Earlier this week, many fans of classic 50s and 60s era Japanese cinema experienced the emotional dissonance of sadness over news reporting the death of Nagisa Oshima and elation over Criterion’s announcement that same day of an upcoming release gathering four pivotal early works of Masaki Kobayashi. Both directors were responsible for some of the most searingly intense films of their generation, and with the new Masaki Kobayashi Against the System set, due in April, they each have a place carved out in the Eclipse Series. While each deserve the respectful attention that Tuesday’s news directed their way, I’m here today to heap a little praise on one of their contemporaries, the slightly less celebrated Koreyoshi Kurahara. As more of a journeyman director-for-hire, Kurahara never attained the ambitious heights that Kobayashi reached in epics like The Human Condition or Harakiri, nor did he generate anywhere near the degree of scandal and outrage that Oshima provoked in films like Night and Fog in Japan and In the Realm of the Senses, among others. Still, his distinctive outlook makes Eclipse Series 28: The Warped World of Koreyoshi Kurahara just as essential a document as the Oshima and (yet to come) Kobayashi collections to understand what was happening in this fascinating transitional era in Japanese film and culture.

Today I’m focusing on Kurahara’s fun and frantic foray into pop culture, I Hate But Love, and the reason I’m doing so is that it’s the last film of 1962 that I have yet to review in my chronological exploration of Criterion-related films on DVD and Blu-ray. Over on my Criterion Reflections blog, I recently wrote about Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le doulos, leaving just this title on my list of 1962 releases yet to be reviewed either here or over there. I can’t be sure of where exactly it fits on the chronology, since IMDb doesn’t list a specific release date… so I’m assuming no later than 12/31/62. More likely, I Hate But Love feels like a summertime release, because of its bright color palette, its breezy road movie narrative structure and the numerous touches of comedic whimsy (showing more than a little skin along the way) that surely made this movie very appealing to teens and young adults back in the day.

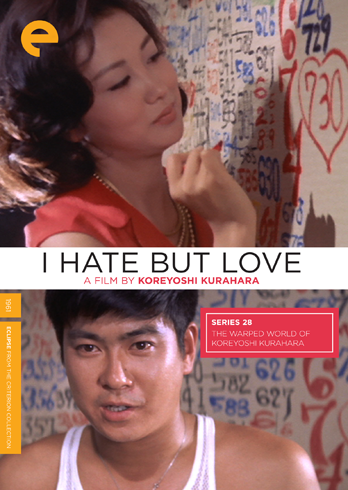

As far as the director Kurahara is concerned (that’s his screen credit in the image above), he gets due respect for his distinctive touches (the spiraling camera work and well-modulated pacing that deftly alternates passages of quiet reflexive tranquility with bursts of surprisingly rough violence, considering its era and the pop stars involved with the project.) But make no mistake, I Hate But Love was marketed first and foremost as a YUJIRO picture… and if that name doesn’t mean much to you, chances are that you are just beginning your acquaintance with the popular Japanese film scene of this era.

Yujiro Ishihara was indisputably the biggest Japanese screen idol of that time. Sure, Toshiro Mifune, Tatsuya Nakadai and others were impressive actors and reliable box office draws, but Yu-chan was an overwhelming presence, especially among the young, to whom he epitomized their restless energy, their wary questioning of what the previous war-torn generation had bequeathed to them and a willingness to break more radically with Japan’s cultural rigidity than their elders ever thought permissible. Two of his films have already been featured in this column (I Am Waiting and Rusty Knife) and his breakout role in Crazed Fruit that preceded those other two was covered on my blog. By the time I Hate But Love was released, at the pinnacle of Yujiro’s celebrity, he had made so many films and was such a ubiquitous screen presence that perhaps the easiest casting decision of the entire film consisted of letting him play a slightly modified version of himself: a popular but jaded TV and radio personality who is accosted by fans and admirers whenever he appears in public. Comparisons between Yujiro and Elvis Presley in the early 60s phases of their careers are not at all unreasonable, especially since each of them were exploited by management to milk every last drop of profit from their adoring fans, often by appearing in cheesy, paint-by-numbers movie scripts that made few demands on their time or mental energy. Naturally, that lent a certain degree of shallowness to many of the productions, but from time to time, both Elvis and Yujiro found their way into films that stood out from the pack and actually said something worth contemplating after the toe-tapping tunes faded out. Though my exposure to Yujiro’s films is very limited, I Hate but Love seems to easily belong in that category of substantive works, wheat among the chaff.

Besides the director and the male lead, another appealing aspect of I Hate But Love is found in Yujiro’s female counterpart. His previous leading lady, Mie Kitahara, had by now retired from the movie industry after becoming Yujiro’s real-life wife, putting her teen idol days behind her just as the 1960s got underway. Her spot was more than capably occupied by the beautiful, versatile and prolific Ruriko Asaoka, who appeared in an average of 10 films a year between 1955 and 1967. She’s only made it into two Criterion films so far, this one and Thirst for Love, also in the same Kurahara box set. In the later film, she shows a darker, more dramatic side of her acting abilities – though no one should mistake I Hate But Love for a fluffy, sanitized rom-com of the sort that Elvis and Ann-Margret or Frankie Avalon and Annette Funicello were romping through right around the same time. The comedic whimsy and cutesy moments occur in this film, but Kurahara plunges both of his highly photogenic stars into some unexpectedly intense and gut-wrenching moments, erupting so quickly that even today’s savvy viewers won’t see them coming.

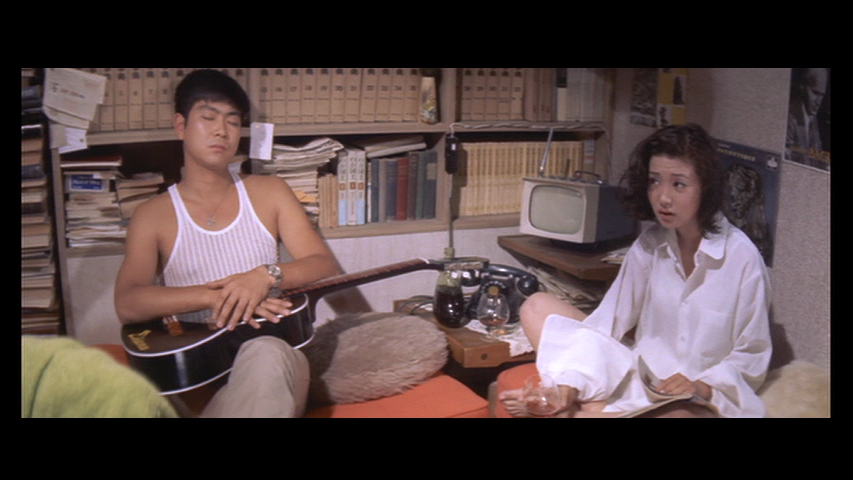

But like I was saying, never underestimate the power of peek-a-boo sex appeal to draw in the more easily distracted viewers. Not all that different than what Harmony Korine did in casting a bevy of nubile Disney starlets, putting them in bikinis and slingin’ em back at us in the Spring Breakers trailers that hit just the other day. As we see happening now, I”m sure rumors and previews of Ruriko’s sashays across the screen in her bra and panties circulated well in advance of I Hate But Love‘s debut. And just to be fair, Yujiro gives his admirers equal time, strutting around shirtless and even stripping down to his tighty-whities on a few occasions to show off his hunka-hunka burnin’ love.

I Hate But Love‘s story pits Daisuku, the bored and burned out superstar, in a manic-depressive romantic grudge match against his manager Noriko, who not only schedules his every waking hour to the bursting point, but also shows indicators of OCD as she records each day that they’ve been a couple in bright colors on the wall of their apartment. You can see the graffiti on the DVD cover image at the bottom of the post. What makes their relationship even more peculiar is that they impose strict limitations on any intimacies between them – to the extent that they don’t even kiss, though we see them straining under the burden of upholding that restriction all throughout the film. In the moments where they’re not struggling with their lust, they vacillate between intense loathing of the difficulties each puts the other through and passages of hopeless boredom, where nothing at all happens and no easy answers to the question “what shall we do with our lives?” are to be found.

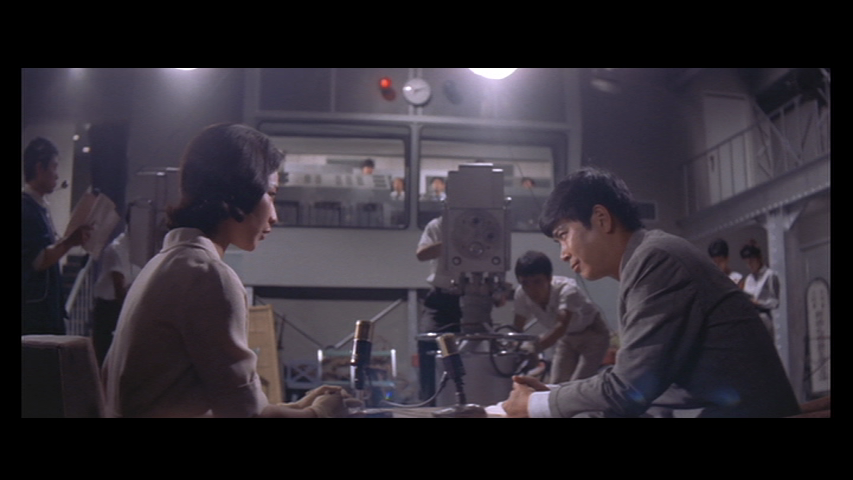

Despite all the trappings of being young, rich, beautiful and sensationally popular, there’s a big void in Daisaku’s life. He knows that something needs to change, but he’s not sure what to do or where to look. One evening while broadcasting his live interview show on TV, he stumbles upon something resembling a purpose. His guest, Yoshiko, is a young woman who’s raised money to purchase a worn-out old Jeep, the clunky army-surplus kind, not the cool SUV we see bearing that logo nowadays. The vehicle needs to be delivered to Toshio, the man she loves, a doctor working in the remotest end of Japan’s southern mainland, a rugged mountain village where the technological conveniences and dynamic energy of modern Japan are nowhere to be found. Yoshiko’s devotion to her man, whom she has never met but only corresponded with by letters, conjured up a weirdly dissociative parallel with the Manti Te’o “dead girlfriend” hoax in my mind, which I won’t bother exploring here any further.

Daisaku is so impressed by Yoshiko’s account, and her plea for support, that he impulsively decides while on the air to deliver that Jeep. His motivations aren’t really altruistic at all – he just wants to see for himself whether or not such pure love as Yoshiko claims for Toshio really exists. Of course, this long and grueling trip through the southwestern regions of Japan isn’t on his packed schedule, but he goes for it anyway, creating all sorts of grief for Noriko as both his manager and his frustrated would-be lover. The emotional tug of war escalates quickly, through stages of grief, shock, frustration, sadness, despair, sorrow and self-pity. Some of those phases are played for laughs, but others are delivered with gritty, occasionally violent intensity. For all of the farcical elements scattered throughout I Hate But Love and its exaggerated conceit of its runaway superstar and the spitfire in red heels dogging him every step of the way, the psycho-sexual sparks that fly between Daisaku and Noriko are genuinely engaging.

Also of great interest to anyone who enjoys rare views from Japan’s past are I Hate But Love‘s extended road trip scenes. My friend and former Eclipse Viewer cohost Robert Nishimura lives near the area where the film’s later portions took place, and he recently emailed me to confirm that the mountainous regions in particular hadn’t changed much from the glimpses we get in this movie. And beyond the vintage landscapes, architecture, vehicles and occasional landmarks in Osaka, Kyoto, Hiroshima and elsewhere, Kurahara also includes scenes like the one above, showing some kind of street festival/parade that livened up the action and probably generated a lot of local interest in seeing the film when it finally hit theaters. As the only color film included in this set, I Hate But Love‘s vibrant wide-screen compositions make it a nice change of pace from the monochrome look we get from most of the “important” Japanese films of the early 60s.

Kurahara’s most strident but also prescient editorial contributions come at us through his deservedly cynical deconstruction of the celebrity media machine. As their superstar money maker Daisaku furiously navigates his jeep down the highway, leaving Tokyo and its constricting madness in his rear-view mirror, we see his producer Ichiro give chase, tracking him by hidden cameras in passing vehicles and hunting him down by helicopter overhead. A fake narrative is constructed to sanitize Daisuku’s rebellion, transforming his AWOL escapade into a noble “humanistic” mission in order to win the public’s admiration for going so bravely off-script. The easily bedazzled Japanese mass audience isn’t portrayed in all that flattering terms either, as they’re often portrayed mass, gullible gawkers who obediently point their eyes and their loyalty wherever the camera and omniscient TV narrator steers them.

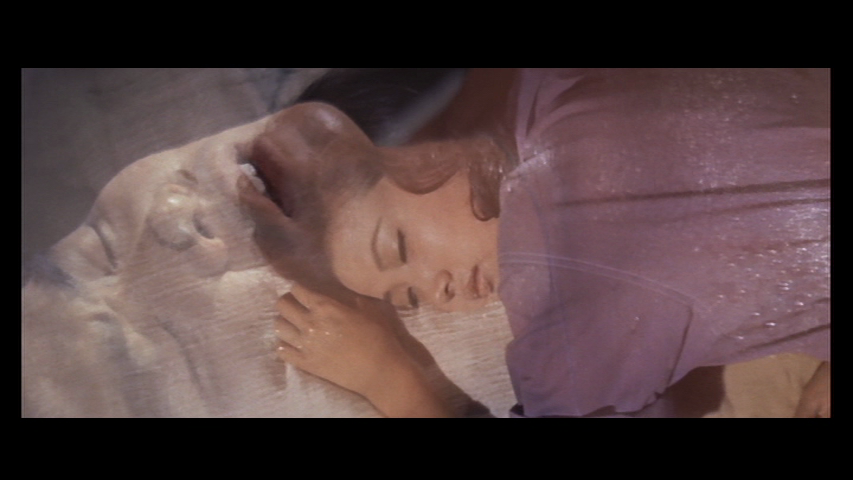

The local color, the sardonic social commentary and Kurahara’s trademark shots spinning up into the sun or looking down on small, frail humanity like so many insects sprawled out on the ground, all lend themselves favorably to what boils down to a satisfyingly rambunctious, untamed and persistently surprising film. I Hate But Love gives viewers unfamiliar with Yujiro and Ruriko a fresh opportunity to see the mechanics behind media-driven mega-personalities without having to set aside the baggage that accompanies our viewing of more familiar Western superstars over the past 50 years. Once you become accustomed to their unique charisma, the twists, turns and ultimate culmination of their relationship on a hot sunny mountainside (after they make their way over muddy roads that reminded me of Being John Malkovich‘s excremental “mind tunnel”) make a return visit all the more delightful and compelling. I Hate But Love has something to identify with to for just about anyone who’s experienced the sublime agonies and ecstasies that accompany each of those emotions.

![Bergman Island (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/bergman-island-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/this-is-not-a-burial-its-a-resurrection-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![Lars von Trier's Europe Trilogy (The Criterion Collection) [The Element of Crime/Epidemic/Europa] [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/lars-von-triers-europe-trilogy-the-criterion-collection-the-element-of-400x496.jpg)

![Imitation of Life (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/imitation-of-life-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (The Criterion Collection) [4K UHD]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/the-adventures-of-baron-munchausen-the-criterion-collection-4k-uhd-400x496.jpg)

![Cooley High [Criterion Collection] [Blu-ray] [1975]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/cooley-high-criterion-collection-blu-ray-1975-400x496.jpg)