Few things, when looking at a credits list or a log line for a film, are more enticing and intriguing to cinephiles than seeing the name Paddy Chayefsky’s name with a “Written By” credit next to it. Best known as the writer of the masterpiece that is Network, Chayefsky is one of the American stage’s greatest scribes, and in that has seen a fair share of his plays brought to the big screen. However, despite being one of the most influential writers of his generation, there are still a handful of films from the type writer of Chayefsky that have since become relatively unsung and forgotten.

One such film is a truly entrancing tale of love and loss, a brilliant little film entitled Middle Of The Night.

Based on his stage play of the same name, the film stars Fredric March as a lonely widower and influential clothing magnate who, despite the negativity coming from the support group of friends and family around him, falls head over heels in love with the much-younger bombshell, Betty Preisser, played by the ever magnetic Kim Novak. An employee of his, the relationship has more than its fair share of bumps in its romantic road, all attempting to examine these two people as they balance their emotional needs and a mighty large age gap.

Now, despite a tip top cast and director Delbert Mann behind the camera, this is truly the Chayefsky show, and his screenplay is so great, this truly becomes one of the most underrated romance dramas of the ‘50s.

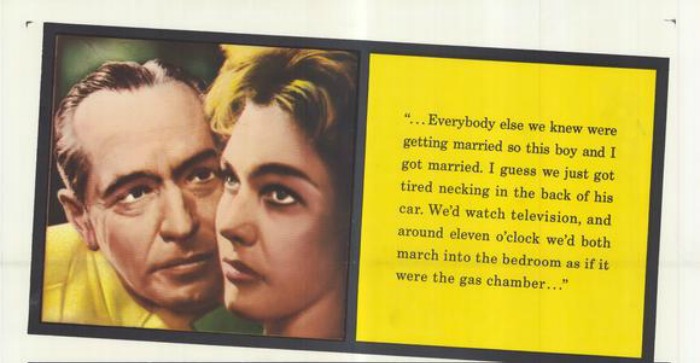

The greatness within Chayefsky’s screenplay is not only in its ability to paint these two leads as real, fleshed out characters with true and honest emotional needs and downfalls, but do so with as great a percussive sense of life and energy, that every word seems to pop off the screen. A truly verbose piece of work, the film takes this script’s breakneck verbal pace and turns it into a kinetic and lively look at love, loss and the meaning of it all.

It does also help that verbalizing this screenplay are two stand up legends of the big screen. Novak steals every scene here, taking a neurotic turn into youthful uncertainty, playing a recently divorced 20-something unsure about her lot in life but rather certain in her knowing that she longs to be truly loved. The lost soul opposite her; a rarely better Fredric March, oddly cast a Jewish businessman but none the less perfect in this performance, breathing a great sense of truth and angst into a character that is on the verge of an emotional break down following the death of his long time wife. A middle aged widower, the uncertainty behind the relationship at the film’s center is entrancing when given physical life by these two leads, and the peripheral familial discussions bring to light even more interesting relationship dynamics. Is this just a tale of a man looking for some vitality in the middle of his life, or are these two truly lost souls looking for some pure emotional solace in one another?

The supporting cast here is equally great, Martin Balsam and Lee Grant are particularly great here as Jack and Marilyn, March’s Jerry Kingsley’s son in law and daughter, themselves going through a great deal of romantic turmoil. Ostensibly the mirror of our lead romantic duo, the two are a couple deeply in love, but facing real, tactile relationship issues that seem to be in thematic step with the rest of the feature. Particularly during one scene near the end of the film, the pair really come alive and nearly steal the entire film right from under the noses of March and Novak. Tour de force supporting turns, these two help elevate this screenplay from great stage play to something truly cinematic.

But the real cinematic power comes from unsung filmmaker Delbert Mann. Mann, best known for his work during the “Golden Age Of Television” (as highlighted by Criterion in their box set of that same name, looking at his take on Chayefsky’s Marty), crafts a superbly intimate romance picture here, never allowing the viewer to get more than arms length away from the cast of characters. Getting the most out of some beautiful New York locations, this has the aesthetic trappings of a truly New York picture, and Mann never allows the film to devolve into what a narrative like this truly could, melodrama. Now, melodrama is not an inherently negative criticism, but with an aesthetic as naturalistic as this, it could raise the emotion to heights that it frankly doesn’t need to go, nor would feel proper for a film this personal. Mann’s a perfect filmmaker for this type of picture, and truly turns this into a film that should not be avoided for those with a penchant for energetic looks at love in all its possible stages.

And yet, it’s a film that is nearly impossible to find. Primarily available as part of Sony’s “Kim Novak Collection,” the film is in dire need of a warm and loving restoration, and with Criterion not afraid to look at this pertaining to the “Golden Age Of Television,” this creative team could be focused on rather deeply. Chayefsky’s work could itself support a deep and lengthy retrospective, and one would have to hope that Mann would get the supplemental discussion he truly deserves. Toss in an appreciation from a TV director working today, and you have a release that could really be a superb and intriguing edition of one of the most underrated dramas of the ‘50s.

![Bergman Island (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/bergman-island-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/this-is-not-a-burial-its-a-resurrection-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![Lars von Trier's Europe Trilogy (The Criterion Collection) [The Element of Crime/Epidemic/Europa] [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/lars-von-triers-europe-trilogy-the-criterion-collection-the-element-of-400x496.jpg)

![Imitation of Life (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/imitation-of-life-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (The Criterion Collection) [4K UHD]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/the-adventures-of-baron-munchausen-the-criterion-collection-4k-uhd-400x496.jpg)

![Cooley High [Criterion Collection] [Blu-ray] [1975]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/cooley-high-criterion-collection-blu-ray-1975-400x496.jpg)