One could be forgiven for taking Cecil B. DeMille’s production of Cleopatra as, on the face of it, a rather staid costume epic. I say that because that’s what I assumed it to be going in. And while DeMille doesn’t give up the allure of the epic, but rather emboldens it, he also undercuts it in some very key ways, making for a picture that feels very much of its place and time without cheapening the experience. It’s modernist in the best sort of fashion, led by a fiercely sexual Claudette Colbert in the title role and non other than smooth-talker Warren William as Julius Caesar. It takes us through all the highlights of Cleopatra’s biography, from her liaison with Caesar through his assassination and onto her doomed affair-for-the-ages with Marc Antony (Henry Wilcoxon).

As any adaptation of a subject such as Cleopatra must be, it’s as much a presentation of the legend as a story unto itself. When a seer tells Caesar to “beware the Ides of March,” it feels familiar to the point of intrusion, yet to exclude it would somehow do the film a disservice. Much of the rest of the dialogue, however, is strikingly naturalistic, fitting well within the seductive environment of the Pre-Code era in which is was made (just barely making the cut, in fact; it was produced a few months before the Hays Code was enforced). This conversational approach rankled critics at the time, who were eager for a more “high art” approach, but the difference between how the film was perceived then as compared to now might speak more about the times than the film. Casual films about the relations between men and women were littering the theaters, while today we’re overwhelmed by a distinct lack of naturalism in the cinema. It’s hard to imagine a studio today making a film of Cleopatra‘s scale without ensuring it emerge as blandly forgettable as Troy.

Also fitting well within the seductive environment of the time? Claudette Colbert, never more alluring. It’s easy to see why, at least in the context of the film, men let their kingdoms to ruin over her. Yet Colbert doesn’t rest merely on her natural appeal, bolstered though it may be by her many elaborately-revealing costumes. She finds an honesty to the character, a reason to keep watching after the robes go back on, so to speak. Colbert was one of those performers who was compulsively watchable, always active even when she was sedate, and she brings all her charm and personality to full force here. DeMille appropriately accords her close-ups in emotional moments and wide shots when she needs to play, assuring that all of her strengths will be brought to bear.

Naturally, it’s not all about the people with DeMille – the spectacle must have its day. It’d be easy, given the immense resources at his disposal, for him to merely rest on a series of wide shots, showing off his elaborate sets populated with a cast of dozens, but DeMille revels in them in a much more effective way, letting it be revealed to us slowly. He’ll pan back more and more and more on a set until we can scarcely believe any more will come, and choreograph his extras in a careful way, truly utilizing the artistic potential of the moving picture even as technology limited how much he could truly unleash. With most pictures of the early sound era, one is overcome by the sense of stasis, but guys like DeMille (or Lubitsch, or Sternberg) weren’t content with such excuses. They found a way to bring the cinema. Beyond the dramatics and well-wrought dialogue, Cleopatra is a very moving piece of cinema.

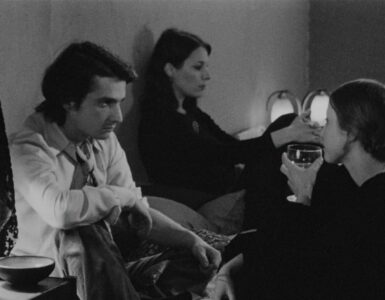

Re-emerging in a high-definition transfer from Masters of Cinema, I’d venture to say Cleopatra has never looked better. Full of deep, deep blacks (the MoC gang do like their deep blacks), and appropriately calibrated whites, the film really does seem to glow as only these old black-and-white films can. The grain keeps it looking nice and film-like. Though some may feel it too heavy, it seems about appropriate for a film from the early 30s. It does make the screencaps look a bit blurrier than is actually the case. In motion, this looks extraordinary – nice and crisp and exhibiting amazing depth (DeMille’s sets really go alllll the way back, and MoC does a great job of showing that aspect off). The film is presented in its original aspect ratio, 1.37:1. The screencaps have been resized and slightly compressed, but still communicate the basic virtues of the transfer. I have no complaints with the audio presentation, which has some of the hiss you’d expect from a film of its age, but is never obtrusive.

The special features are really wonderful, though you can probably stick to the disc, as F.X. Feeney’s commentary repeats much of the information found in the booklet, particularly the excerpt from The Autobiography of Cecil B. DeMille. Nevertheless, if you don’t mind some overlapping information, I highly recommend both. Feeney’s commentary is characteristic of him – thoroughly researched, but very energetic. Scholarly without ever being boring, he seems genuinely excited about the picture and director (never mind the star) about whom he has the pleasure of speaking, nicely mixing biographical and production information with insights into the film’s style and substance.

Next are three short featurettes, produced by Universal in 2009, and replicated from their DVD from that era (as was the commentary). One discusses DeMille’s legacy, both in his time and beyond, including some fun material that was shot as promotional material, perpetuating the legend of DeMille as something of a tyrant on set. The featurette on Colbert is much the same, discussing her rise in the talkie era and eventual stardom following It Happened One Night. Finally, a piece on the Pre-Code era is a nice summary of the time for those who aren’t familiar. On the whole, if you have a basic grasp on each subject, these won’t give you much more (though, again, the DeMille piece is a nice showcase for those promos), but as they each run 10-11 minutes, I doubt you’d really regret spending the time with them.

Finally, the booklet, which, in addition to the excerpt from DeMille’s autobiography, features a piece by Craig Keller titled “Describing Cleopatra,” which takes several screen shots and breaks down how they build up the film as a whole. It’s a bit sketch-like, however, sort of glancing over points that could have used more elaboration, and in some cases simply employing note-like formatting to convey points. The booklet’s a nice addition, but not on par with MoC’s usual output.

On the whole, however, Cleopatra is such a wonderful film, and the disc’s pleasures outweigh any concerns. They get it right where it counts. I, for one, was not terribly familiar with DeMille prior to seeing this film, but it’s such a singular, galvanizing force that I greatly look forward to finally diving into his work. On the strength of the film alone, the transfer, and Feeney’s commentary, this comes highly recommended.

![Bergman Island (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/bergman-island-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/this-is-not-a-burial-its-a-resurrection-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![Lars von Trier's Europe Trilogy (The Criterion Collection) [The Element of Crime/Epidemic/Europa] [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/lars-von-triers-europe-trilogy-the-criterion-collection-the-element-of-400x496.jpg)

![Imitation of Life (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/imitation-of-life-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (The Criterion Collection) [4K UHD]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/the-adventures-of-baron-munchausen-the-criterion-collection-4k-uhd-400x496.jpg)

![Cooley High [Criterion Collection] [Blu-ray] [1975]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/cooley-high-criterion-collection-blu-ray-1975-400x496.jpg)