. With the tranquility of Henry and Dora’s marital bond now threatened, and with Sunako sensing that perhaps if she played things right, she could ditch her deadbeat artist for a handsome old flame who’s managed to make something of himself, the melodramatic chord is struck that will resonate over the final act of Japanese Girls at the Harbor.

So without divulging much more of the specifics of what happens in this swiftly moving tale, let me just articulate my admiration for some of Shimizu’s more interesting artistic flourishes. I definitely get the sense that he was, like Mikio Naruse around this same time in films like Flunky, Work Hard, attempting to stretch his own boundaries of how to tell a story (though he hardly matches Naruse in the sheer radicalism of his efforts.) The most striking visual innovation in Japanese Girls at the Harbor is Shimizu’s repeated use of characters who disappear in a fade as they make their exit, a fascinating bit of trick photography that renders them as phantoms, casting a vaguely ethereal pall over the motions of betrayal, abandonment and reconciliation that take place throughout the film’s second half. It’s as if Shimizu is alerting us to the fact that, as painful as these relational transitions can be, they are also quite ordinary and common, mere passages of life that we have to get through with as little sentimental attachment as possible so as to be ready for whatever new direction life draws us into.

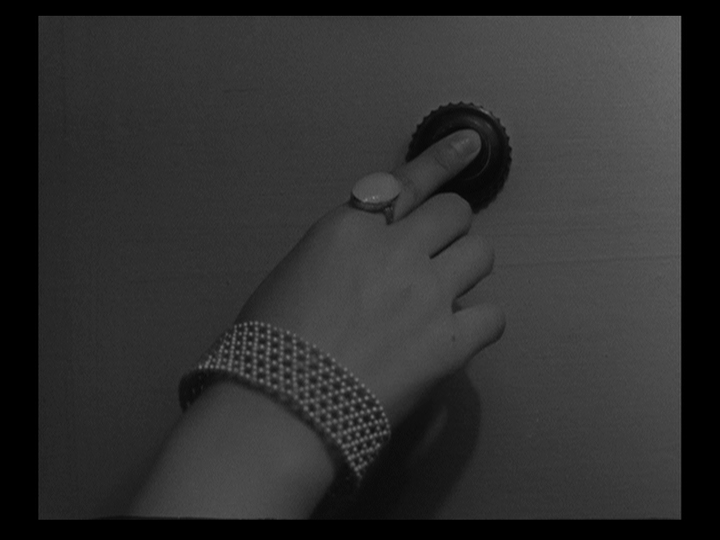

And again, without going out of his way to draw our attention, Shimizu’s employment of different types of fashion (clothing, jewelry, hairstyles, etc.) says a lot about the transitional phase that Yokohaman society was in at this particular juncture, as we see the collision of prosperous respectability and impoverished vulgarity, each warily sizing up where they rank in the estimation of their distrusted counterparts.

There are also numerous instances of what eventually became a celebrated Ozu trademark, the nicely framed and carefully placed “pillow shot” – those brief interjections of something picturesque and evocative that don’t necessarily advance the narrative, but provide a pause for us to absorb what we’ve just seen and prepare for the next transition to come. Though Ozu carried the practice forward and refined it to an exquisite degree, Shimizu shows it to be fairly standard practice in Japanese cinema of that era.

As Japanese Girls at the Harbor approaches its bittersweet conclusion, Shimizu continues to impress with his evocative, poetic sensibility. A crucial sequence near the end of the film illustrates a character’s imminent demise with bleak imagery of “dying alone on a rainy night”: an abandoned shoe, a fractured vase at the base of a dribbling gutter; a wilted flower and an empty vessel, forgotten in the storm.

Though his screen time is fairly limited in an important but fairly minor supporting role, I also enjoyed seeing Tatsuo Saito turn in another fine performance. He had significant parts in early Ozu films like Tokyo Chorus and I Was Born, But…, and I really dig his cool Bohemian vibe in just about every film of his I’ve ever seen.

By indirectly but unmistakably raising important issues of Japanese identity through the nation’s interactions with other religious traditions, the society’s ability to support nonconformist artistic temperaments and women who have fallen out of favor and the irreversible intrusion of foreign influence through finance and other cultural exploits, Shimizu added substantial heft to what otherwise might be dismissed as a plaintive tear-jerker. As is common in this period of Japanese cinema, the final scenes of Japanese Girls at the Harbor may seem a bit convenient and tidy, even though the solution that we’re presented is far from a guarantee of future happiness. Indeed, Shimizu could even be treading on the verge of being regarded as subversive toward the increasingly authoritarian and fascistic trends that were emerging at that time in Japan, in pointing outward or even toward a thorough abandonment of one’s past as the place to look for resolutions to his characters’ central conflicts. Sometimes one has to leave the safety of the port and head out into wide-open seas to perceive life in its proper perspective.

![Bergman Island (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/bergman-island-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/this-is-not-a-burial-its-a-resurrection-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![Lars von Trier's Europe Trilogy (The Criterion Collection) [The Element of Crime/Epidemic/Europa] [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/lars-von-triers-europe-trilogy-the-criterion-collection-the-element-of-400x496.jpg)

![Imitation of Life (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/imitation-of-life-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (The Criterion Collection) [4K UHD]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/the-adventures-of-baron-munchausen-the-criterion-collection-4k-uhd-400x496.jpg)

![Cooley High [Criterion Collection] [Blu-ray] [1975]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/cooley-high-criterion-collection-blu-ray-1975-400x496.jpg)