More often than not, when people think of an artist adapting a work from the legendary Bard himself, William Shakespeare, they conjure up visions of stilted costume pictures with more interest in production values than truly getting to the heart of Shakespeare’s tale they are adapting. And then there are the films of Matias Pineiro.

Pineiro, a young filmmaker from Buenos Aires, has become known as much for his dream like visuals and sensual storytelling as he has his brilliant re-imaginings of Shakespearean comedies. With a short film Rosalinda and his last feature, Viola, he has begun a new project of sorts, adapting As You Like It and Twelfth Night respectively, bringing his quiet and heady filmmaking to the works of Shakespeare.

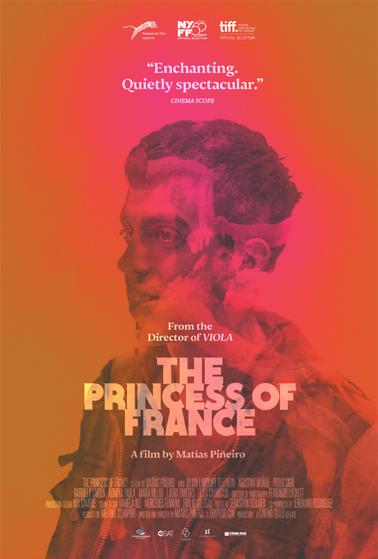

That’s where his new film comes into play. Building off of this short and feature project, Pineiro is back with one of his greatest works to date. Entitled The Princess Of France, the film takes a direct look at one of Shakespeare’s greatest and most entrancing works, Love’s Labour’s Lost, a piece that plays both as inspiration and direct plot point. Princess introduces us to Victor, a director who arrives in Buenos Aires after the death of his father. Victor has been prepping a new radio adaptation of the aforementioned play, and the film sees him getting back in touch with friends, acquaintances, past lovers, new lovers, girlfriends and actresses.

Princess Of France is a quite intriguing shift of focus for Pineiro. Despite re-teaming with his Rosalinda and Viola cast, including the likes of Maria Villar, Romina Paul and Agustina Munoz, the film is centrally focused around the male cast member, Victor, played by Julian Larquier Tellarini. While men have played parts in his previous films, this is the first work in his Shakespeare project that has a male eye at its center. It does keep the sense of artistic malaise that is drenched throughout Pineiro’s pictures, and the film finds Pineiro at his most playful, both with form and theme, as well as gender politics within art. Victor, despite being our lead however, isn’t an impactful one. Passive to the very end, Victor proves to be influenced entirely by the women floating in and out of his life, and it does foster some interesting looks at romance and youthful interactions between artists.

Clocking in at just under 70 minutes and having garnered critical acclaim on the festival circuit where it played various crowds ranging from the Toronto Film Festival to New York, the film is a brisk yet deeply rewarding watch. Pineiro is one of today’s most enthralling young talents and this is a truly crowning, breathlessly paced piece of work. Sending the viewer once again into the world of artists and intellectuals, where the narrative itself doesn’t carry much thematic weight but instead breathes effortlessly as a character and performance piece, Pineiro’s filmmaking is at its most stayed and most intimate. Allowing the camera to linger romantically on these characters all of whom are closer to one another than it may appear. With gorgeous and richly textured photography from Fernando Lockett, the film carries with it a breathtaking aesthetic that feels more like a the remembrance of a summer romance (both physically and creatively in many ways) where the lighting is a little more dim, the hues a little more rich. It’s truly an artistic achievement.

And the performances here are just as superb. Julian Larquier Tellarini is great here as our lead, Victor, a quiet young artist with a rather storied past. He floats throughout the film as almost a phantom from the past of the women in his life, and his relationship particularly with Maria Villar is quite intriguing. Villar is always a welcome addition to any film, an actress who is uncannily beautiful and yet exponentially more talented. One of today’s great young actresses, she’s an absolute joy to watch on screen. Toss in other Pineiro staples like Munoz and the stunning Laura Paredes, and you have one of the year’s great performance pieces. Given life by a lyrical, almost musical, script, and it is a true sight to be seen. In many ways, these films from Pineiro are much less adaptations of works of Shakespearean theater. Kenneth Branagh Pineiro is not. Instead, Pineiro is much more interested by the inherent nature of the theater, and the ability for it to get at truths about the human condition. There’s a sequence in this film, for example, that finds one of our characters trying to get in touch with our lead through a friend’s phone, a scene we see run its course a few times, with different results each time. It’s formalist filmmaking at its very core, and it proves to be one of the more stunning achievements in the young filmmaker’s career to date.

Despite being just a touch over an hour, few modern films that have a runtime this economical are this enthralling and dense with characterization and information. As with all of Pineiro’s previous works, Princess Of France is a beautifully composed picture that has no issue giving us details before faces. Forcing the viewer to find connections despite the entire film feeling entirely driven by impulses, this is a truly beautiful cinematic achievement that forces the viewer to have a conversation with it, or else be lost in a dream fueled by the summer heat, creativity and romance. Playful, musical and intensely romantic, Princess Of France is a must see film from a must watch filmmaker.

![Bergman Island (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/bergman-island-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/this-is-not-a-burial-its-a-resurrection-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![Lars von Trier's Europe Trilogy (The Criterion Collection) [The Element of Crime/Epidemic/Europa] [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/lars-von-triers-europe-trilogy-the-criterion-collection-the-element-of-400x496.jpg)

![Imitation of Life (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/imitation-of-life-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (The Criterion Collection) [4K UHD]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/the-adventures-of-baron-munchausen-the-criterion-collection-4k-uhd-400x496.jpg)

![Cooley High [Criterion Collection] [Blu-ray] [1975]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/cooley-high-criterion-collection-blu-ray-1975-400x496.jpg)