Opening up with a beautifully quiet sequence introducing us to our lead character, an elderly woman named Oharu, director Kenji Mizoguchi not only brings to light a character whose life we will be ostensibly following from a teenage love affair all the way to her current state nearing the end of her life, but proclaims to the viewer that this is a film that itself may weigh heavy on their backs for long after.

However, nothing, and this writer stresses that nothing, can prepare a viewer for the potent and powerful drama that follows for the film’s oddly taut 146 minute runtime.

A startling meditation on gender issues in Edo period Japan, Mizoguchi’s The Life Of Oharu tells the tale of Oharu, a woman who we meet during the final stage of her life. As she begins to see the men who have made an impact in her life in the faces of statues in a temple, we are told her story in a series of episodic flashbacks.

Encompassing various decades, Oharu is played by the ever breathtaking Kinuyo Tanaka, and it is in her performance that the film becomes truly a masterpiece. It is a towering performance that is all encompassed within the film’s first few moments. With a jump from the current, elderly Oharu, to the spritely young Oharu, both played by Tanaka, the film not only introduces us to a character who has dramatically changed, but that plays on small, slight changes throughout this woman’s life.

From the very outset, hopes are high for the young Oharu. A former lady-in-waiting at a Kyoto imperial court, Oharu made one honest “mistake,” that of falling in love with a person below her own social and economic station, only to be uncovered and exiled for it. A startlingly bleak look at the strict social structure of Edo period Japan, and an even more bleak look at how even a choice as pure as choosing who one falls in love with can have dramatic negative effects on one’s life, The Life Of Oharu is a brazenly distilled picture from Mizoguchi.

In this distillation, Mizoguchi (and it has often been said that this was one of the auteur’s favorite pieces of work) fires on all cylinders, touching on themes and aesthetic beats that he would iron out throughout his career before and after. Often compared to a film like the also recently-released-by-Criterion-on-Blu-ray Sansho The Bailiff or his greatest film, Ugetsu in its meditations on freedom, class and the place of women in Japanese society, the film is actually most comparable to his last film, Street Of Shame. Both relatively episodically structured tales of women and their struggles within the rigid class system of Japan, Oharu feels like a not-so-distant relative of that later piece of work.

Featuring photography from Yoshimi Hirano, the film is one of the prettier motion pictures to come out of this period of Japanese cinema, something not all that rare when discussing works of Kenji Mizoguchi. From the opening tracking shots to the final frame of the film, the stark black and white photography and the equally contrast heavy use of lighting, the film holds within it much of the generational melodrama that Mizoguchi is best known for. It’s also deeply troubling and bleak as a drama can get.

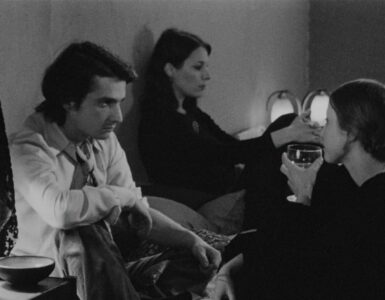

There is little hope found within these frames. Early on, the brightest scenes come with the burgeoning love of Oharu and the page whose love marks Oharu’s downfall, Katsunosuke, played by Toshiro Mifune. Their romance, while feeling a bit thin due to the film’s episodic structure, offers up the film’s few uplifting moments, even though it becomes clear as day that, if this love affair is discovered by outside parties, both involved will be ruined forever. Culminating in the death of Katsunosuke, following his proclamation that he hopes for a day where anyone is free to love anyone they feel affection for, an idea that is still relevant today, the film leaves this part of the story behind, only to find its lead character falling quickly down the social ladder. Getting bleak to the point where a man compares Oharu to a fish, able to be prepared and sold like they deem fit, the film is a brooding melodrama that takes the idea of one woman’s social downfall in Japan and spins a dark tale of a singular choice and its effect on one person’s life.

While the episodic structure does hinder the growth of a few relationships found within the film, The Life Of Oharu is simply one of the greatest films to come out of Japan’s cinematic golden age. Right at the height of Mizoguchi’s powers, the film would mark the beginning of possibly the greatest trio of films to come from one director, with Ugetsu and Sansho The Bailiff coming one and two years later respectively. It’s a dark tale of a woman’s downfall due to nothing more than falling for a person below her socially, and yet it’s also one of the most beautifully made films by one of cinema’s greatest poets.

And thankfully, Criterion’s Blu-ray is relatively stacked.

Dudley Andrew leads the way with a brief commentary on the film’s opening sequence, and it’s an insightful snippet into what should have really been a feature length master class on Mizoguchi’s masterwork. Andrew pops up again during an equally insightful audio essay entitled Mizoguchi’s Art And The Demimonde, and a documentary revolving around the travels of actress Kinuyo Tanaka in 1949 reveals just how big a name we watch in this film’s leading role. Toss in a great essay in the booklet from writer Gilberto Perez, and you have a release that may be missing a feature commentary or retrospective, but more than makes up for it in its new restoration and the breathtaking transfer. Deeply emotional and brimming with existential sorrow, The Life Of Oharu is a must own for any cinephile or any film fan looking to delve into Golden Age Japanese cinema.

![Bergman Island (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/bergman-island-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/this-is-not-a-burial-its-a-resurrection-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![Lars von Trier's Europe Trilogy (The Criterion Collection) [The Element of Crime/Epidemic/Europa] [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/lars-von-triers-europe-trilogy-the-criterion-collection-the-element-of-400x496.jpg)

![Imitation of Life (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/imitation-of-life-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (The Criterion Collection) [4K UHD]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/the-adventures-of-baron-munchausen-the-criterion-collection-4k-uhd-400x496.jpg)

![Cooley High [Criterion Collection] [Blu-ray] [1975]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/cooley-high-criterion-collection-blu-ray-1975-400x496.jpg)