I don’t know what things are like where you are, friend, but here in Los Angeles, there’s a very strong, almost insistent, cinematic culture surrounding “cult” “classics” from the 1980s. The weirder, the better. I mostly avoid this scene, as it routinely becomes a gathering of the Too Smart For It Society, the members of which are determined to openly mock anything that unspools before them. The weirder, the more laughable; the more laughable, the “better.” I’ve never understood this approach to cinema, but, as the object of mockery typically is not a type of film in which I have a whole lot of interest, never felt it a great loss. As long as they stay away from the pre-1970s rep screenings around town, we’ll all coexist together, but separate.

Now, after seeing Night of the Comet, I fear I’ve been avoiding an entire avenue of potential genius.

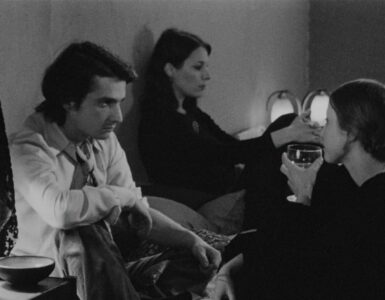

The conceit of writer/director Tom Eberhardt’s 1984 feature is deliciously simple – what would teenagers do at the end of the world? Eberhardt furnished the early drafts of his screenplay with precisely that question, asking youths of the day how they’d react, and incorporating their responses into the finished film. The teens in question are Reggie (Catherine Mary Stewart) and her sister Sam (Kelli Maroney), who, after spending One Fateful Night in separate metal shelters, are protected from the rays of a passing comet that incinerates or zombifies the Earth’s population; at least, that of the Los Angeles area.

Eberhardt was reportedly aghast at the lack of perspective and humility the teens he interviewed had at the prospect of the world ending (still a hot-button issue in the later years of the Cold War), but it is precisely that narcissism that makes Night of the Comet such an exceptional picture. Well, that and zombies and machine guns and secret organizations. But none of that would be nearly as interesting if not filtered through the lens of Reggie and Sam’s utter obliviousness. Sam has it worse. As would be the case for most of us, she hardly believes her sister’s claims at first, and even when presented with mounting evidence that nearly everyone she ever knew is dead, she fiercely maintains a sort of positivity, hoping that everyone will just come out from around the corner. After all, if the whole world revolves around her, how can so much go so wrong when she’s there? Maroney does exceptional work, finding a real honesty in that demented sense of optimism (even filtered through self-absorption), constantly throwing a mischievous arch of the eyebrow our way, letting us know she always has something up her sleeve.

Stewart doesn’t make for as fine a lead, but there’s something about her lack of affect or training that endears her nonetheless. There’s a scene late in the film in which she’s being interviewed about her medical history, and the rather cold doctor asks if she’s ever been pregnant. She mentions a time when she thought she was once, which he assures her is not all that important. “That’s what you think,” she replies. “It was the longest three weeks of my life.” Her lack of conviction is what sells it, a guard she puts up to deflect both her nervousness about the situation she’s in, and recalling such intimate details in front of a stranger. It doesn’t work in every scene, but it’s an interesting layer regardless.

Like many films by Howard Hawks, Jean-Luc Godard, or Quentin Tarantino, Night of the Comet is in some ways the B-movie programmer it purports to be, but it’s also a genre film about people who have seen genre films. Or maybe even know they’re in one themselves. There’s a sense of play afoot, not just in more obvious sections, as when the girls go shopping in a now-abandoned mall. The way they, and the film, approaches the zombie/mutant creatures, or the secret organization, takes for granted that we have seen these sort of tropes before, and toys with their presentation. Reggie and Sam are reacting as much to their pop culture past as to the actual threats in front of them.

All of which makes the film a blast to watch. It has a real upbeat spirit to it, its own rhythm, recognizing the unfair nature of life (there’s a really wonderful scene between Reggie and Sam in which the latter realizes all she’s lost) without overly dwelling on it. It’s a film that uses its genre to acknowledge suffering, but to choose community, togetherness, and optimism. A welcome reprieve from the bulk of genre cinema.

Arrow Films has put together an incredible package for Night of the Comet, starting with an excellent, filmic high-definition transfer. It’s not nearly as artificially boosted as some of Arrow’s other efforts, and while the results are sometimes less eye-catching, they also feel much more honest to the source. Colors are especially fine, as the sky is frequented blanketed in an orange glow after the comet’s had its way with us, lending an eerily hot tone to some of the early scenes. Stability, contrast, and clarity are all very well-rendered.

But the real show is in the supplements. First up, we get three whole unique commentary tracks. The first features Stewart and Maroney, who share memories of how they got involved in the film, what the set was like, and its continued effect on both their lives. Maroney’s recollection is especially strong, and she seems to have a real passion for the movies in general. Eberhardt provides a commentary track as well that’s obviously more focused on what he intended to do with the film, thematically and emotionally, as well as discussing the (sometimes charming) production challenges of low-budget filmmaking. The final one is with production designer John Muto, whose contributions go a long way to sell the reality of the world.

From there, we get a series of interviews with other members of the cast and crew. “Valley Girls at the End of the World” features Stewart and Maroney again, and mostly rehashes information from their commentary. “The Last Man on Earth?” features actor Robert Beltran, who plays another survivor the girls meet and team up with, who speaks very candidly about his hesitation in taking the role, eventually recognizing the rarity of a Mexican-American getting such a character (and a little matter of top billing goes a long way, too). “End of the World Blues” features Mary Woronov, who plays one of the scientists at the spooky organization, who is even more candid than Beltran in addressing the way a project like Night of the Comet is perceived at the time of its making, only to turn into something people remember and talk about thirty years later. Finally, in “Curse of the Comet,” makeup supervisor David B. Miller talks about how Night of the Comet was the first film he got to be in charge of, and the huge difference it made in his career after a few years of assisting Rick Baker. Film critic James Oliver provides the essay in the included (and quite attractive) booklet, nicely outlining the film’s major themes and appeal.

I was somewhat dreading this film as it neared the top of my stack of review discs, but I couldn’t have been more surprised by it, nor more delighted to dwell on it as I watched the supplements in the days to come. What seems at first like a goofy programmer is an immensely endearing, surprisingly thoughtful examination on what really matters in life, and the persistence to move forward. Arrow’s new Blu-ray edition more than does the film justice.

![Bergman Island (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/bergman-island-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/this-is-not-a-burial-its-a-resurrection-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![Lars von Trier's Europe Trilogy (The Criterion Collection) [The Element of Crime/Epidemic/Europa] [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/lars-von-triers-europe-trilogy-the-criterion-collection-the-element-of-400x496.jpg)

![Imitation of Life (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/imitation-of-life-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (The Criterion Collection) [4K UHD]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/the-adventures-of-baron-munchausen-the-criterion-collection-4k-uhd-400x496.jpg)

![Cooley High [Criterion Collection] [Blu-ray] [1975]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/cooley-high-criterion-collection-blu-ray-1975-400x496.jpg)