With the calendar indicating that my next step in the Journey Through the Eclipse Series was due to publish on Valentine’s Day, it seemed pretty obvious that the occasion called for something romantic for our next selection. However, that lighter, sweeter, fluffier stuff is not the strong suit of the Eclipse line, and I recently used up one of my best sources for that kind of material when I wrote about Ernst Lubitsch’s The Love Parade a few weeks ago. So I scanned the list of titles and came up with something that seemed to fit: Love Affair, or the Case of the Missing Switchboard Operator, from Eclipse Series 18: Dušan Makavejev Free Radical.

Even though I’m just beginning my acquaintance with Makavejev’s work (and his name, by the way, is pronounced so as to rhyme with baseball Hall of Famer Willie McCovey, with an extra ‘ev’ tacked on the end), I really enjoyed Innocence Unprotected, reviewed here last year. I know enough about his overall cinematic reputation (outlandish political satire infused with confrontational visual imagery and ruminations on human psycho-sexual impulses) that I figured any film of his titled Love Affair would have something interesting, maybe even arousing, to say on the subject.

Of course, I was focusing a lot more on the first two words of the film’s title instead of the subordinate phrase. If I had given the alternate a bit more thought, I might have kept on looking, since it implies a person who’s disappeared, and that implies a death under mysterious circumstances, such as, say, murder. Which, depending on how it’s portrayed, tends to deflate the sensual glow that a Valentine’s Night movie selection usually attempts to kindle. At least in my experience. Your mileage may vary.

But I’d already made my choice, so I stuck with it. Sure enough, we learn early on that Izabela, the cute, flirtatious Hungarian phone attendant, meets an untimely demise, though it’s not initially explained why. Somehow her fate is tied to a hook-up she had with Ahmed, a middle aged, shlumpy rat exterminator. But Makavejev isn’t really telling the story of an affair here – he’s working in that late 60s Godardian idiom, weaving traces of narrative with documentary-like interpolations, creating what turns out to be a short (68 minute) movie. It feels like there’s as much extraneous non-fictional material (some of it borrowed from other filmmakers) in Love Affair as the usual ‘actors advancing a plot.’ And then when it comes to editing, the chronology is all over the place, so that we’re jumping back and forth between scenes that take place early and later on in the relationship.

Love Affair opens with one of those documentary bits, a monologue by an elderly ‘medical sexologist’ who provides a flimsy academic rationale for the nudity and casual explicitness of what is soon to follow on screen. Though Makavejev was on a path to get into much bigger trouble for much more graphic portrayals of sexual behavior on screen in years to come, I figure Love Affair was provocative enough in its time (1967) to stir up controversy, especially in a society like Yugoslavia, under Communist rule and wrestling with the same between authoritarianism and free expression that were then taking place all across Europe and North America.

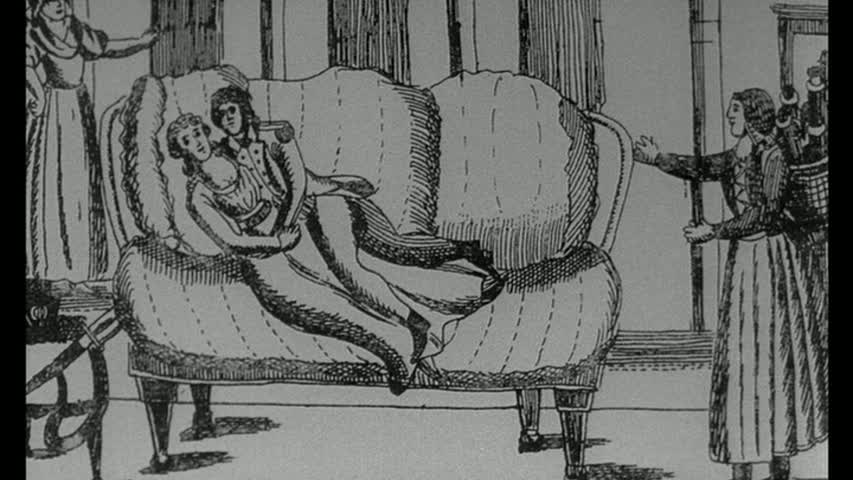

The good doctor ushers us into Makavejev’s world by giving a short discourse on the long history of sex rituals and phallic worship that has, for the most part, been repressed and relegated to the outermost margins of our cultural heritage over the centuries, largely due to religious taboos and the social mores that grow out of them. Some fascinating (and NSFW) images pop up on screen, clearly showing their antiquity, as the professor drones on. Here’s one that’s modest enough to share without jeopardizing anyone’s job security:

Belgrade street scenes show a city going through reconstruction, filled with crowds of pedestrians, juxtaposing the whispered chatter about sex mentioned to by Dr. Kostic in his opening statement with patriotic hymns urging Yugoslavian workers to take pride in their collective achievement. Makavejev’s camera follows Izabela on her perambulations, showing off her suitably proletarian but agreeably clingy wardrobe of sleeveless dresses and allowing her natural sexiness to come through without drawing excessive attention to her attributes. She’s a likeable character, possessed of no particularly strong ambitions – just another young person who’s in the process of figuring out what to make of her life. Which unfortunately has much less time left in it than she would ever suspect until it was too late.

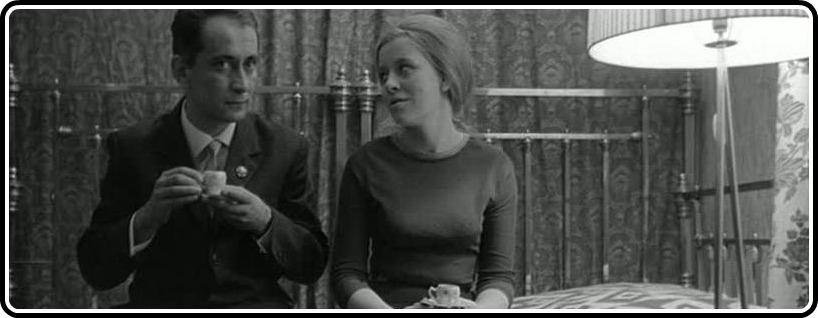

Ahmed (who brings to mind, I can’t help it!, a younger, paler John Boehner) is a play-by-the-rules, nondescript fellow who practically stumbles into his relationship with Izabela. He’s probably close to 20 years older than her, and seems initially to be a bit dumb-founded as to how or why a guy like him could make it with a modern girl like Izabela. The basic explanation is that she and her friend Ruzica were just feeling horny and were thus on the lookout for men they thought capable of satisfying their desires. She took him for an official who ranked higher than he really does on the social(ist) ladder, but they both have something to offer each other. This clip shows a few glimpses of their relationship at its peak, and also nicely demonstrates Makavejev’s subversive audio-visual wit:

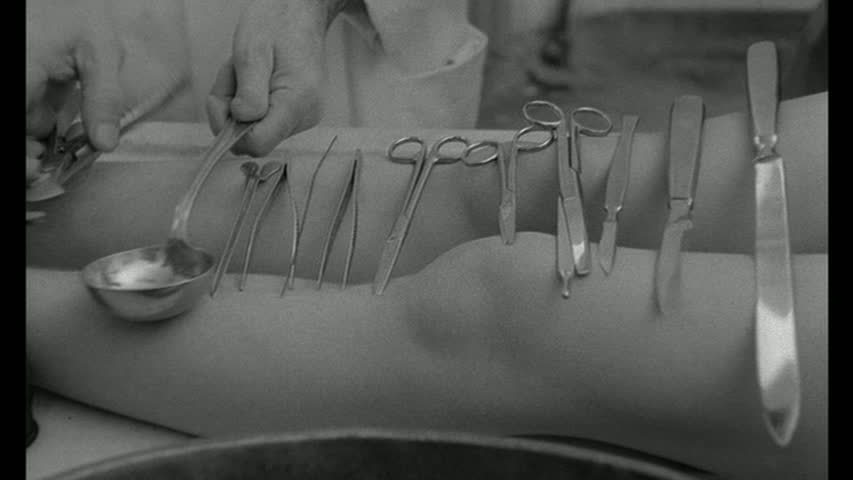

That pleasant little interlude is framed by some unflinching looks at the hard realities of life: short procedural bits on the retrieval of corpses, gathering and analysis of criminal evidence in homicide investigations, autopsies, the centuries-long war between man and rat, plumbing fixtures gone awry and other similarly grim matters.

Makavejev tosses in true-to-life touches like boiling coffee on the bottom of an upturned iron (because the stove is broken) and watching old propaganda films featuring the overthrow of the Romanov dynasty on Yugoslavia’s state-run TV network as the night’s entertainment prior to climbing into bed for humorous digs at the political regime.

As Love Affair fatalistically wends its way to the tragic circumstances that bring about its end, Makavejev continually throws in ironic surprises in his collage of found footage that barges in on viewers at crucial strategic moments. Though he fits quite naturally into that late-60s fad of throwing random crap together as an affront to cinematic and cultural tradition, there’s enough substance and imagination offered to overcome the dated frivolity of similar exercises from that era. And at just over an hour in length, this is a Love Affair that doesn’t wear out its welcome or demand excessive concentration from the audience, even with its skewed timeline.

Here’s another aspect of what makes Love Affair a cool old movie – its versatility (and relative lack of copyright-enforcing authorities hovering nearby) as a source for music video material. I found this nice tribute to what Makavejev himself practiced, reconfiguring other people’s material for his own purposes. It’s a homemade mash-up of a Mercury Rev song and scenes from Love Affair – a rather charming combination.

Consider it my online Valentine to our loyal Criterion Cast readers! The clip communicates the joy and freedom to be found in Makavejev’s original film, while setting The Case of the Missing Switchboard Operator aside to be investigated some other time. For tonight at least, let’s just focus on the love. <3

![Bergman Island (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/bergman-island-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/this-is-not-a-burial-its-a-resurrection-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![Lars von Trier's Europe Trilogy (The Criterion Collection) [The Element of Crime/Epidemic/Europa] [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/lars-von-triers-europe-trilogy-the-criterion-collection-the-element-of-400x496.jpg)

![Imitation of Life (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/imitation-of-life-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (The Criterion Collection) [4K UHD]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/the-adventures-of-baron-munchausen-the-criterion-collection-4k-uhd-400x496.jpg)

![Cooley High [Criterion Collection] [Blu-ray] [1975]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/cooley-high-criterion-collection-blu-ray-1975-400x496.jpg)