Last week I was poking around in the MUBI.com Forum, as I’m inclined to do whenever I’m curious to see what fellow cinephiles are chatting about at any given moment, when I happened to see this thread, titled March 7: Chantal Akerman. Though nothing much occurred in the thread, the synchronicity of my random discovery and my need for some kind of direction as to what Eclipse film I would review on March 14 was sufficient to lead me to this week’s choice. It’s je tu il elle, from Eclipse Series 19: Chantal Akerman in the Seventies.

I went into my viewing of je tu il elle (I You He She, for those of you still honing your basic French 101 skills) relatively blind to what I’d encounter. I knew a bit about Akerman’s work, mainly from last fall’s review of her New York Films (timed around remembrance of the events of 9/11/01) and the notoriety generated by her most famous film Jeanne Dielman, 23, Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles. So I knew to expect long static shots, minimalist approach to plot exposition, a strong avant garde and young feminist sensibility and practically none of the trappings of what one comes to expect from cinema with commercial aspirations of any sort. I decided not to do much reading up on the film in advance either, even postponing my look at the liner notes until I had given je tu il elle as clean of a slate to make its impressions upon me as possible.

I’m glad that I did! That approach helped preserve some of the initial challenge and I might even say shock that Akerman must have had in mind when she conceived, wrote, directed and acted in her first feature-length film. Je tu il elle followed Le Chambre and Hotel Monterey, the two earliest New York films and preceded Jeanne Dielman and Letters from Home (the third and final New York film.) That’s helpful information to keep in mind when sizing up the impact Akerman achieved here, as is the fact that she was only 23 years old when she shot this largely self-funded project back in the early 1970s. Some of the innovations in je tu il elle may seem bland, obvious or passe in our era of narcissistic self-absorption, YouTube ubiquity, wide-scale public and private exhibitionism and the ease we enjoy nowadays of just setting up a camera and filming whatever ideas or impulses come to mind. Things were different back in 1975. Of course, any film viewed in 2011 has to justify itself in terms of today’s cultural aesthetic in order to be relevant, unless one is conducting strictly historical research. I think je tu il elle, while not likely to hold the attention of your “average” film fan, delivers enough in its intelligence and audacity to hold our attention, despite the slow, drawn out pacing and a hesitancy to forge obvious emotional connections with the audience. Akerman’s work provided a vital influence in opening our culture up to low-budget, straight-on point & shoot self-disclosure as a key element of contemporary independent cinema, whether with today’s convenience of portable high-quality video imaging or the more deliberate and cumbersome production planning associated with film.

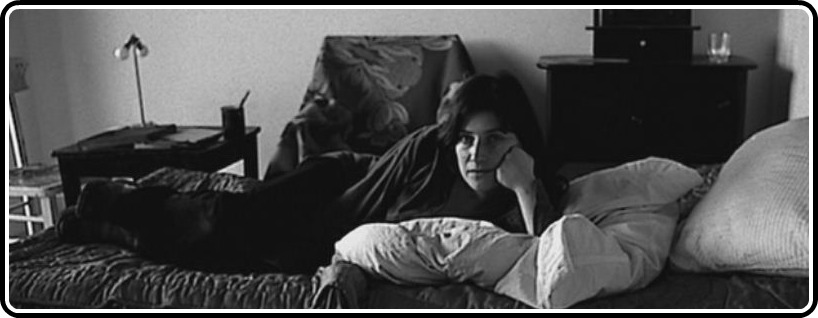

Still, as intrigued as I was with je tu il elle, I think it’s necessary to emphasize that this isn’t an easy film to enjoy, nor is it meant to be. Akerman was obviously a young woman with a lot on her mind; though I know better than to draw uninformed conclusions about how strictly autobiographical this or any other film may be, it’s likely that the obvious themes of alienation, loneliness, relational confusion and general dissatisfaction with the life options at one’s disposal were fairly close to Akerman’s heart at this time. And why not? The early 20s tend to be pretty tumultuous years, especially in those possessed of a restless, creative temperament. And that’s clearly true of Julie, the character we meet and follow throughout je tu il elle, with her back turned to the camera, speaking in mid-sentence to someone other than us.

Julie has just gone through a break-up, and she’s isolated herself in a makeshift apartment, probably furnished with someone else’s belongings. The first third of the film (and it follows a classic three-act structure) consists of Julie fretting about how to manage her feelings and decide what to do next. She moves furniture around. She writes letters, multiple drafts of the same thoughts, over and over, apparently obsessed with getting it all out just right or frustrated at the inability of putting words on paper to trigger the catharsis she needs. She strips off her clothes and wanders around her emptied out rooms in the dark, perhaps seeking a return to a primal state in order to clear her head. There’s no indication that drugs had anything to do with this eccentric behavior, which lasts for several days of confinement in the apartment, with just occasional glances out the window. But it was the early 70s, I lived through that era, I know what was going on, I have to at least ask the question. Her diet consists of spoonfuls of powdered sugar from a brown paper bag, which she eventually spills on the floor, then patiently spoons up to put back in the bag (and we get to see every bit of that action.) She’s stressed out, she’s not healthy, she has no idea what to do next.

Now a different, more conventional story-teller could go down the analytical rabbit trails, wondering about a possible need for psychiatric intervention, or perhaps take the more common sense approach and prescribe nothing more exotic than a good old-fashioned job or husband for this pampered, over-indulged artsy rich kid. But this is Akerman’s movie and no major studio or marketing genius got their hands on this film, thank God, so she’s able to tell a more authentic story in a more interesting way.

After coming close to exhausting all the possibilities of what she could accomplish in the apartment, Julie/Akerman sets out on a road trip, of the hitchhiking variety. Julie takes a ride with an unnamed trucker, a young handsome guy who initially seems pretty indifferent toward his passenger, though he does treat her to a badly needed meal along the way. The scene in that diner is one of my favorite in the film simply because of the amusing interpolation of action-movie soundtrack music playing on an unseen TV as the static pair wordlessly stuff their mouths with food.

After they get to know each other, their ephemeral connection warms up just a bit. He takes her to a favorite bar, they have a beer, then it’s back in the truck for some late-night AM dial channel-surfing, another bar, another beer, a quickie her-to-him off-camera hand job as they pull off the freeway, an unpretentious rundown of the driver’s chauvinistic philosophy regarding sex and marriage, and finally a quick shave as he nears his destination and the two of them go their separate ways. As trivial and superfluous as it may seem, the shaving scene is important for no other reason than the demonstration of Julie’s intense, penetrating gaze as her companion goes through his mundane routine – it’s indicative of how closely she (and no doubt Akerman) scrutinizes all the small things of life, seeking out the patterns and connections that give it meaning.

We then learn that Julie wasn’t hitchhiking just to get any old place – she had a destination in mind, and her ride with the trucker, while significant for its own sake, was more just a means to an end. And that end is a reunion with a girlfriend, the one she apparently left when je tu il elle first began. Julie arrives unexpectedly, surprising her (also unnamed) friend. She requests food, having lived on little more than sugar and beer for several days now, and afterward, nourishment of a more carnal sort.

The build-up to the lovemaking scene that constitutes the final 20 minutes of the film is nearly wordless but fascinatingly complex, with each woman sending ambivalent signals of desire, anxiety, reluctance and compassion through small gestures and facial expressions. Who’s using, who’s rejecting who in this scenario? A subtle clash of wills is taking place here, but it’s nearly impossible to determine who is doing the seducing. As if that matters anyway.

The sexual interaction between Julie and her girlfriend is pretty explicit, though not by the standards prevalent in 21st century pornography (or even 20th, for that matter.) Though there are a few cuts and changes of camera angle throughout the scene, the lens maintains a spectatorial distance, and there’s no effort made to arouse the voyeuristic tendencies of the audience. While the women go at it with a lot of energy and youthful vigor, the exchange is like wrestling than passionate ecstatic pleasure. In other words, it’s more like how people really look and act when they make love without the coaching or incentives associated with professional sex-on-film. The session ends with them quietly embracing, asleep until dawn, when Julie gets up and makes her way back out into the world, her cravings for food and sex satisfied, temporarily to be sure, but perhaps just a little less neurotic now as a result of the encounter.

A filmmaker like Akerman, brimming with intelligence and bold enough to put forth an uncompromising aesthetic for the sake of her art, is exactly the type that compels the admiring cinematic intelligentsia to outdo themselves in their lexicon-busting reviews. A few examples, like this one and this one and especially this one handily prove my point. While I can appreciate some of the insights these writers manage to convey through their weighty prose, I won’t go so far as to assume that even those who find films like je tu il elle to be worth the extra measure of work asked of us will feel similarly transported to such heights of intellectual stimulation. Though the tonal differences between Akerman’s work and the nascent mid-70s punk rock scene are obvious, I also detect a similar attitude of rawness, of a (then) younger generation developing its own voice contrary to the 60s era filmmakers who preceded them while selecting certain threads of that tradition to carry forward. Mostly though, especially at this point in history, I see Akerman as a forerunner, and je tu il elle as a significant breakthrough work that helped establish a lot of today’s less stage-driven visual vocabulary. This video, featuring a soundtrack of Charlotte Gainsbourg (female lead in Antichrist) singing “5:55”, uses footage from je tu il elle. Compare this fan-made video with Gainsbourg’s studio produced original promo, and notice how the similarities demonstrate just how smoothly Akerman’s progressive mid-70s aesthetic makes a successful, non-retro transition to pop media nearly four decades later.

![Bergman Island (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/bergman-island-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/this-is-not-a-burial-its-a-resurrection-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![Lars von Trier's Europe Trilogy (The Criterion Collection) [The Element of Crime/Epidemic/Europa] [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/lars-von-triers-europe-trilogy-the-criterion-collection-the-element-of-400x496.jpg)

![Imitation of Life (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/imitation-of-life-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (The Criterion Collection) [4K UHD]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/the-adventures-of-baron-munchausen-the-criterion-collection-4k-uhd-400x496.jpg)

![Cooley High [Criterion Collection] [Blu-ray] [1975]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/cooley-high-criterion-collection-blu-ray-1975-400x496.jpg)