A few weeks ago I began a four-part miniseries here, reviewing Eclipse films that deal with the topic of marriage. My first selection was Ernst Lubitsch’s One Hour With You, published almost exactly a year after I covered a different Lubitsch film, Monte Carlo here in this same column.

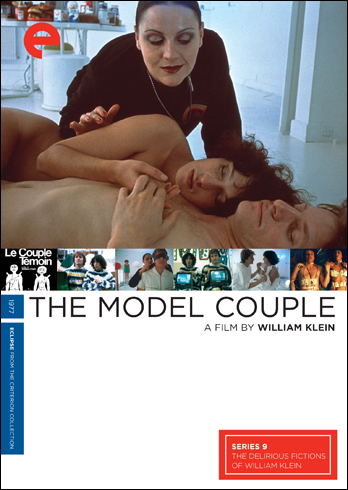

Now, even though I ran out of time to complete the series in June as I originally intended, the concluding installment, The Model Couple from Eclipse Series 9: The Delirious Fictions of William Klein, is unleashed one year after Mr. Freedom was the object of my attention over the Independence Day holiday weekend. I don’t know that these coincidences portend any particularly deep meaning, but they provide a lead into this review, so as far as I’m concerned, they serve a purpose.

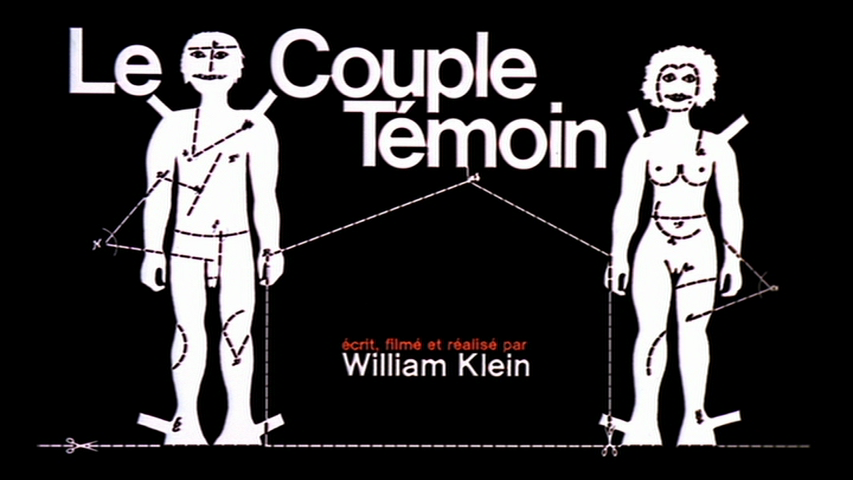

Better yet, The Model Couple also makes a great follow-up to last week’s film, Allan King’s A Married Couple. In that “actuality drama,” a real-life couple willingly subjected themselves to 100 hours of filming over the course of 2 1/2 months of their private domestic lives, providing a startling glimpse into intimate, emotionally wrenching moments of a marriage in the midst of a serious crisis. One of the significant motives that drove Billy and Antoinette was their belief, in that anything-goes experimentalist mindset so common in the late 1960s, that the process of being filmed would actually help them resolve their problems. In The Model Couple‘s “delirious fiction,” a similar premise, of a young couple voluntarily undergoing intense media scrutiny for experimental purposes, fuels the scenario. Except here, it’s not the couple who set the rules but rather a bizarre government-sponsored research entity that intends to use the information gathered to establish guidelines for achieving maximum happiness in the populace they seek to manage.

Whereas King was actively engaged in a sincere exploration of innovative application of media technologies, Klein’s approach is more jaded, cynical and satirical, intent on pointing out the inherent flaws of putting real people into highly artificial and stressful situations in order to help them lead more fulfilling “normal” lives. The difference in their two approaches are attributable in part to their respective temperaments and methodologies, as well as the passage of time and the evolution of attitudes toward comprehensive social experimentation that took place as mid-20th century confidence in progressive modernism gave way to late 20th century postmodern skepticism.

The couple, Claudine and Jean-Michel, arrive on the grounds of a massive construction site, a large-scale urban renewal project where almost everything is work-in-progress and no one has a solid grasp of what’s actually going on.

Recruited by the Ministry of the Future to the task because they so ideally fit the profile of “average users in the year 2000,” they enter into the new environment with a naive exuberance that very quickly is put to the test as they experience the dehumanizing, antiseptic and absurd protocols that have been designed to yield a particular outcome.

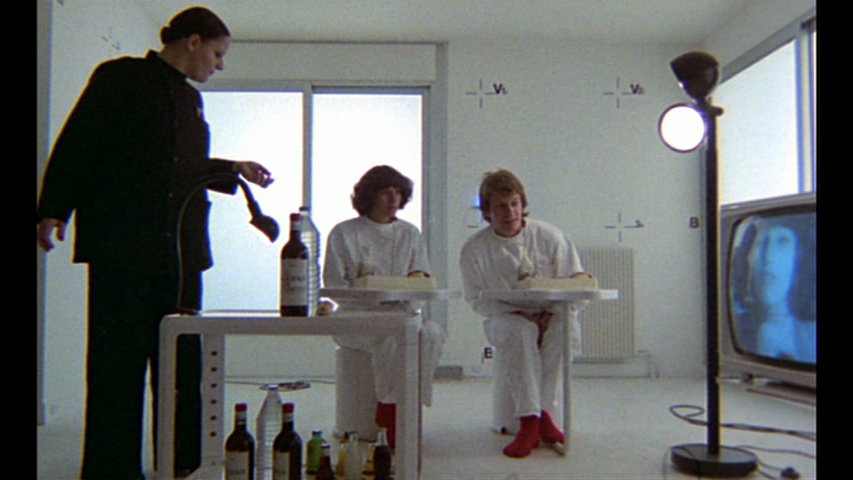

For the sake of science, a pair of black-clad psychosociologists, along with their crew of underlings, are assigned the task of managing conditions of the experiment and recording the couple’s response to all manner of stimuli, from directions to “be happy, love each other,” to their choices of breakfast foods, household appliances and consumer products.

For the sake of popular entertainment and gauging public response, the trials of Jean-Michel and Claudine are also presented in a TV documentary format, complete with glib commentary by an oily know-it-all who occupies the host’s chair with a smug sense of authority.

Set up in their apartment, barely furnished at first and bereft of all decoration except for abstractly coded “reference points,” the couple is put through a gauntlet of tests and encounters that seem intended to yield some kind of data, the use of which is never all that clear to the viewer, or even to the technicians in charge of tracking their reactions. It’s all pretty heavy-handed satirical stuff, generating most of its laughs and holding our interest more from the cartoonish visual audacity that Klein brings to his films than any pointed display of wit or social commentary.

It’s a safe assertion to say that the degree of enjoyment viewers would get from The Model Couple or any of the other films in this set depends on how much they relate to his disillusionment with the vapidity of mass media, consumer-driven marketing campaigns and the apparent helplessness of the general public to fundamentally alter mechanisms that keep placing cynical manipulators and soulless bureaucrats in positions of power and influence.

As a film about marriage, I admit that The Model Couple is rather over-burdened with broad jabs at The System and a story line that quickly grows so convoluted and outlandish that there’s little point in summarizing it here, or drawing too profound a message on what makes a marriage succeed. However, I think it’s trustworthy advice to avoid putting one’s personal life in the hands of a bunch of media handlers and lab technicians!

Still, Claudine and Jean-Michel come across as sympathetic characters, an attractively average young couple who, like so many others, easily get sidetracked and begin to flounder in the early years of building their life together as they move past the stages of infatuation and absorption in each other and on to figuring out what to do with the rest of their lives. There’s not much about what we see them go through on screen that bears direct resemblance to what most couples experience, but the stress and fatigue that comes with being pushed through the competitive economic wringers and other oppressive structures associated with technologically advanced civilization is a feeling that most if not all of us can relate to in our own way.

Klein has a lot of fun pointing out the futility of extracting objectively reliable information on human nature and behavior through the kind of loony tests and measurements imposed by the nameless psychosociologists. Even those technocrats who seek to portray themselves as emotionless, purely rational and above the petty concerns of the ordinary muckalucks they oversee and classify turn out to be as culpable to boredom, jealousy and careerist ambition as any of us. As they condescendingly scold their test subjects Jean-Michel and Claudine for failure to cooperate or expressing annoyance at the ill-timed intrusions into their private moments, behind the scenes the two psychosociologists are caught feuding with each other, complaining about the unpaid overtime and terminal boredom of their never-ending research.

In the end, they become so confused and disoriented by their own torrent of mind games that they become unreliable witnesses themselves, self-consciously faking their own desire to subvert The System in order to win the confidence of The Model Couple and in the process stoking the fires of conflict between Jean-Michel and Claudine that leads to bickering reminiscent of Billy and Antoinette Edwards (from A Married Couple.) Their arguments and rebellion soon cause the whole experiment to fail… the intended result which the experiment was originally designed to produce in the first place…!…?

In a way, the fiasco that proceeds from this overheated mess of centralized planning at cross-purposes with itself isn’t all that different from the engineered outcomes of so many reality TV shows that revolve around injecting assorted stressors and attractors into relationships between physically attractive people that cause them to break down and resort to crude reactive behaviors for the sake of mass entertainment – a peculiar notion on its own terms, but clearly a staple of 21st century vicarious living.

Klein takes a more overtly political approach in The Model Couple‘s second half, introducing a panel of government VIPs to intrude on the project and do their meddlesome, vaguely creepy thing as they flirt with Claudine and flaunt their power to the helplessly impotent Jean-Michel. The provocations push our dear young pair to the snapping point as they realize the extent to which they’ve been ripped off and exploited. But things get truly anarchic when the City of the Future, of which this experiment is just a small part, gets overrun by a gang of juvenile terrorists who barge into the apartment and hold Jean-Michel and Claudine hostage.

The stand-off ramps up the spectacle to a hysterical boil of radical sloganeering, colorful graffiti art and a ragged aesthetic that fits right in with the DIY punk ethos of 1977, the year that The Model Couple was released.

But that’s right where the story ends, with our charming young protagonists now kicked out of their home, without the benefit of government backing that sustained them and probably out of favor with the bourgeois bosses at their old jobs who watched the whole sordid spectacle unfold on their living room television sets.

Discarded by the society that raised them with promises of all the benefits that come with the assumptions of adult responsibility, Jean-Michel and Claudine are left alone, a postmodern Adam and Eve cast out of the technological paradise that The System had prepared for them, stripped of their innocence and left to forage their way, alone together, in the wasteland of the world that awaits.

Just for a sample of Klein’s style, here’s a fun clip I found that functions almost like a short music video, featuring Claudine and Jean-Michel in the early stages of the experiment as they dash from one mood to another over the course of a few meals.