In a shimmering black-and-white widescreen frame, a young girl reaches for the horizon, some spiritual force binding her to the soil.

It was recommended quite awhile before I finally had the chance to see Guillermin’s spellbinding 1965 feature that I go in knowing as little as possible, and I will, accordingly, do as little as possible to discuss the plot of the film here. The film doesn’t have any “twists” per se, and it doesn’t really do much of anything that isn’t perfectly in accordance with the type of film it establishes itself to be rather quickly. And yet there is a distinct pleasure to watch this psychologically warped fairy tale develop. There’s nothing overtly fantastic at play, and yet it feels otherworldly, teetering on the edge of mania without unraveling its tightly-wound core. The opening, pre-title sequence alone is uncommonly unexpected, jarring, and commanding, a quartet of repressed personalities on the verge of explosion.

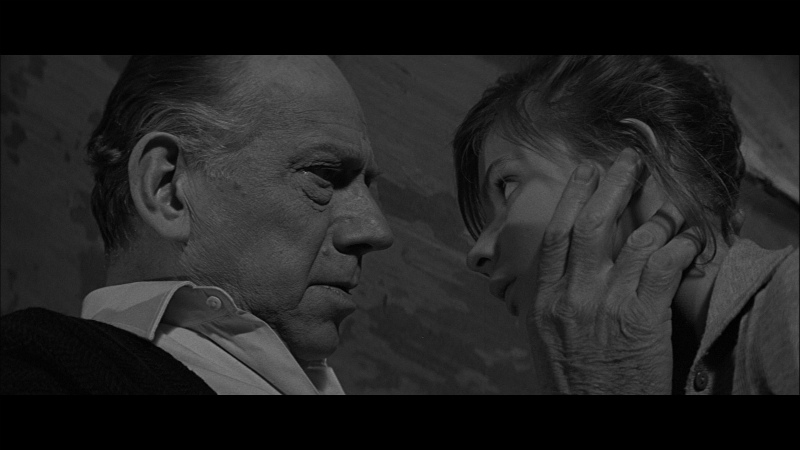

There is a girl, Agnes (Patricia Gozzi), clearly in the emotional and physical throes of adolescence, tightly attached to the girlhood that her father, Frederick (Melvyn Douglas), demands she leave behind without allowing her a moment of exploration. They have a housekeeper, Karen (Gunnel Lindblom), who does plenty of exploration on her own. Agnes lays in their garden, her arms outstretched, as though grasping for freedom. She tries to sleep, but her body will not allow it, demanding attention from her that she does not know how to give. At church, she clasps and wrangles with her hands during prayer. There’s an asylum near their house on the French seaside that her father walks her by after services, a gentle reminder of where he might throw her, should she completely lose control.

Tying a young woman’s burgeoning sexuality to insanity is not exactly unfamiliar territory for the cinema, even in 1965 (Repulsion was shown in the U.S. within months of Rapture; Marnie came out the year before). An entire book was written exploring the topic, which heated up in the late 1960s before exploding over the 70s and into the 80s. But in 1964, 20th Century Fox head Daryl F. Zanuck just wanted to make a movie like those steamy, daring European films that he – and much of the metropolitan moviegoing public – loved so much. He entered into a deal with French producer Christian Ferry, who brought on screenwriter Ennio Flaiano (who co-wrote ten films with Fellini, including La Dolce Vita and 8½), composer Georges Delerue (Hiroshima, mon amour and Jules and Jim), cinematographer Marcel Grignon (who had worked with Roger Vadim and Jacques Becker, no strangers to the erotic and the magic-realist), and, most importantly, director John Guillermin, a London-born Frenchman best known for franchise and blockbuster films (yes, kids, even in the 1960s!), whose attachment to his parents’ homeland left him hungry to make something a little more edgy, and a little more French.

He got it all with Rapture, and a collection of spectacular performers to bring it to life. We’re rather lucky when we get even one character in a film that feels like a fully-fleshed-out person, capable of surprising themselves, other characters, and us in the audience. Rapture has four. Gozzi in particular is a marvel, the central reason for the film’s success, and perhaps the best performance I’ve ever seen by someone under the age of 18 (she was fourteen during production, and would retire permanently from cinema a few years later), living purely not in the moment, but in the emotion of the moment. There’s never any doubt about what she’s feeling or thinking; the tension comes from why she thinks it, and where that may lead. She’s extraordinarily well-supported by Douglas, playing decidedly against his 1930s image of the suave bachelor. But it proves impossible to reduce him solely to the overbearing father; he has his own tangled backstory, his own passions, his own private contradictions, yearnings, weaknesses, and fears, many of which are alluded to more than directly addressed (the screenplay really stunning in this and many other respects). He takes tremendous joy in indulging the very daughter he’s also traumatizing.

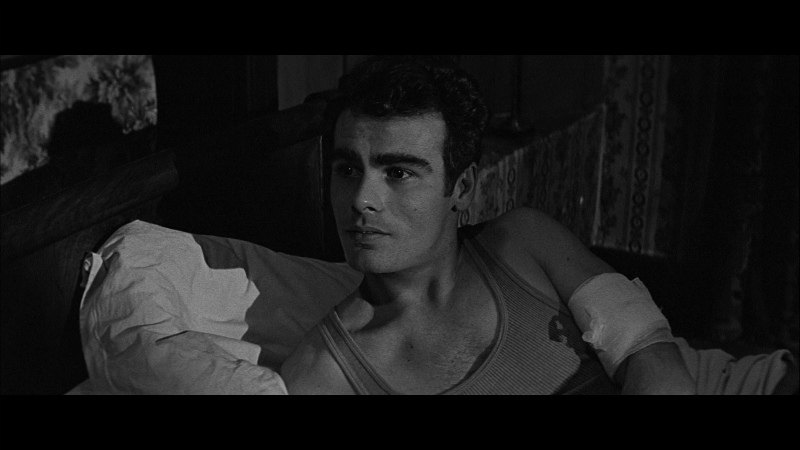

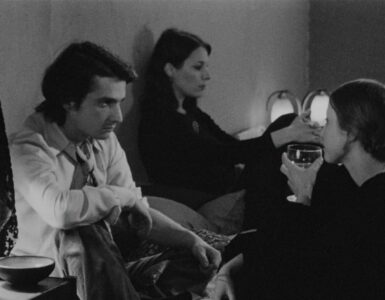

Even Lindblom, in a relatively straightforward role, turns surprisingly motherly towards the motherless Agnes, but not so much that she’s willing to put the child’s needs before her own. She has a very pragmatic sense of sexual attraction, but when one boyfriend visits her, she’s practically begging him for sex the moment he steps into her room. And then there’s Dean Stockwell, whose role in the story I will say especially little of. I tend to think women make the best film actors, and consequently, that the best male actors have something feminine about them, and so it is with Stockwell, whose expression is constantly curious, compassionate, and slightly wounded. He comes into this odd place under rather tough conditions, and quietly deduces those here are not too well off themselves. It’s not a pretty scene, and yet he stays anyway; partially out of necessity, but also because he understand the other three in distinct, fundamental ways that they deeply need, and which have gone otherwise sorely unfulfilled. Their interpersonal dynamics are just that – dynamic, constantly changing and revealing.

But while another director, in another time perhaps, would be content to let his characters do the talking, Guillermin seems incapable of shooting an uninteresting frame, either by virtue of composition, contrast in the editing, or simply catching the right face at the right time. It’s as accomplished visually as it is audacious, from a long tracking shot near the beginning the tours a rollicking party (full of silverware thieves and men’s roaming hands, which the camera captures quickly before abandoning for other acts of debauchery) to the way it swings about to put us firmly within Agnes’s confusion about her world and, indeed, very state of mind. It calls to mind Murnau’s American era and The Cranes Are Flying, and anticipates Kieślowski’s revelatory work in The Double Life of Veronique, all within a story that seems so much like a chamber piece that it could be been written by Ingmar Bergman.

This aesthetic wonder is spectacularly brought to life via Eureka Classics new (Region B locked) Blu-ray release. The grain structure is strong and varying, with only a few traces of damage remaining, totally crisp throughout (almost to a fault, in fact – there is a bit of edge enhancement in a few shots), and the whole thing seems to glisten, really putting the “silver” in “silver screen.” Contrast is superb, and depth is stunning, portraying some of the warping of the anamorphic process (which Guillermin and Grignon use to their compositional advantage, transforming limbs and bodies) quite well. Faces, landscapes, and rooms all have spectacular clarity and density. The screencaps here have been resized and compressed, but very well represent what you’re getting.

The disc has one major special feature, a commentary track by Nick Redmon and Julie Kirgo. Redmon and Kirgo run Twilight Time, which released the film on Blu-ray in the United States, and are more or less the ones responsible for whatever reputation it may gain from here (even if they admit that they only looked into the film at Guillermin’s personal urging, and had never seen it before). That said, this is not a very well-prepared track, often falling into just narrating the events onscreen. There is not a lot that’s been written about the film, though, so for those who fall for it as much as I did, it’s still a very valuable listen to gather what little is known, just go with the flow during their rather tepid analysis. Eureka also includes a booklet with an essay by Mike Sutton, which goes over some of the same information as the commentary, focusing much more on production than analysis.

I absolutely adored this film, this strange little creation, an anomaly in the careers of nearly everyone involved, left to the side of film history by some strange combination of circumstance and its difficulty in categorizing. Its influences are myriad, intertwined and yet just distinct enough to result in a film that doesn’t quite fit anywhere, but which is so urgently and passionately told, and now so readily available, that ignoring it any longer is simply impossible. It commanded my attention from its earliest moments, and has lingered defiantly in my mind over the past week, burrowing deeper, revealing its complexity bit by bit. I look forward to it continuing to do so. This gorgeous Blu-ray comes with my highest recommendation. Revel in it.

![Bergman Island (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/bergman-island-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/this-is-not-a-burial-its-a-resurrection-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![Lars von Trier's Europe Trilogy (The Criterion Collection) [The Element of Crime/Epidemic/Europa] [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/lars-von-triers-europe-trilogy-the-criterion-collection-the-element-of-400x496.jpg)

![Imitation of Life (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/imitation-of-life-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (The Criterion Collection) [4K UHD]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/the-adventures-of-baron-munchausen-the-criterion-collection-4k-uhd-400x496.jpg)

![Cooley High [Criterion Collection] [Blu-ray] [1975]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/cooley-high-criterion-collection-blu-ray-1975-400x496.jpg)

Enjoyed this review. I should perhaps point out that I wrote the essay before I had heard the commentary so I didn’t know what they were going to talk about.