Cinema is an interesting narrative entity. Something inherently visual, film has primarily been fodder for either entirely experimental anti-narratives or pieces of fiction that are so bogged down by plot that they become both cumbersome and lifeless. Only in the middle ground, these aesthetically daring but narratively taut pictures do we find truly great pieces of drama, comedy, action or any combination of these.

And then there is David Lowery’s new feature film, Ain’t Them Bodies Saints. While he does have a series of shorts and a couple of features under his belt as a director, he’s likely better known to the masses as an editor, including work on Shane Carruth’s masterpiece from earlier this year, Upstream Color. Now, while that film may in fact be a perfect jumping off point with regards to this picture, as would be the work of director Terrence Malick, an influence all but proclaimed at the top of this film’s lungs, this is something unlike anything either director has crafted, for better and for worse.

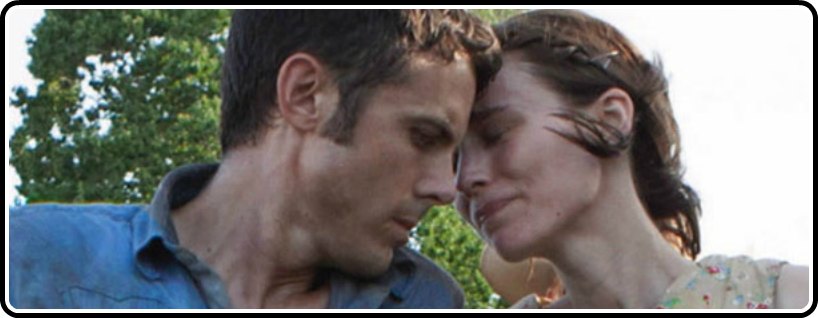

To the naked eye, Lowery’s picture is not much more than an ant-Western through the lens of a lyrical filmmaker like the aforementioned Malick. Much of the actual narrative is told through sequences the viewer comes to late or in half spoken monologues, best seen in the film’s opening few moments. We are introduced to a couple, Ruth Guthrie and Bob Muldoon (played by a rarely better duo of Rooney Mara and Casey Affleck) who are broken apart after a heist goes wrong. With Bob in prison, Ruth must raise their new daughter all by herself, only to hear that Bob, years after getting into prison, has escaped. With Bob hell bent on reuniting with his family, Ain’t Them Bodies Saints has ostensibly a rather standard premise, that seems like an ultimately unremarkable setup for a modern day neo-Western.

However, with themes of loss, family and hero worship, Lowery’s picture is a breathtaking meditation on the power of true, blue storytelling, told by a director who has become as assured a filmmaker as we’ve seen come along in quite some time.

As mentioned above, much of the film is told through half muttered utterances or scenes that we don’t have much, if any, context for. Instead, Lowery here has the power of his own craft to paint a poetic and lyrical meditation on the anti-hero Western myth, while itself is a film entirely about storytelling. Throughout the film characters are telling stories be it about their dreams (Affleck’s Bob spouts one of the more powerful lines near the end of the film to his wife, “let me tell you about the future”) or even a gun, for a film this sparse narratively to be so intensely interested on the act of storytelling and myth building is utterly inspired and quite breathtaking.

There is an experimental tinge to much of this film, at least in the editing, which you can tell is a stamp of the filmmaker. Harvey Weinstein had allegedly given him a few notes on how to edit the film earlier this year, but it doesn’t appear Scissorhands got ahold of this film like he did Wong Kar-Wai’s latest masterpiece The Grandmaster (and yes, the international cut is a classic in the genre). It’s a taut picture with a dream like lyricism all its own, not far removed from a Malick film, but less self-important and “silly” than say Malick’s recent and only failure, To The Wonder. It’s a picture not afraid to relish in its roughness and in that, comes its real beauty.

And boy is this film beautiful. Along with something like The Grandmaster this film is without a doubt the prettiest film of 2013, and one of the more awe-inspiring. With a score that will leave you stunned from Daniel Hart, the compositions here are impossibly powerful, playing into each scene’s emotion perfectly. The film does feel very much like a rustic return to down south aesthetics, something we’re seeing more and more with the likes of Mud rolling around, but what sets it apart here is an intimacy and an aesthetic universality that turns this period piece into a drama that feels oddly timeless. Lowery’s camera is ever so fluid and the Bradford Young-shot photography should hopefully garner his awards consideration later this year and early into 2014, but if anything, the pair make this film one of this year’s most stunning pieces of pure blooded cinema.

All this talk of a film that holds style and thematic substance in equal regard may have one thinking that the performances may be lacking. However, that couldn’t be further from the truth. Mara and Affleck are career defining here, particularly Affleck whose voice is just the right blend of off putting and yet innocent to really add depth to his character. Ben Foster steals the show here as a cop who begins to get closer and closer to Mara’s Ruth, and both Keith Carradine and Nate Parker add a lot of intrigue via smaller roles, Carradine in particular who is always a welcome face to see pop up on the big screen.

While the seemingly run-of-the-mill narrative may leave a handful of theatergoers rather underwhelmed, those who give this film a shot and go for the subsequent ride will be in for something deeply powerful. A haunting look at family, loss and the impact of storytelling, Ain’t Them Bodies Saints is a drama that verges on being considered Lowery’s first masterpiece. With an evocative title that seems to itself know that this film is nothing but a story being told to its audience, hopefully as the film begins to roll out into more theaters more people will have the chance to try and answer that question.

![Bergman Island (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/bergman-island-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/this-is-not-a-burial-its-a-resurrection-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![Lars von Trier's Europe Trilogy (The Criterion Collection) [The Element of Crime/Epidemic/Europa] [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/lars-von-triers-europe-trilogy-the-criterion-collection-the-element-of-400x496.jpg)

![Imitation of Life (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/imitation-of-life-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (The Criterion Collection) [4K UHD]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/the-adventures-of-baron-munchausen-the-criterion-collection-4k-uhd-400x496.jpg)

![Cooley High [Criterion Collection] [Blu-ray] [1975]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/cooley-high-criterion-collection-blu-ray-1975-400x496.jpg)