Greetings, CriterionCast readers. I’m writing to you today from outside my usual routine of blogging in the comfort of my own home, as I’m in the midst of a family vacation to Northern California. So this review will admittedly be on the skimpy side compared to the depths of detailed and nuanced observation I normally strive to provide. And in the case of the film at hand, that’s not such a big problem. L’enfance nue, the 1968 debut feature of French director Maurice Pialat, is a film probably best critiqued in a stripped-down manner. After all, the title translates into English as “naked youth,” though the only nudity involved is in regard to its plain, unadorned delivery: no soundtrack music, no effort at filling in a back story, no dramatic build-up, catharsis or resolution.

The youth at the center of the story is a ten year old boy, Francois Fournier, who we follow in his journey from one foster home to another and finally to a (temporary?) placement at a reform school. Francis’ impulsive nature and emotional disconnect from the consequences of his frequent destructive actions force the Social Services system to relocate him as they search for a placement that can keep him under control.

When we first see him, he’s living with a young couple, Robby and Simone Joigny, who can’t have children of their own. They already had a foster daughter, Josette, and wanted a boy to create something closer to their ideal family. Francois looked the part (he’s a handsome young boy) but his capacity for coldness and cruelty is more than they can handle, so they make their case to their worker and soon enough, he’s bundled off to a new home, the Thierrys, an older couple more experienced at working with difficult kids and possessed of a gentler nature, better able to keep Francois’ routine misbehavior in perspective than the Joignys. But even though they do manage to forge a sincere and reciprocal connection with their foster son, incorporating him into the routines and rituals of their family as best they can, it’s not enough to keep Francois on the straight and narrow.

His acting-out behavior stirs up more serious trouble and the film ends with the elderly couple receiving a note written by Francois from the institution he’s been assigned to at least for awhile to determine the extent of his psychological disturbance.

That ending-revealing summary may seem like a spoiler to some, but I’d dispute that, because L’enfance nue‘s reveals are scattered all throughout the film, not just in the scenes that occur toward its conclusion. The viewer is brought along to simply serve as a witness to an assortment of episodes involving Francois, showing us slices of his young life as it is, without adornment, explanation or sensational framing. We are pulled back and forth between viewing Francois as an irritating perpetrator of senseless violence to a likable child just on the verge of being “reached” and restored once and for all. The effect is to place us in a degree of perturbation similar to the adults trying to figure out what is in the boy’s best interest while also looking out for the welfare of his innocent victims.

Now as a close observer of Criterion’s new release announcements over the past couple of years, I have to note the lack of comment and interest that L’enfance nue generated when its inclusion to the Collection was first revealed. I figure that this relative apathy was due to the fact that few of us who routinely react to the news online had seen or even heard of this film. My first impressions were that L’enfance nue was a wistful, poignant “coming of age” story, something along the lines of Claude Berri’s admittedly sentimental The Two of Us, released the previous year. (Berri, along with Francois Truffaut, co-produced this film.) It’s not Pialat’s first Criterion title – A nos amour, from the early 80s, came out several years ago – but he’s one of the less celebrated directors to earn that distinction.

If L’enfance nue is any indication, I think that’s because he doesn’t concede much to popular tastes or the conventional demand for a satisfying emotional payoff at the end of the story, even if the feelings generated are sad, depressing or bleak. Pialat simply intends to make us aware that such situations as the one Francois finds himself in exist, and that nobody really has a solid grasp on how to resolve them. My hunch is that L’enfance nue‘s release won’t generate a huge buzz amongst the Criterion fan base, but it’s a worthy entry that I’m personally very grateful to have seen, and will return to with some frequency. For over twenty years now, I’ve worked in social services, in a residential treatment agency for youth quite similar in behavior and temperament to Francois, so I found this film especially fascinating, and completely believable. I’m even giving some consideration to how I can use it for training purposes with our clinical staff!

Besides the short (83 minutes) main feature, the DVD includes an excellent documentary from 1968 about the making of L’enfance nue featuring delightful interviews with the Thierrys, real-life foster parents who had never acted before and essentially played themselves, along with short interviews with Pialat and a pair of his collaborators, a visual essay on Pialat’s realist style and Pialat’s first film, L’amour existe, a 20-minute short from 1960 on the shallow emptiness of life in suburban Paris that I found quite fascinating.

As Criterion appears to be in the process of lowering the price of their regular DVD releases, I take it as a good sign that they’re continuing to load up on the special features. This is a rich offering that, despite being over 40 years old, provides a unique and relevant perspective on problems faced by many young people and the concerned adults trying to help them today.

I’ll finish up here on a technical note, citing Criterion’s recent explanation of the unusual yellow-tinted color scheme that was first noted by DVDBeaver.com in its comparison with the British release of L’enfance nue. My experience with this aspect of watching the film may be of some interest. I first watched the film on my home system, before reading any of the above material, and definitely noticed the jaundiced character of the image on my screen.

However, watching the film on a different system at my current vacation spot, the yellow didn’t stand out at me so much, perhaps due to some automatic color correction by the player? But I did note that the aspect ratio jumped back and forth from appearing horizontally pinched to normal on several occasions when watching both L’enfance nue and L’amour existe. The disc player was set on Automatic formatting when that happened, but after I changed the setting to Wide Screen, that problem went away. I won’t venture a guess as to whether this is constitutes a “problem” with the DVD or not, but I’m just passing along this tip in case it helps anyone else.

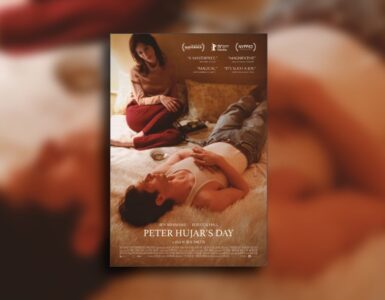

The singular French director Maurice Pialat puts his distinctive stamp on the lost-youth film with this devastating portrait of a damaged foster child. We watch as ten-year-old François (Michel Terrazon) is shuttled from one home to another, his behavior growing increasingly erratic, his bonds with his surrogate parents perennially fraught. In this, his feature debut, Pialat treats that potentially sentimental scenario with astonishing sobriety and stark realism. With its full-throttle mixture of emotionality and clear-eyed skepticism, L’enfance nue (Naked Childhood) was advance notice of one of the most masterful careers in French cinema, and remains one of Pialat’s finest works.

Disc Features

- New, restored high-definition digital transfer

- L’amour existe, director Maurice Pialat’s poetic 1960 short film about life on the outskirts of Paris

- Autour de ‘L’enfance nue,’ a fifty-minute documentary shot just after the film’s release

- Excerpts from a 1973 French television interview with Pialat

- New visual essay by critic Kent Jones on the film and Pialat’s cinematic style

- Video interview with Pialat collaborators Arlette Langmann and Patrick Grandperret

- New and improved English subtitle translation

- PLUS: A booklet featuring an essay by critic Phillip Lopate

?