Interpersonal relationships, particularly that of the married variety, are some of the most mined themes and topics in all of film history. Be it as the ground work for entire movements like cinema verite (Alan King’s A Married Couple is both a definitive time capsule of social change and also a touchstone of the start of this movement) to the entire basis for directorial careers like that of Woody Allen, marriage has been portrayed on screen in as many ways as one could possible imagine.

However, very few have touched the searing realism of a film like John Cassavetes’ Faces.

Arriving just about a decade after his now iconic debut feature, Shadows, Faces is a decided departure for the filmmaker, a breathlessly realistic picture that finds Cassavetes a more mature craftsman, and ultimately, a director who crafts one of the greatest and most beautiful pieces of human drama ever put to celluloid.

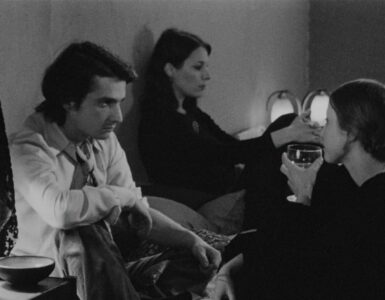

Shot in a disturbingly high contrast 16mm, this meditation on a marriage completely disintegrating stars the pair of John Marley and Lynn Carlin as a husband and wife duo on the verge of a complete breakdown. We meet the pair, Richard and Maria, as they attempt to find ways out from under a crumbling marriage with the help of a few new acquaintances. Taking all of the raw energy and emotional realism that made his debut feature the groundbreaking American independent feature that it would become, and finds as dramatic an evolution aesthetically as you’ll find in any director.

Yes, this wasn’t Cassavetes’ second film, but after a handful of serviceable studio pictures (the best of which is likely A Child Is Waiting) and some TV work, it was this, a film debuting nine years after his first feature, that is one of his most legendary, and his most aesthetically breathtaking. Employing all the claustrophobic close ups, all the eye popping black and white photography and a hazy 16mm-aided aesthetic that makes Shadows a great film, this picture takes all of those things to the next level. With each grain of film bringing with it a palpable sense of vitality, this blazing meditation on a marriage and its decline holds within it single frames that are as heart stopping as the prettiest tableaux. A definitive American independent feature, the film’s inherent sense of energy not only bleeds out of its performances, all of which are top tier, but primarily out of the camera work of one John Cassavetes. Seemingly a blood brother of films like the aforementioned verite classic, A Married Couple, this brazenly vital, fly on the wall type marriage drama is as palpable and lively today as it has ever been, and it is a testament to the timeless direction of Cassavetes that this is true. Often times in your face and ostensibly melodramatic, the film’s improvisational aesthetic (both via Cassavetes behind the camera and the performances he shoots in front of him) breathes a stirring sense of tactility into the picture, particularly in many of the opening sequences, the most breathtaking of them being a powerful conversation between our lead husband and wife in their house.

And speaking of the two leads, they give two truly haunting turns. Finding much of their respective performances shot in stark close up, these two performances are primarily powered by the breathlessly expressive faces of leads Marley and Carlin. Itself an extremely jazz-influenced picture, these improv-heavy turns bring that comparison to new heights. Feeling like two musicians riffing off the performances of one another, these two turns prove that Cassavetes was just as interested in crafting a realistic picture as he was in building a narrative that feels ripped right out of the actual lives of everyone involved. These two lead turns are ostensibly extensions of the aesthetic trying to be pushed forward by the auteur behind the camera, and they are both absolutely unforgettable. Toss in turns from future Cassavetes regulars like Seymour Cassel and Gena Rowlands, both portraying the two people our leads find solace in, and you have a film that is claustrophobic, intense and more often than not oppressively melodramatic, but also a film that is utterly masterful.

And this may also be one of Criterion’s most impressive restorations. Following the top notch restoration of Cassavetes’ Shadows comes an even more entrancing restoration that will ultimately leave any viewer reaching for their remotes, just to pause and stare in awe of what Criterion has done with this brilliant Cassavetes picture. With each frame holding within it as much energy as the next, this is a must see film for anyone that thinks that film has lost reason to exist, each frame an awe-inspiring tableaux more beautiful than the last. Supplements here include an alternate opening sequence running 18 minutes in length, a episode of the French show Cineastes de notre temps dedicated to Cassavetes, and a trio of documentaries looking at the making of the film, and also two looking at the actual production of the film, focusing on the work of Al Ruban. The second part of Criterion’s must-own John Cassavetes: Five Films box set, this is just one of five reasons that this box may very well be the greatest box set Criterion has ever put together.

Next we talk about arguably Cassavetes’ best known film, A Woman Under The Influence.

![Bergman Island (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/bergman-island-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/this-is-not-a-burial-its-a-resurrection-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![Lars von Trier's Europe Trilogy (The Criterion Collection) [The Element of Crime/Epidemic/Europa] [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/lars-von-triers-europe-trilogy-the-criterion-collection-the-element-of-400x496.jpg)

![Imitation of Life (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/imitation-of-life-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (The Criterion Collection) [4K UHD]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/the-adventures-of-baron-munchausen-the-criterion-collection-4k-uhd-400x496.jpg)

![Cooley High [Criterion Collection] [Blu-ray] [1975]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/cooley-high-criterion-collection-blu-ray-1975-400x496.jpg)