A wide swath of North America received a wintry blast of historic magnitude last week. It snowed, and snowed, and kept on snowing, icing, freezing and blowing over the course of several days. The storm has since let up but the piles of snow remain and for many of us, they won’t be going anywhere for quite awhile, regardless of what the groundhog saw last Wednesday morning.

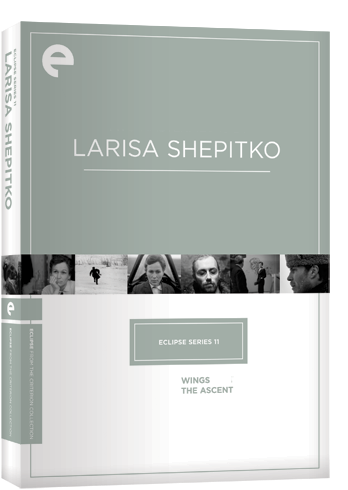

But the harsh weather played nicely into my plans for this column. I’d already scheduled this week’s film on the basis of it being a ‘winter war movie,’ figuring that early February would be the perfect time in bleak midwinter to watch a grim story of suffering and survival set in a bitter frozen landscape. It’s The Ascent, from Eclipse Series 11: Larisa Shepitko.

I went into my first viewing of The Ascent fairly uninformed about the story, only knowing of its reputation for being emotionally intense and widely admired due to its powerful imagery and raw naturalism. One only has to look at the DVD cover and a few other stills to surmise that it focuses on the plight of soldiers at war. Sure enough, The Ascent presents a stunning vignette from the winter of 1942, when Nazi invaders still held the upper hand on all fronts of the war, committing their crimes and atrocities with seeming impunity, confident in their eventual triumph when a new order of cruelty and authoritarian terror would become the norm. Even though history tells us they lost the war, their mastery of torture and repression have sadly been passed on to others, an underlying truth that allows The Ascent to transcend its historical underpinnings and speak meaningfully across time and cultural differences.

The film opens with the piteous sight of a village being evacuated in advance of a German onslaught. A small troop of armed men accompanies the women and children who are now forced to relocate deeper into the woods where they can hide. But the last scraps of food have now been eaten, and more provisions need to be gathered if the refugees are to survive the ordeal and make it across the snowy wilderness to a safer place away from the battle lines. Two men, the seasoned soldier Rybak, and Sotnikov, a math teacher who’s just been given a gun and told to fight as best he can, set out to find a nearby farmhouse and see what they can bring back to feed their people.

The open spaces and high-contrast cinematography deliver a chilling effect, in both senses of the word. I just felt cold watching bodies stagger in the chaos of bright white space, slogging through thigh-high snow drifts, exposed to the elements but having to move forward anyway. And the danger that devours them within, from the lack of food, and without, from the murderous soldiers who pursued them, was palpable. This clip offers the first 8 minutes of the film, without subtitles, though you’ll be able to figure out most of what’s being communicated, since the messages are so primal:

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4LVD9S2dVxw&fs=1&hl=en_US]

As emotive as the early scenes of deprivation are, they only set the stage for The Ascent‘s gathering power and harrowing conclusion. Rybak and Sotnikov are forced to take increased risks after their initial plan to find food turns up empty. They venture closer to the front lines, where they meet an old man who admits to collaborating with the Nazis for the sake of his own survival. Rybak scolds him for his cowardice, but they leave the homestead with some desperately needed provisions and set out to rejoin their company.

They’re unable to complete the trip though, as Sotnikov is wounded after their trail is picked up by a German patrol. Rybak has the opportunity to get away and deliver his precious cargo of food to the women and children awaiting him in the forest, but he’d have to leave Sotnikov behind to die in the open field. He has to make a tough decision: save himself and feed the people, or risk everything for the sake of a wounded friend who might not even make it? Little does Rybak know that whatever pangs of conscience he wrestled with in weighing his options here are mere coin flips in comparison to the heavier choices awaiting him over the last half of The Ascent.

I’m reluctant to lay out more of the plot here, since I doubt too many readers have seen this film and it definitely deserves a clean, spoiler free first watch. Let it be sufficient to say that the deeper you let yourself be engrossed in Rybak’s and Sotnikov’s dilemma, the more disturbed and riveted you’ll be as they meet their respective fates. Larisa Shepitko, who died two years after this, her final film, was released, demonstrates extraordinary skill in pacing her story and laying out its profound themes, allowing each actor to stir our emotions through their naturalistic and evocative portrayals of various human responses under extreme duress.

Though The Ascent presents examples of both heroism and cowardice, the characters are not simplistic cutouts of good vs. bad, where we easily admire one and despise the other. I think Shepitko’s point isn’t to make the case for a particular role model of how we should behave if we ever found ourselves in such a horrible situation as Rybak and Sotnikov.

Rather, she’s simply demonstrating that the potentialities for both nobility and betrayal exist within all of us, that convincing arguments can be made to justify both, on the basis of principles and practicalities, either for the sake of affirming the righteousness of our cause and inspiring others to stand strong, or for the sake of staying alive in the hope of effecting change and winning the struggle in time. The Ascent asks us, what wretchedly painful price – our conscience or our life – are we willing to pay to achieve either of these worthwhile ends?

Given that The Ascent is a product of the USSR, the decision to look back on the horrific experience of Belarusian citizens under German occupation in World War II makes sense. Such a setting for the narrative provided Shepitko a perfect opportunity to critique the similarly brutal oppression practiced by the Soviet regime over the decades following the Great Patriotic War (as it’s referred to in Russia).

By incorporating her back-handed swipes at the corrupted power structure of her own day in a heroic and historically unimpeachable demonstration of the suffering endured at the hands of a despised conquering army, Shepitko was able to present the story, along with its obvious infusion of Christian mysticism, without much interference from censors.

That still didn’t guarantee a popular reception within the USSR, but it did allow The Ascent to get favorable notice within the international film community at the time. Her loss at a young age, as her talent was clearly coming into full fruition, surely deprived us of other memorable achievements and probably limited Shepitko’s eventual audience, given the obscurity and brevity of her filmography.

But The Ascent is a film deep and resonant enough in its treatment of some of life’s biggest issues that it deserves to be sought after. Its inclusion, along with her second film Wings, in this small, affordable box set is an excellent demonstration of what makes the Eclipse Series such a valuable and fascinating line of DVDs.

![Bergman Island (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/bergman-island-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/this-is-not-a-burial-its-a-resurrection-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![Lars von Trier's Europe Trilogy (The Criterion Collection) [The Element of Crime/Epidemic/Europa] [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/lars-von-triers-europe-trilogy-the-criterion-collection-the-element-of-400x496.jpg)

![Imitation of Life (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/imitation-of-life-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (The Criterion Collection) [4K UHD]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/the-adventures-of-baron-munchausen-the-criterion-collection-4k-uhd-400x496.jpg)

![Cooley High [Criterion Collection] [Blu-ray] [1975]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/cooley-high-criterion-collection-blu-ray-1975-400x496.jpg)

Absolutely brilliant film, and you do it justice in your piece, David. Well done!

On a side note, Anatoli Solonitsyn is perfect in this. Every second his character is onscreen, he’s fascinating to watch.

Thank you Marc. The Ascent is one of the more humbling Eclipse films I’ve had to write about! Such powerful themes, it’s really worthy of a standalone release in terms of quality and profundity. Maybe there just weren’t enough supplements available or Shepitko isn’t famous enough to make it commercially viable? Anyway, I’m glad Criterion released it.

I didn’t realize until you mentioned Solonitsyn that he’s the guy who played Andrei Rublev! (He’s the balding insane fiend pictured above). Thanks for bringing that to my attention. Yes, he’s a compelling presence… pure clinically detached extinguished conscience.