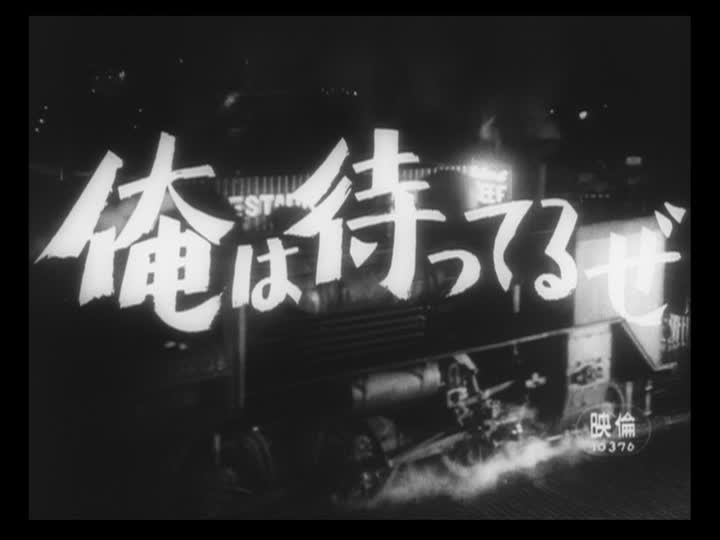

This week’s Eclipse Series review is based simply on how it lines up with the timeline of films I’m reviewing over at Criterion Reflections. This 1957 release came out right between The Cranes are Flying, which I posted on last week, and Paths of Glory, which I reviewed on this site as a new release back in October and will take another look at over the next few days. I Am Waiting is the earliest film to be collected in Eclipse Series 17: Nikkatsu Noir.

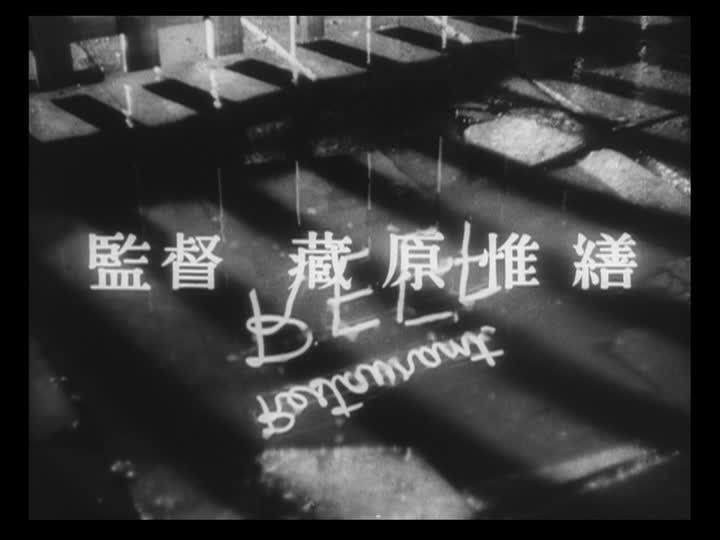

The film begins with a melancholy image of raindrops splashing in the gutter, backed up by an equally somber opening song that instantly puts us in an achy mood of longing. The tune is whistled at various times throughout the film, and you can hear it for yourself in the first 90 seconds of this medley, performed later on in life by I Am Waiting‘s star, Yujiro Ishihara. (Note: I couldn’t find any video clips from the movie itself, and embedding is disabled for this video, so this is as close to a free sample as I can provide, other than the screencaps.)

The immediate thing that struck me in watching I Am Waiting was the similarities it has with Le Notti Bianche, another 1957 film I watched a couple weeks back. I can’t assume that either film influenced the other, since they came out so close together and were shot in different countries several thousand miles apart. I’ll just blame it on the zeitgeist.

Both films open with a mass transit vehicle crossing the screen (a bus in Le Notti Bianche, a train in I Am Waiting.) They share a late-night closing-time setting, with a solitary man aimlessly wandering dark, ominously shadowed streets. He spots a lone female gazing out over the water (in Le Notti Bianche, standing on a bridge looking over a canal; in I Am Waiting, standing on the dock staring out at the ocean.) Right off the bat, each movie pulls us in by pairing up a young, attractive, intriguing and determinedly iconic couple.

That’s a timeless and universal film tradition that continues to this day, of course. Here we have Yujiro Ishihara and Mie Kitahara, reunited from the blazing hot sensation they created in Crazed Fruit, the film that triggered a youth revolt in Japanese cinema. I recommend checking out the earlier film before you watch I Am Waiting, if you get the chance, just to better enjoy their chemistry in its full culture-altering context.

Yujiro’s got that confident swagger, so cool lighting up his cigarette in the mist and wind as he befriends the mysterious beautiful stranger. Over the course of his iconic career, he established a reputation as ‘the Japanese Elvis,’ both for his sharp looks, smooth singing voice and credible turns as a marquee-worthy face who can hold his own in the action scenes.

Yujiro was a busy guy back in the day, cranking out no less than sixteen feature films between 1956-58, a ridiculous pace that Elvis himself was never able to match even in his mid-60s Hollywood prime. Sadly, both men shared another unfortunate similarity in that they both passed away too young. Yujiro succumbed to liver cancer in 1987, provoking a period of intense mourning as his fans dealt with their shock quite publicly. The date of his passing still draws an annual observance each year in Japan, much like Elvis.

His female counterpart, Mie Kitahara, beautifully forlorn in hat and trenchcoat, epitomized the late 50s ideal of young Japanese women in looks, attitude and desirability, supplanting the aging (but still beloved) Setsuko Hara as a new generation came to prominence. She and Yujiro eventually got married and she subsequently retired from making movies.

Far too little information on the rest of her life is available on the internet to satisfy my curiosity. Though she was content to lower her public profile after a few years of success, she does a great job holding our attention on screen in this film and in her other appearance in this set, Rusty Knife (reviewed here just over a month ago.)

Yujiro plays Jijo, owner of a small portside diner. Mie is Saeko, a distressed singer who’s fallen on hard times and has nowhere else to turn for help. Yielding to Jijo’s offer of shelter and protection, Saeko returns with him to Restaurant Reef, where she lets down her lustrous long black hair and reluctantly takes on the role of damsel in distress.

It turns out that she’s in trouble for smashing a ceramic pot over the forehead of a guy who tried to get fresh with her. Now she fears for the inevitable retaliation, since her attacker was a gangster’s flunky. The boss and his boys will surely track her down and teach her a lesson. But she’s willing to trust her new benefactor to keep her safe.

Far from simply trying to make it in the restaurant biz, we learn that Jijo is just biding his time. He plans to emigrate to Brazil, which must have been a fairly common desire in Japan at the time, as that idea also plays a pivotal role in Kurosawa’s I Live in Fearfrom two years earlier.

Jijo’s trying to escape his troubled past and figures that his best shot at a better future will be found in a faraway continent.

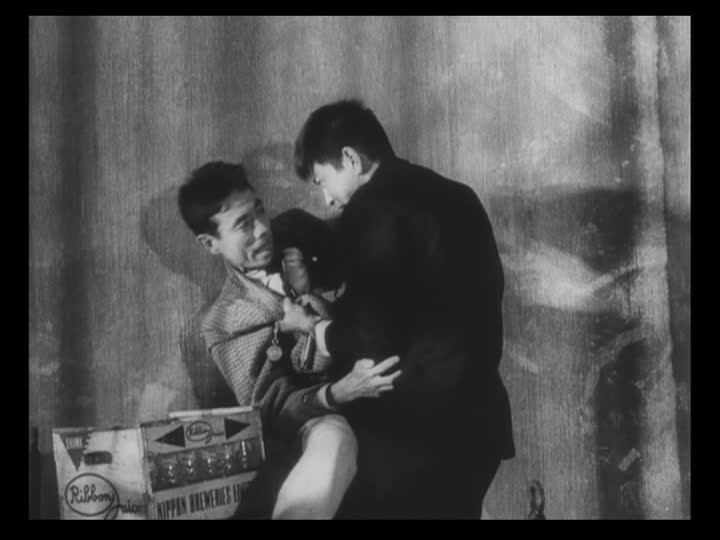

After the seeds of rescue and flirtation have been cultivated into the first sprouting of romance, it’s time for the bad dudes to show up and complicate matters. Joji and Saeko’s first date is at a boxing match, where we get our first intimations of Joji’s earlier life as a prize fighter who can no longer use his skills in the ring due to the scandal of a fatal bar brawl in which he got carried away and killed a guy with his bare fists.

When Saeko excuses herself to the powder room, she’s accosted by the hoodlum who tried to take advantage of her a few nights earlier and took a flower pot to the dome instead. Joji shows up just in the nick of time to show his nervy toughness and cement Mie’s loyalty, talking a gun out of the thug’s trembling hand without batting an eye. In the process, he learns more about Saeko’s past and troublesome ties to the mob, but that has no effect on his attraction for her. Indeed, the bond is only strengthened.

The next scene offers Saeko a chance to offer Joji some of her own consolation, as she’s the first person on hand to witness his crushing disappointment when he learns that the letters he’s been writing to his brother in Brazil have returned unopened due to ‘addressee unknown.’

His dream of getting out of Japan and starting a new life in the tropics is shattered, and now he has to pick up the pieces and make a new plan.

As the fledgling couple grapples with multiple obstacles that stand between them and a carefree life together, the melodramatic plot thickens as the local kingpin returns to make his claim on Saeko.

Joji has no choice but to capitulate, at least temporarily, due to the sheer force of numbers stacked against him. But there’s a killing machine locked up inside of him that managed to burst loose in the past and is now ready to make another appearance. Especially after he’s egged on by the unaccountable appearance in the head gangster’s hand of a medallion belonging to his missing brother at the conclusion of their first (but certainly not last) big showdown.

I Am Waitingspends its final half-hour building up to the head-cracking finale that we all know is coming as director Koreyoshi Kurahara guides us through the smoky cabarets and shadowy docksides of Yokohama at night.

He also gives Yujiro a chance to pensively strum his ukelele, which I figure must have inspired a spike in uke sales when the movie first hit theaters, if it didn’t merely reflect an already established trend.

I won’t strain myself to find some kind of big message or redeeming social value in I Am Waiting. It’s a film created primarily for the sake of entertainment (and making money) and it succeeded admirably at both tasks back in its heyday.

The degree to which today’s viewers find enjoyment in it depends on their appreciation of the unique blend of film noir conventions in the urban Japanese setting. I had a blast watching the tough guys snarl at each other before finally rolling up their sleeves and duking it out!

I Am Waitingstands at a turning point in Japanese cinema, the beginning of a subgenre that would grow more adventurous and outlandish in comparison to what Kurahara put on screen here.

It marks the moment in which Japan’s pop culture embraced overt Westernization not simply for the sake of export but for primarily domestic consumption.

2 comments