With the onslaught of talking pictures hitting as we entered the 1930s, many people (directors, producers, etc) deemed the silent film dead on arrival. However, with Charles Chaplin firmly in production on what has become one of the director’s most beloved entries, City Lights, as the talking picture came into power, one of the greatest movie stars of all time took to the big screen for not only a breathtaking new comedy picture, but a damning turning up of his nose at the idea that film needed anything more than scarce title cards, and a cast with an affinity for pantomime.

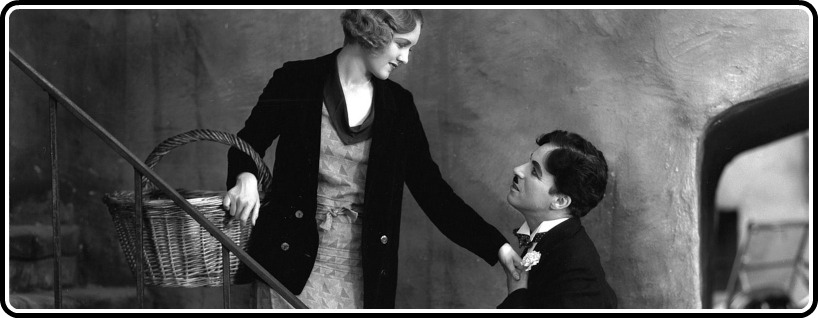

City Lights, one of Chaplin’s most devastating and emotionally resonant pictures, tells the story of Chaplin’s legendary Little Tramp, only this time, he’s got a flower girl on his mind. When he meets this blind flower girl (played by the ever wonderful Virginia Cherrill), his life completely changes, and it only changes further when he takes up the guise of a millionaire to woo this woman. Then, when he encounters a suicidal millionaire only to save him from committing that horrible act, he sparks a friendship with the drunkard. However, when the man sobers up, he barely knows The Tramp, and with an eye surgery that could change the entire relationship he holds with his new love interest, Chaplin’s legendary character must learn to deal with not only a changing world, but that appears to be entirely conditional.

But what is not conditional is Chaplin’s power behind the camera here. Featuring some of the most expressive camera work you’ll find in a Chaplin film from this era (or ever, for that matter), this black and white masterpiece is truly one of the greatest cinematic achievements in Chaplin’s canon. From the free-flowing camera as we make our way across a dance floor during a party or the film’s heart-shattering finale, the film finds Chaplin the director at his most mature, his most experimental and his most provocative.

As seen from the very beginning, Chaplin is not only painting an emotionally powerful piece of cinema, but a proverbial middle finger to all of cinema, a cinema that seemed at the time to see silent cinema as a dead entity. You see from the opening sequence that Chaplin is as interested in telling a romance tale as he is throwing pie in the face of a world of sound films that he sees as nothing more than squeaks and squawks. This, along with his breathless handling of tones here, jumping from the brazenly slapstick to the previously mentioned wallop of a final sequence (still one of the most emotionally resonant finales in all of film), proves that Chaplin was a master not only of physical comedy, but being able to turn that comedy into a level of emotional connection and resonance that has never been reached again.

Performances here are as thrilling, as well, as anything Chaplin would put on screen. The Tramp takes center stage for the final time, and in what may be the character’s crowning moment. A story so involved with his view of the world, the loveable character is completely embodied here by Chaplin, who is at the height of his physical comedy powers with this masterpiece. Chaplin is perfect here as The Tramp, showing off not only his skill at selling truly gut busting physical comedy, but his ability to, without a single word or little more than a title card, tell a story with his face and emotions. A towering turn for the legend, this may be the single greatest performance he’d ever give. Cherrill is equally great here as the flower girl, but really comes into her own with a final scene that will forever be burned into the mind of whoever views the picture. Cherrill and Chaplin have perfect chemistry together, and, especially in that final scene, both have faces built to really mine silent film for all it is worth emotionally.

Now, while it goes without saying that the film is not only a classic romantic comedy but also a thrilling bit of spit thrown right in the eye of sound cinema, what hasn’t had the time to be talked about is Criterion’s new switch to Dual Format releases. One of the first of this new release structure, the dual discs are beautifully packaged here, both with gorgeous artwork (which is stunning throughout the entire release, particularly the spine, which I’ve fallen quite in love with) and are structured within the case to make the most of the Blu-ray jewel case. The release itself features a stunning 4k restoration which really pops off the screen. Jeffrey Vance’s new commentary is a must listen for fans of Chaplin’s picture or just cinema in general, and the series of interviews, archival footage and even some boxing footage from his short The Champion really add a lot of depth to the release as a whole.

The boxing footage is of particular note here, as it gives a really good insight into what is a huge inspiration for one of the most interesting gags in all of Chaplin’s canon. There is a boxing set piece found within this full picture that is easily one of the most inspired comedic scenes ever shot, and as historian Vance points out, proves that this is as melancholy a picture as Chaplin would craft. With a Tramp that doesn’t find a winning moment, really, throughout the picture, the boxing sequence is not only a tour de force aesthetically, but one of the most interesting sequences in all of silent comedy.

Overall, this is yet another A+ release from Criterion that proves this legend’s filmography could not have been put in better, more loving and caring hands.

![Bergman Island (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/bergman-island-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/this-is-not-a-burial-its-a-resurrection-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![Lars von Trier's Europe Trilogy (The Criterion Collection) [The Element of Crime/Epidemic/Europa] [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/lars-von-triers-europe-trilogy-the-criterion-collection-the-element-of-400x496.jpg)

![Imitation of Life (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/imitation-of-life-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (The Criterion Collection) [4K UHD]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/the-adventures-of-baron-munchausen-the-criterion-collection-4k-uhd-400x496.jpg)

![Cooley High [Criterion Collection] [Blu-ray] [1975]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/cooley-high-criterion-collection-blu-ray-1975-400x496.jpg)