“Nobody can play comedy who does not have a circus going on in his head.” – Ernst Lubitsch

Perhaps because the transition had such a titanic impact on production and distribution, it becomes tempting – easy, even – to view a filmmaker’s silent work as somehow apart from their latter entries. This becomes doubly touchy if the director is believed to somehow favor particular aspects that one mode or the other specializes in. For this reason, I’ll admit, I was pretty hesitant for awhile to take a look at the silent work of Ernst Lubitsch, given his talkie fascination with sparkling dialogue full of double entendre, but the more I watched his sound films, the less that stood out to me as his defining attribute; the dialogue is lovely, but ultimately meaningless without his method of choreography, moving the actors together and apart in distinct rhythms, timed to the dialogue certainly, but not beholden to it. Criterion’s Eclipse set of Lubitsch musicals became particularly informative, revealing the melodic quality in all of his films, the way actors sing every line and dance every step – perhaps the famous Lubitsch touch was, in part, a way of making musicals out of everything.

So, if one can imagine a silent musical (and what with the pantomime and such, the silent film is already a close cousin of dance), that’s largely what Masters of Cinema’s Lubitsch in Berlin set offers, and once I accepted that the range of Lubitsch’s artistry stretches well beyond the spoken word, I found that these six films fit in very well with his more famous talkies. And why not start with the best of them – 1919’s The Oyster Princess, a sort of political cartoon wrought even larger. It tells the story of an American oyster magnate, his daughter, and her sudden husband-to-be, a destitute prince. There’s a way in which their vast mansion (at one point, a character is handed a blueprint that, from afar, looks to be a geographic map of a small nation) operates as a sort of factory, with their hundreds of employees each being assigned to very small facets of very small tasks, often doubling up therein. And if you want to let things rest with the sort of facile political reading, there you have it.

But, to quote the Oyster King’s refrain, “That does not impress me at all.” What does impress me, what kept me practically laughing for the entire hour of its duration, not merely at its many jokes, but at the sheer ingenuity of it all, is the constant dance, the unfolding, ever-expanding nature of the mansion, the way a door will open to reveal two dozen maids ready to carry their mistress to her bath, how each person moves carefully within Lubitsch’s rhythm that he so tangibly creates without the benefit of overseeing any soundtrack. Woe is the poor piano accompanist who has to follow the beat, which at once an ever-mounting orgiastic explosion, yet constantly changing, diverting, and dodging. The orchestral score that is included with the Masters of Cinema edition is truly exceptional, and goes beyond merely supporting the film to directly informing its jaw-dropping power.

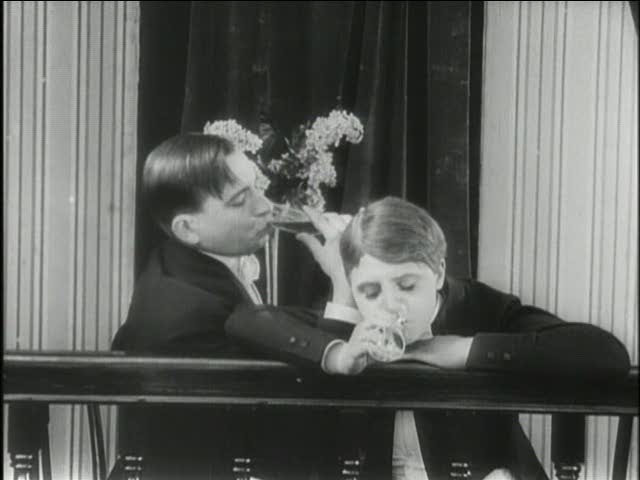

Every character is some exaggerated, horrific version of itself. The Oyster King, Mr. Quaker (Victor Janson), is not merely a fat cat, constantly trying to keep himself as comfortable as possible – the whole house seems to bend to his whim – a series of butlers carefully arrange him on a couch for an afternoon nap; he keeps four newspapers on hand since he seems to expect his daughter to destroy the first three; there are buttons installed that will instantly summon a dozen servants; an entire wedding celebration is assembled in a matter of hours. His daughter, Ossi (the transcendently talented Ossi Oswalda), isn’t just a spoiled brat – whole rooms seem to exist purely for her to smash when she gets into a rage; she keeps a suitor waiting while dozens of maids bathe and dress her; she is truly a princess in every sense. Her eventual prince is not merely poor, in the sense that he has nagging creditors or fewer possessions – he lives in absolute poverty, to the point that, when guests arrive, he and his right-hand man simply throw their belongings to each side the room and prop a chair up on a box to craft some kind of throne. The Oyster Castle (as I call it) is the very definition of ostentatious. The food seems endless. The sudden explosion of the foxtrot goes on forever, their band leader dancing about. The band itself includes one man simply sawing a piece of wood, and another who slaps the face of a third to the beat. This movie includes dozens of women participating in a melee foxy boxing tournament.

And I know this is, in part, to be taken as a damning statement of American excess, but I just cannot help but marvel at the specific way in which Lubitsch has rendered this excess. The film is billed in its opening credits as a “grotesque comedy,” and it is most certainly that in every sense of the word. But what exaggeration, what distortion…what a beautifully absurd orgy. Lubitsch can get the most out of a close-up (Janson’s face is a particularly good subject), but generally keeps as wide a shot as possible to take in all the madness and give performers like Oswalda plenty of room to wreak havoc.

Oswalda, it turns out, was a pretty key collaborator for Lubitsch in these early, wild days, and really brings out a different kind of energy than we’d see from the actresses in his sound films (though Miriam Hopkins particularly manic moments feel like a natural, talkie extension of this, and in either case, the assertion I once heard (I believe on the commentary track for the Criterion release of Trouble in Paradise) that Lubitsch held a personal preference for chatterbox blondes over smooth brunettes certainly rings true). She gets front-and-center treatment in I Don’t Want to Be a Man (translated more directly, and clearly, as I Wouldn’t Like to Be a Man), in which she plays a tomboy who, upon tiring of the rather limited possibilities of being a woman in those grand old days, decides to assume the identity of a young man and have a grand old time, only to find her imagined paradise to be quite less dazzling than all that.

As fun as it is to watch Oswalda tear everything to hell early on in the film, she brings a very refined touch to her time “as a man,” wherein Ossi (all her characters in these films are called “Ossi”) suddenly feels intensely at home. As a woman, she seemed barely in control of her limbs; as a man, she is cool, calm, and just a little bit more merry than those around her. To watch her strolling down the street without a care in the world, slurping down liquor with the best of them, and even testing her skills with the ladies is all quite a wonder. She was in her late teens during this period, and really exemplifies that quality that makes some young people so magnetic onscreen – you really feel, as she might have, that she has the world by the tail, and is capable of anything. Perhaps that’s why I Don’t Want to Be a Man feels so well-suited to her, as her character is making a similar discovery.

The Doll, another feature role for her, takes a second to set up, but bear with me – a young heir, tired of his family’s nagging insistence that he marry, asks a manufacturer of lifelike dolls if he may buy one to hold a fake ceremony. The toymaker ends up recommending a doll based on his own daughter, but before the doll is brought to show, his apprentice breaks it. The daughter, not wanting the apprentice to be punished, poses as the doll, a ruse she feels forced to maintain even after the groom-to-be decides to buy her. This gives Oswalda plenty to play with physically, at once trying to bend to her owner’s every whim, yet maintain some semblance of interior dignity amidst all the poking and prodding, never mind the moments she has to herself, when we’re reminded that she still has to, you know, eat from time to time.

The film begins with Lubitsch himself setting up a model version of the set of the opening scene, as informative a scene for his entire career as one could possibly ask for, and one he happily exploits in this picture in particular. Blatantly unreal sets normalize the blatantly unreal land, in which something like The Doll – which is neither robot nor toy, yet somehow both – could even exist, in addition to the rather fantastical flourishes Lubitsch grants it. The only great downside to the film’s inclusion in this set is that it features an extraordinarily poor score that doesn’t jive with its tempo or mood in the slightest.

As much as the artificiality of The Doll helps us better understand I Don’t Want to Be a Man and especially The Oyster Princess, this becomes central to looking at Sumurun (alternately titled One Arabian Night) and The Wildcat, which both employ one of the more outlandish tricks I’ve seen in cinema, which in turn directly connect Lubitsch’s work here to the German Expressionism movement going on at the time – cut-out facades that change the shape of the frame. Sometimes these will accentuate the set or call our attention to a particular element of the frame, but especially in The Wildcat, Lubitsch just starts using them simply because they feel right. This attribute aside (and the rather placid Anna Boleyn also employs them a couple times), Sumurun and The Wildcat could scarcely be more different; the former is a rather complex series of romances and heartbreaks, cut with some rather audacious comedy bits involving a corpse, and a Keystone-Cops-esque chase scene involving a bunch of girls from the sheik’s harem and their eunuch guards; the latter is a military screwball comedy of sorts, in which a lieutenant falls for a bandit girl living in the wilderness.

The Wildcat proves to be a foundational film for Lubitsch in two respects. First, the lieutenant character is nearly identical to the one Maurice Chevalier would play for the filmmaker in works like The Smiling Lieutenant and The Merry Widow; he’s outlandish, womanizing, gleefully amoral and seems to take every step with a song in his heart, and yet, in spite of his selfish nature, he is beloved. As he departs the town in which he lives for an assignment at an outlying post, hundreds of women flock to the streets to praise him, and about three dozen young children wave “goodbye, Daddy!” (a scene that exemplifies Lubitsch’s more-is-more philosophy as well as anything in The Oyster Princess). Like much of Lubitsch, it’s as funny as it is cutting, and only one because it is the other.

Additionally, the film ends with the bandit woman (played by Pola Negri, another key early collaborator for Lubitsch) realizing that, despite their feelings for one another, her manner of living is grossly incompatible with the lieutenant’s, and she sets about demolishing his affections by accentuating this gap. Lubitsch is fascinated with men and women who would be perfect together if not for the fact of their station in life and upbringing, one of those themes that was quite potent in the first half of the twentieth century, when people of varying factions would actually come to associate with one another, but which in the second half has become increasing quaint, to the point that today it is hardly thought of at all (mocked outright, in fact, in a recent episode of Glee). But this longing is crucial to the finales of The Smiling Lieutenant, Trouble in Paradise, One Hour With You, and Angel, never mind the entire emotional fabric of Design for Living. When some refer to Lubitsch as a rather detached filmmaker, unconcerned with the emotional fabric of romance, I wonder if they have any conception with just how pervasive notions of class and status were in society at the time, and, while it’s all well and good to critique, mock, and exploit such issues for screwball comedy, at the end of the day, we’re still left to contend with them in very real ways.

It is perhaps for this reason, Lubitsch’s reflexive ability to infuse his comedies with such poignant drama, that his outright dramatic features are often problematic. It is not accidental that the elements of Sumurn I immediately called attention to were its more outwardly comedic, though at least the drama there is more invested than in Anna Boleyn, as dull a piece of historical drama as has ever been wrought onscreen, a film entirely content to let its importance do the talking. Sumurun, on the other hand, perhaps set free by its “exotic” setting (the then-very-much-in-vogue “Orient”) and complex series of plot developments (involving a sensual dancer, a sheik, a clown, a cloth merchant, a Prince, and the aforementioned harem and eunuchs). That the film is even titled after but one of these characters is a little odd, given that she’s granted little, if any, more importance than any of the others, and that two other characters so obviously steal the show – Pola Negri as the dancer and Lubitsch himself as the clown, whose affections the dancer ignores.

Lubitsch is rarely thought of as an actor-turned-director, and yet, he began in a performative role, one he continued into the first few years of his career behind the camera, and aside from the brief cameo at the beginning of The Doll, this is the only opportunity you have to see him perform in this set. While not what I would call a great actor (in an interview with Peter Bogdanovich on Criterion’s release of Trouble in Paradise, he relates a story Jack Benny told him about how Lubitsch would perform many of the roles for the actors to give them a sense of what he wanted; Benny noted that these performances were usually “a little broad, but you got the idea,” a description that probably serves as an understatement coming from a guy like Benny), and definitely one suited to the silent era (in the documentary accompanying this release, it is suggested that, had he not moved behind the camera, Lubitsch would have been relegated to, at best, a distant footnote in cinematic history), Lubitsch is perfectly suited to the caricature that a role like “the tragic clown” would require. His way of overplaying adoration for the dancer becomes a sort of desperate mask, at once completely admitting his feelings and yet conveying a certain knowingness, in a jovial way, that she is way out of his league. Plus, given that the film requires him to play the role of a supposed corpse for a great length of his screen time, it’s abundantly evident that he was willing to sacrifice himself to whatever the work required, and must have been something to see onstage, where he began.

To drastically understate another point, however, there is really no secret why Negri became such a success overseas. The sexuality of a young woman (she was 22 or 23 when this was made) has long proven to be one of those things that is not limited to any culture or language, and the role she works with here in certainly ripe for everyone to exploit. The dancer has tremendous confidence when performing, all too used to the effect she has on men, and her ability to capitalize upon it, but it’s the way she contrasts that with uncertainty about her personal life that really elevates it, especially how to handle the affections of Lubitsch’s clown, that gives the role (and film) its more modern edge, relating that impossible dilemma of discouraging the feelings of someone in whom you have no romantic interest without completely alienating him, if such a feat is even possible (oh, the demands men make of women). It’s one thing to know how easy it is to seduce men for their money; quite another to figure out what to do with them afterwards.

This is a rerelease of a set originally put out in 2010, and the DVD-only transfers look fine enough for being created at that time with materials from foreign films made that long ago. Damage is actually surprisingly minimal, and contrast is handled nicely across all tinting styles. The Oyster Princess is in the worst shape, unfortunately, missing quite a few frames, which upsets a bit of the rhythm of the comedy (luckily, masterpieces can withstand a few hits, and the jumps are never so great that I was unable to account for the goings-on in between). When faced with those cut-out frames, the black area is not reduced entirely to black, but rather is presented as a filmed object as well, with its own set of flaws and dimensions. The real gem is just having these available, but MoC have done fine work in going the extra mile. (Note: The screenshots here were culled from a variety of sources, and should not be taken as necessarily representative of the quality of the transfers).

The only real supplement is an 108-minute documentary appropriately titled Lubitsch in Berlin, which takes a look at that period in the filmmaker’s career, featuring interviews with many German and American scholars and filmmakers (including Lubitsch’s daughter, Nicola, and director Tom Tykwer). It’s an incredibly valuable asset for fans of Lubitsch, the overview of whose career is too often relegated only to his Hollywood sound films, and this documentary proves illuminating not only to his earlier years, but, in reflection, for his sound work as well. Definitely one to wait to watch until you’ve seen all the films in this set, and as many others as you can must, but well worth it once you do.

MoC also provides a booklet, with very short blurbs on each film by Anna Thorgate, Ignatiy Vishnevetsky, and David Cairns. They’re helpful, but the very definition of “bonus material” – stuff that’s a nice addition to something you’ll want to own otherwise, but which largely won’t affect your purchase.

3000 words later, you can imagine this set gets nothing but the highest recommendation from me. Lubitsch is one of the greatest filmmakers who ever lived, and a personal favorite of mine. Those new to him entirely might want to start with Trouble in Paradise, To Be or Not to Be, One Hour With You, or The Merry Widow, but these films – in particular I Don’t Want to Be a Man, The Doll, and most especially The Oyster Princess – should also warrant immediate consideration, especially for those already inclined towards silent cinema. As much as I thought I had Lubitsch pretty well figured out, these were astounding, eye-opening experiences, breathlessly entertaining and boundlessly inventive.

![Bergman Island (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/bergman-island-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/this-is-not-a-burial-its-a-resurrection-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![Lars von Trier's Europe Trilogy (The Criterion Collection) [The Element of Crime/Epidemic/Europa] [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/lars-von-triers-europe-trilogy-the-criterion-collection-the-element-of-400x496.jpg)

![Imitation of Life (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/imitation-of-life-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (The Criterion Collection) [4K UHD]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/the-adventures-of-baron-munchausen-the-criterion-collection-4k-uhd-400x496.jpg)

![Cooley High [Criterion Collection] [Blu-ray] [1975]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/cooley-high-criterion-collection-blu-ray-1975-400x496.jpg)