At this late stage of its development as a sub-genre of modern cinema, the “Holocaust movie” has become an increasingly dicey endeavor for both filmmakers and their audience. For roughly the past fifty years or so, stories set in a context of the Third Reich’s ascendancy have been a reliable go-to subject for writers pondering dark and disturbing themes that bring to the surface the more troubling tendencies of human nature. Not just the cruelty of the perpetrators of the genocide, but also the cynical indifference of “respectable citizen” bystanders and the crazed desperation of prisoners who make anguished decisions that keep themselves alive at the cost of inflicting suffering on someone else – as well as the valor of those who sacrifice their own self-interest in order to protect the innocent and vulnerable among them.

There’s little debate that some of the most memorable and emotionally impacting films of the past half-century have drawn (often reluctant) attention to this damnable chapter of our history. The hope was that lessons learned from its contemplation will prevent such atrocities from ever happening again, or at least keep us on alert to ensure that they’re brought to the light more quickly than they were in the late 1930’s, when Hitler’s minions carried out the Nazis’ murderous ambitions and the world looked the other way. A few that stand out to me include mainstream Oscar winners like Schindler’s List, The Pianist and Sophie’s Choice to foreign offerings embraced by the Criterion Collection such as Au revoir les enfants, Kapo, Army of Shadows and a film that I recently reviewed on my Criterion Reflections blog, The Shop on Main Street. Of course, we also have numerous powerful documentaries, including Night and Fog and Shoah (which I still have not seen yet – still looking for the right occasion to stare into the abyss with that one…)

Sadly, we’ve come to learn that for all of cinema’s power to shape our understanding and perception of the world, hatred continues to express itself in massively destructive and violent ways, in conflicts that even as I write are boiling over in numerous flash points of carnage all over the world. I’m not so naive as to assume that these tragedies could have been prevented if only those who command and those who carry them out had “seen the right movies.” But even from an artistic and critical perspective, an argument can be made that the vitality of the Holocaust film has descended to the point where it’s difficult to create a new angle on the story that hasn’t already been reduced to cliche. In most cases, the depravity of the concentration camp is nearing its terminus as a subject capable of yielding worthwhile fruit. At the very least, it’s a subject best left out of the hands of those who can’t resist the temptation of reaching beyond their grasp to make grandiose statements that too often reek of emotional manipulation or rote denunciations of a common villain that most audiences can easily agree to hate without touching on more contentious and contemporary political nerves.

But there was a time when such territory was still fresh, provocative and largely unexplored in the movies. Such was the case in 1965, the year that director Sidney Lumet and lead actor Rod Steiger teamed up to give us The Pawnbroker. That was the same year that The Shop on Main Street emerged from the then-exotic cinema culture of Czechoslovakia to amaze audiences en route to winning its “Best Foreign Picture” award from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Though I’m reasonably certain that the two films were produced in complete isolation from each other, their thematic similarities and the close proximity of their release dates made for some fascinating comparative viewing over the past week. And I’m quite pleased to report that, despite the flood of films dealing with such material that have been produced over the past five decades, The Pawnbroker still packs a very powerful punch, thanks mainly to Lumet’s and Steiger’s brilliance, but also greatly aided by solid collaborations in other aspects of the film’s creation.

The titular subject of the story is Sol Nazerman, a former university professor and concentration camp survivor whose memories of a midsummer’s idyll spent with his family provide the film’s opening scenes. In a sun-washed, slow motion prologue, we meet his wife, his children and older relatives, frolicking in an open meadow, before they are rudely interrupted by a menacing presence. We’re not told exactly what happened right away, but it’s obviously a flashback to a happier time, now some twenty years distant in the past. We cut to Nazerman lounging restlessly in a large open backyard space that he shares with a cluster of neighboring homes in a Long Island housing development. It’s a great shot that manages to capture both the indolent affluence and vapid banality at the tail-end of that first wave of American suburbia in the early 1960s that gave birth to the Baby Boom generation. But we spend little time in that environment, as it’s really just the token of “achievement” that Nazerman can point to if he’s ever called to account for what he’s made of himself since his old life fell apart back in Europe.

Instead, Nazerman spends the bulk of his time, and exerts what little life force still remains within the husk of his persona, in slummy environments: his soulless high-rise apartment in the Bronx where he lives (the Long Island subdivision home that he helps pay for belongs to his late wife’s sister) and the grimy pawn shop that he operates in Harlem. Far from being driven into such seedy environments due to lack of opportunity, it seems as if Nazerman has made an intentional decision to dwell in a cavernous, impersonal outpost of modernity and do business with the dregs of his adopted society to prove some kind of a point – perhaps a justification of the extreme apathy and disgust that he feels toward his fellow humans.

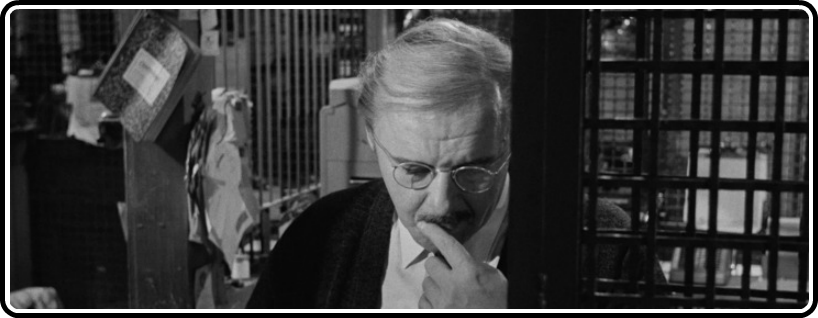

As anyone who’s ever been compelled to do business in a pawn shop knows all too well, it’s a particularly sordid form of transaction that occurs in such establishments. The establishing scenes that illustrate Nazerman’s daily routine are like a method acting workshop, giving a steady rotation of bit players their chance to chew the scenery for a few minutes as they approach Nazerman’s caged countertop with detritus from their lives that they seek to turn into quick cash for various and sundry reasons. Sol’s manner with each of them is brusque, heartless, indifferent – he quietly preys on their poverty with a blank “take it or leave it” coldness that invariably deflates their hopes and leaves them little choice but to succumb to his meager offer. Of course, most of what they’re pawning is cluttery junk that’s destined to sit on his shelves long after the redemption ticket has expired, but there’s no doubt that Nazerman is coming out ahead on every negotiation. It’s just how he operates – and his advantage is cemented in any case, as we learn that he’s also operating a money-laundering front for Rodriguez, a local crime boss. That’s where the real action is, where the money that keeps his in-laws afloat originates. More virtuous viewers may regard Nazerman as having made a bargain with the devil to achieve and maintain his prosperity, but compared to the demonic powers he left behind in the old country, Rodriguez and the two-bit hoodlums who hover around his shop are small-timers that The Pawnbroker shrugs off with hardly a second thought. All that really matters to him at this point is money:

But in spite of his contemptuous, authoritative assessment of the people around him and the meaning of life, Nazerman’s cold-hearted disdain functions as an emotional armor that he uses to block out painful recollections of traumas that he endured, and that killed the wife and children he loved. Through extremely short (one second or less) flashback cuts, visualizations of long-suppressed memories, we see the cracks emerging in that protective shield as it buckles under the mounting pressures of adversarial run-ins with his sad-sack customers, brawling neighborhood crooks and the prying gaze of a concerned social worker who intuitively recognizes the suffering that Sol is barely able to manage. Nazerman’s gradual breakdown is captured so evocatively, thanks to the inspired combination of Lumet’s incisive direction, Steiger’s masterful command of an intense emotional palette, top notch cinematography by Boris Kaufman (Oscar winner for On the Waterfront) and the brilliant editing of Ralph Rosenblum, who went on to do some great work with Woody Allen in the mid-1970s.

In addition to the engrossing story that keeps first time viewers guessing as to how it will all turn out (though the cover art functions as a significant giveaway), The Pawnbroker features a vibrant, jazzy soundtrack by Quincy Jones (his first major film assignment in that capacity) and several extended scenes of vintage New York City streetscapes, an environment that Lumet spent a lot of time filming over the course of his distinguished career. This movie even played an important role in the final dismantling of the Motion Picture Production (Hays) Code, as the first Hollywood film granted an exception from the guidelines to show naked female breasts (the exposure of which was integral to a key scene, hardly for erotic arousal – indeed, quite the opposite effect was intended and achieved.) All in all, The Pawnbroker has all the credentials necessary to justify its release as a Criterion title, but instead, the Blu-ray release comes to us courtesy of Olive Films, with the upside of reducing the retail price substantially, along with an impeccably crisp transfer and solid technical specs. The downside is, that’s all we get – a great film, nicely delivered on physical media, but no extras whatsoever. No booklet, no trailer, no making-of featurettes or any other background info save what you get on the back cover. As much as I enjoy those extra touches that Criterion routinely provides, the truth remains that a lot of that information can be gleaned in a short amount of time spent searching the web – so if we’re able to save a few bucks as we fill in the gaps on overlooked phases of a great auteur’s filmography, and get more of these neglected works out on disc that are unlikely to come to a streaming service near you anytime soon, then I’m glad we have a company like Olive Films out there filling this niche.

![Bergman Island (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/bergman-island-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/this-is-not-a-burial-its-a-resurrection-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![Lars von Trier's Europe Trilogy (The Criterion Collection) [The Element of Crime/Epidemic/Europa] [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/lars-von-triers-europe-trilogy-the-criterion-collection-the-element-of-400x496.jpg)

![Imitation of Life (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/imitation-of-life-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (The Criterion Collection) [4K UHD]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/the-adventures-of-baron-munchausen-the-criterion-collection-4k-uhd-400x496.jpg)

![Cooley High [Criterion Collection] [Blu-ray] [1975]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/cooley-high-criterion-collection-blu-ray-1975-400x496.jpg)