It’s perhaps telling that, for a good long while into the picture, I thought Stoker might be a period piece set anywhere from the 1940s to 1970s. The titular family, which has recently suffered the loss of the father, Richard (Dermot Mulroney), leaving only mother, Evelyn (Nicole Kidman), daughter, India (Mia Wasikowska), and sudden houseguest Uncle Charlie (Matthew Goode), is so deeply embedded in a certain idea of upper-class New Englad lifestyle that even they seem almost frozen. Their movements disrupt the carefully-curated-and-maintained old-money image. They also reveal what’s really there. But far from being a cheap treatise on the sick soul of wealth, Stoker is instead about the universality of repression, both from within and without, and ends up suggesting that maybe a little is a good thing. It’s also a deeply weird thriller in the vein of later Alfred Hitchcock or even later Brian De Palma, with the formal rigor naturally associated with each of them, or, for that matter, with director Park himself.

Park, a South Korean filmmaker, came to prominence on U.S. shore’s in 2005 with Oldboy, a truly demented, thoroughly engaging, revenge thriller, and ever since then, questions about his interest in working here have abounded. He’s resisted, making another three features (and a handful of shorts) in South Korea, continuing to push aesthetic and narrative boundaries, but it is only by comparison that Stoker seems in any way tame. In the landscape of American cinema, well…it stands out. Directing his actors towards a heightened performance style highlights their separateness not only from the outside world (kids at India’s high school behave more “typically”), but from one another, but it also just makes for damn engaging cinema. Innocuous sentences are turned on their head, and more suggestive statements take on exactly that meaning you’re thinking of. This isn’t a subtle mode of operation, and it’s pretty easy to see the larger game from the start, but it’s too much fun not to play, as India’s late bloom into womanhood takes on a sort of external representation of an interior turmoil.

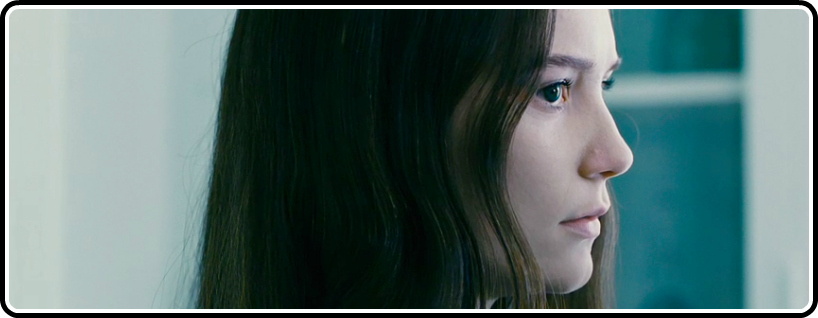

Wasikowska has been one of the more dependable young actresses these last couple of years, though in spite of having a few starring roles, she wasn’t granted a cinematic space to make the most of them (Alice in Wonderland allowed for no interior space for its lead character, while Jane Eyre was too rushed and scattershot to make use of her otherwise astute take). Wentworth Miller’s screenplay doesn’t always serve her, or her character, best, taking some too-long detours away from India’s stunted psychology, but this is easily the best she’s been, and Park makes the most of her big, beady eyes and steady mix of unease and total determination. Growing up requires a careful negotiation between who you’re told you are and who you discover yourself to be, and India’s own resultant character is such a delicate mix of the two that neither emerges as a more moral, well-rounded path, suggesting that some people are just damned.

Kidman and Goode have proven themselves extremely capable of this kind of performance style, and Kidman in particular plays with audience sympathies in some really interesting ways. Introduced to us as a woman who will probably be more cared for that caring following her husband’s death, and a little too eager to take in his younger brother, the fullness of her character is not so easily condensed, nor is it the subject of some wild reversal. She’s simply nuanced, both within herself and her place in the story, trapped very much by an identity formed by who she was told to be, and given that first, dangerous glimpse of freedom.

The uncommon intelligence Park and his stalwart cinematographer Chung Chung-hoon bring is evident right from the start; the credit sequence alone is a story unto itself, full along the way of a dozen indelible images. But it’s not just their ability to encapsulate theme, character, and story within the frame that makes them so deadly – it’s the way the frames play off of one another, not just from shot to shot but across time (the editing patterns bring this sharply into focus) and space, the very limits cinema so naturally transcends. It’s the playful quality they bring, as when they frame Goode’s head to block out an unwanted fourth party just as he asks Kidman and Wasikowska if there’s anything “you two would like to play?” Or in another dinner table scene, in which Chung throws a few extra lights in Goode’s eyes, giving him an otherworldly expression, countered sharply with the Wasikowska’s deep, unreflective own. Miller’s screenplay certainly has its share of lofty goals, but it is at its heart a twisted pleasure, and Park wisely acknowledges that the two need not be incompatible; rather, he exploits it.

The whole affair is a tightly-wrought, ecstatically demented delight, one of the year’s best so far.

![Bergman Island (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/bergman-island-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/this-is-not-a-burial-its-a-resurrection-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![Lars von Trier's Europe Trilogy (The Criterion Collection) [The Element of Crime/Epidemic/Europa] [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/lars-von-triers-europe-trilogy-the-criterion-collection-the-element-of-400x496.jpg)

![Imitation of Life (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/imitation-of-life-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (The Criterion Collection) [4K UHD]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/the-adventures-of-baron-munchausen-the-criterion-collection-4k-uhd-400x496.jpg)

![Cooley High [Criterion Collection] [Blu-ray] [1975]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/cooley-high-criterion-collection-blu-ray-1975-400x496.jpg)