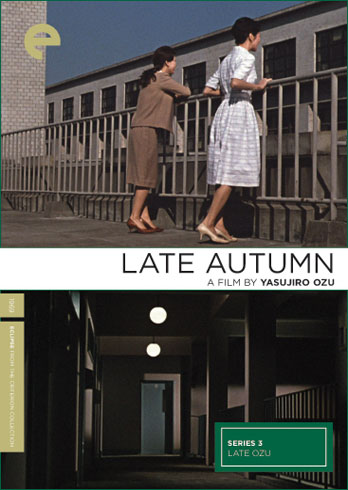

As 2011 draws near to its end, so also my personal endeavor to blog my way chronologically through the Criterion Collection is close to finishing up the films of 1960. Released in mid-November of that year, Yasujiro Ozu’s aptly-titled Late Autumn is among the very last 1960 titles found on my comprehensive timeline of all Criterion-related films, with only Kapo (an Essential Art House exclusive) and The Naked Island (currently streaming on Hulu Plus) left for me to watch, along with one Stan Brakhage short, The Dead, that I wrote about this morning on my Criterion Reflections blog.

Among Ozu’s work, Late Autumn brings us rather close to the end of that great director’s career; he only made two more films after this one. Even though the specter of death is only indirectly invoked, in that two of the film’s main characters are widowed, having lost their spouses several years earlier, viewers who track Ozu’s development can clearly sense his awareness of mortality and contemplation of the unstoppable passage of time that informed his work at this late stage. Late Autumn is the third consecutive film that Ozu made, following Good Morning and Floating Weeds, in which he revisited plot lines from some of his earlier (and greatest) movies. In this case, Ozu didn’t reach as far back into his silent era as he did in the two previous pictures. Late Autumn incorporates the basic narrative device of his first postwar classic, Late Spring, released in 1949 during the waning years of the American military occupation of Japan. In both films, a daughter considered overdue for marriage resists the efforts of those around her to arrange a suitable spouse for her, preferring to stay in the household of her widowed parent and frustrated that social customs won’t accept her desire to remain independent and in a comfortable living arrangement. In order to give the daughter a nudge toward matrimony, the parent tentatively accepts a suitor’s proposal for marriage, upsetting the domestic equilibrium while simultaneously forcing and permitting the faithful daughter to go ahead, get married and move out herself. No stopping the forces of change, after all.

The twists with Late Autumn are that here, the widowed parent is a financially self-reliant mother, rather than Late Spring‘s father. Even more significantly, the great Japanese actress Setsuko Hara, who played the daughter Noriko in Late Spring, now takes on the parental role of Akiko, a casting decision far from coincidental that adds rich layers of poignancy for admirers of her superb, compassionate screen presence.

But before I get to further summary and commentary on Late Autumn‘s action, let me just begin with the film’s opening establishing shots, of a large structure with architectural features that remind me of the Eiffel Tower, whether or not it was intended to draw such comparisons. My first glimpse of it got me thinking about Zazie dans le Metro, the most recent film I wrote about on my blog. Other than that both films were released in November 1960, were shot in color and had a soundtrack, there is absolutely nothing else beside the tower imagery that Late Autumn has in common with Zazie dans le Metro.

A significant challenge facing any reviewer of Ozu films from this stage of his career is to do sufficient justice to the mature beauty and elegance of his style that he so fluently demonstrated. The trailer, embedded above, offers one commercially-minded take on Late Autumn, and it’s a fair assessment, though it barely scratches the surface of what makes this such an impressive work. A simple synopsis of what happens in their respective stories runs the risk of making the Late Ozu films sound simplistic, uneventful, maybe kind of boring. Even Late Autumn‘s status as a “remake,” of one of Ozu’s most fondly regarded films no less, could generate a somewhat indifferent response from those who tend to demand more in the way of novelty and sensory stimulation from their movie watching pastimes. While it’s true that Ozu doesn’t really break new ground here, the gratification comes from watching a master refine his art to the point of sublime near-perfection as he clarifies his vision, discovering new heights of purity that he’s able to share with those of us who’ve followed along with the development of his craft up to this point.

Clearly knowing that most in his audience had already established some familiarity with both his unique directorial style and the impressive cast of regulars he frequently collaborated with, Ozu builds on that prior acquaintance by quickly introducing two of his most beloved performers, Chishu Ryu (the father in Late Spring and so many other Ozu masterpieces) and Setsuko Hara, who was nearing her own retirement from cinema as well. Her next appearance, in Ozu’s The End of Summer (1961), would be her last, even though she’s still alive today, over fifty years later.

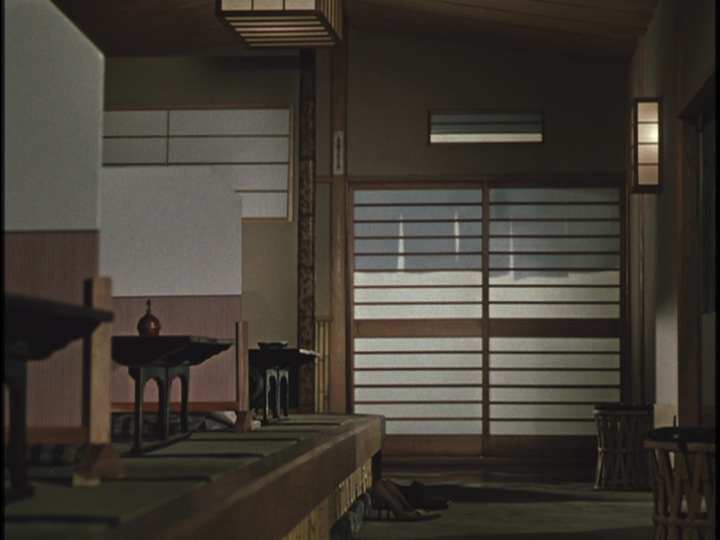

As important as the actors are, Ozu’s distinctive use of interior spaces is every bit as crucial. The lines, the lighting, the discreet placement of objects around the perimeters and in the forefront of his frames… these technical details seem like eccentricities to the novice, but become sources of a peculiarly comforting form of inspiration as we allow ourselves to be drawn into the environments Ozu presents on the screen. And his characters, typically offering little in terms of demonstrative agitation, so measured in their response to whatever’s happening around them, quickly come to feel like old friends after we’ve spent some time in their company and begin to see the world through their eyes. Late Autumn’s middle-aged businessmen are our tour guides through particular foray into Ozu’s world, a trio of slightly emasculated busy-bodies who presume their self-importance on the surface, while quietly recognizing that Japan is no longer the unquestioned “man’s world” that their forefathers once took for granted.

But before I go off the deep end with highbrow acclaim for the venerable Ozu, keep in mind that the old master wasn’t above taking advantage of the commercial potentials offered by strategic product placement. (Memo to Ryan: do you want me to contact Johnnie Walker Scotch or Sapporo Beer to see if they’re interested in doing some sidebar ad business with us?)

While the similarities between Late Autumn and Late Spring, in both general plot and specific details (romance initiated on a rural hiking trip, an argument between friends that brings an overnight visit to a premature end), are intriguing, the differences between the two films shed substantial light on Japan’s progress in rebounding from the war over the course of a mere decade. Late Spring‘s milieu feels pretty rough and improvised, with vestiges of traditional Japanese culture (the Noh performance) somewhat awkwardly co-existing with indications of the American presence (the Coca-Cola sign that Noriko passes on her bike ride.) By the time of Late Autumn, Japan has settled into a course of accelerating Westernization, with middle-class prosperity softening the edges of despair, though not able to entirely fill the emotional empty spaces that exist between and within us. Accompanying this recently-secured affluence is an new and somewhat unprecedented acknowledgement of the voice of young people. One of Late Autumn‘s most memorable and effective scenes, quoted briefly in the trailer clip above, shows the three businessmen, each presumably successful and respected in their professional endeavors, enduring an embarrassing tongue-lashing from Ayako’s friend Yuriko. She reprimands them for spreading rumors that temporarily strain the relationship between Akiko and her daughter – another reminder that the foundations of society have shifted and would continue to do so as the callow youth of Japan’s “sun tribe” subculture continued to enter adult society at the dawn of a new decade.

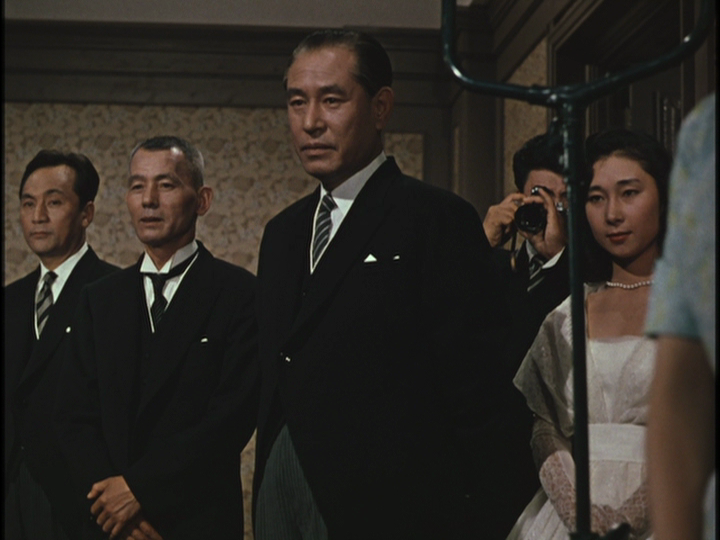

Another fascinating point of comparison between Late Autumn and two earlier Ozu films in which the arranged marriage of a female protagonist played a crucial part is how the director increased his willingness to put at least some of the wedding festivities on the screen. In Late Spring, the wedding between Noriko and Satake is not shown at all; in fact, we never even see the groom. In Early Summer, from 1951, we only see the groom in a photograph, and even in that, we don’t get a clear look at him. Here, we not only get to know the groom, but he seems like a pretty solid fellow, one that Ayako has a reasonable chance to find happiness with and with whom the audience can positively identify. Perhaps Ozu, who never married himself and lived with his mother for most of his adult life, was warming up to the necessity of marriage as a social institution in his later years.

Whatever Ozu might have thought about the way marital relationships were handled in Japan as it transitioned away from the tradition of arranged marriages to more romantically-based couplings, it’s clear that he’s not as averse to depicting the event in a more positive light than he had in his earlier films.

The rituals surrounding the official wedding portrait are given a sympathetic treatment, even though we never get to see the newlyweds after the ceremony takes place. Ayako and Goto are, for all intents and purposes, sent on their way, or one could even say cinematically embalmed, so that the focus can return to the leftover, the survivor, the parent who made one last sacrifice for her daughter… Akiko.

This last clip shows the final evocative scenes from Late Autumn. Though it could plausibly be regarded as a spoiler, I don’t think it’s giving much away to reveal that after Ayako’s wedding, Akiko finds herself left alone in her apartment, contemplating the bouts of loneliness that she will inevitably have to face in years to come. Again, a mere description of the event hardly begins to communicate the wisdom and insight with which Ozu composes these scenes. But just as one would probably do better to start their exploration of Ozu’s films with his middle period works like the Noriko films (Late Spring, Early Summer, Tokyo Story), or even better yet, go back to his surviving silent films and work forward from there, it’s probably best that the clip be viewed by those who’ve seen Late Autumn at least once already, and know enough about Akiko’s situation to properly enter into and respect the dignity of her solitude.

![Bergman Island (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/bergman-island-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/this-is-not-a-burial-its-a-resurrection-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![Lars von Trier's Europe Trilogy (The Criterion Collection) [The Element of Crime/Epidemic/Europa] [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/lars-von-triers-europe-trilogy-the-criterion-collection-the-element-of-400x496.jpg)

![Imitation of Life (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/imitation-of-life-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (The Criterion Collection) [4K UHD]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/the-adventures-of-baron-munchausen-the-criterion-collection-4k-uhd-400x496.jpg)

![Cooley High [Criterion Collection] [Blu-ray] [1975]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/cooley-high-criterion-collection-blu-ray-1975-400x496.jpg)