After spending a lot of time last week watching and thinking about Yojimbo, Akira Kurosawa’s enduringly influential samurai action-comedy from 1961, I decided to take my next step on this journey through the Eclipse Series back to the very beginning of that great director’s career. His first film, Sanshiro Sugata, shares a fair number of common traits with Yojimbo – they both proved so successful that they inspired a sequel, for example – but also, not surprisingly, some revealing differences that reflect Kurosawa’s development as an artist and a human being. Given all that Kurosawa had observed and achieved over that nearly 20 year span, a most pivotal epoch in Japanese history, comparisons between the two films’ protagonists and how they embody Kurosawa’s views at their respective points in time indicate a tempering of his youthful idealism and a wizened sense of diminished expectations regarding the possibility of constructive social reform.

I first encountered Sanshiro Sugata in the summer of 2010, when I briefly reviewed it here along with the rest of Eclipse Series 23: The First Films of Akira Kurosawa. At the time, I enjoyed the set overall as a valuable record of Kurosawa’s earliest work, but I don’t think I was as enthusiastic about the films themselves as I am now, after digging deeper into this first title following my study of Yojimbo. Truly, Kurosawa’s technical skills are nowhere near as refined as they became in the 1950s and beyond, and in the case of Sanshiro Sugata, we’re also dealing with a film that was truncated by Japan’s wartime censors, with seventeen minutes of footage lost forever, so we can’t even see Kurosawa’s original vision on the screen (though a script is still available.) But what remains visible is a virtual seedbed of themes and cinematic methods that Kurosawa would go on to cultivate over the next several decades. Cut him some slack for limited budgets and some irreparable damage to the surviving prints and I think any Kurosawa fan will find a lot to appreciate about his debut feature.

Sanshiro Sugata‘s title comes from the name of its lead character, a young man who, like the nameless figure at the center of Yojimbo (who only becomes “Sanjuro” on the spur of the moment, out of necessity when pressed by his hosts,) arrives in town with an unknown past and an uncertain future. The big difference here is that Sanshiro’s town of choice is Tokyo, not some dusty crossroads village, and he has a clearer intention than Sanjuro for making the journey. He’s come to the big city to get martial arts training, specifically jujitsu, techniques based on throwing opponents off balance rather than striking them with fists or feet or using weapons. The film is loosely based on a historic character who went on to become famous for his own athletic exploits, but since the name Sanshiro Sugata doesn’t really communicate much to viewers unfamiliar with that lore, the film was also known as Judo Saga.

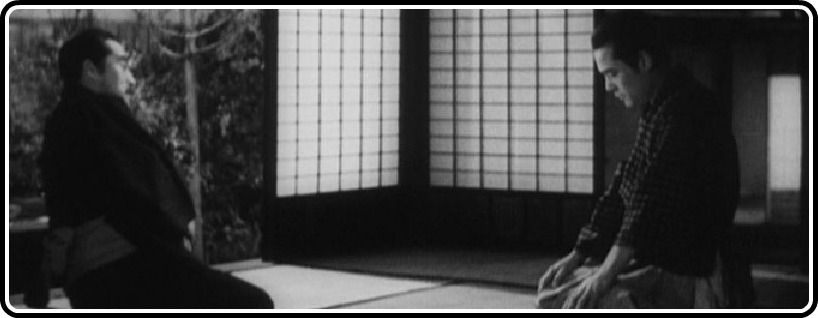

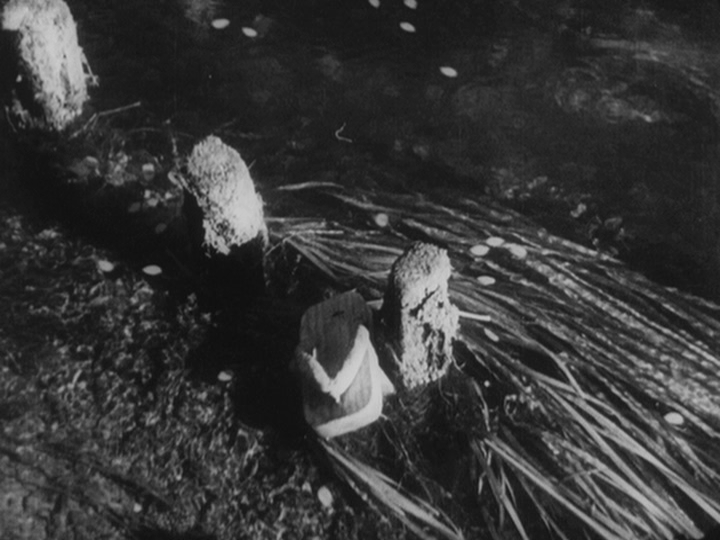

Sanshiro’s path leads him to fall in with a gang of toughs led by a jujitsu fighter named Momma (that’s pronounced with a long O sound, and I’ll let you supply your own “yo momma” jokes, if it suits you.) He and his crew have a grudge with Yano, who’s developed a competing variation on jujitsu he calls judo. Like any group with strong territorial instincts, they sense a threat when a new idea comes along and they aim to do something about it by ambushing Yano on a dark evening. We’re quickly thrust right into the first big action sequence of Kurosawa’s career and it’s a pretty cool one as the middle-aged Yano impassively takes on each of the younger men, standing on the edge of the waterfront, tossing them all in the drink as he stoically demonstrates the superiority of his techniques.

I found the grim, nearly silent hand-to-hand style of fighting oddly fascinating, a nice change from the loud high-impact clashes that usually take place in the movies when two or more angry men resort to brute strength to settle their conflict. The dark shadowy setting on a deserted wharf, without dramatic musical accompaniment to cue our emotional response, lends a palpable tension to the scene. We feel the stiffness of bone and muscle as each man pushes hard, feeling for that brief moment of buckling under pressure that will allow them to get the upper hand on the adversary. Yano’s deadly seriousness impresses the viewer almost as much as it astounds Sanshiro himself, who immediately realizes that here is the master teacher he’s been looking for.

In his haste to part ways with Momma’s gang, Sanshiro offers his services as Yano’s rickshaw driver and in the process kicks off his geta footwear, since they are of no use when pulling the one-man carriage. That discarded sandal becomes a motif used by Kurosawa in the above sequence to indicate the passage of time and change of seasons, ultimately ending up floating down a river that passes by the compound where, under Yano’s tutelage, Sanshiro has been steadily growing his strength and endurance, along with his ego and a sense of invincibility. Like many a young man before and since, Sanshiro is seduced by the power of his impressive talents, putting his newly-acquired judo skills to work as a common street brawler who’s eager to show off and push around guys even bigger than him. That unseemly demonstration leads to a fall from Yano’s favor, and he’s sternly chastised by the sensei –a harsh rebuke that inflicts emotional pain but turns out to be a necessary setback on the road to Sanshiro’s eventual enlightenment. Kurosawa can hardly be credited with inventing this ancient theme, but he captures the process of repentance and Sanshiro’s epiphany quite effectively in the clip below:

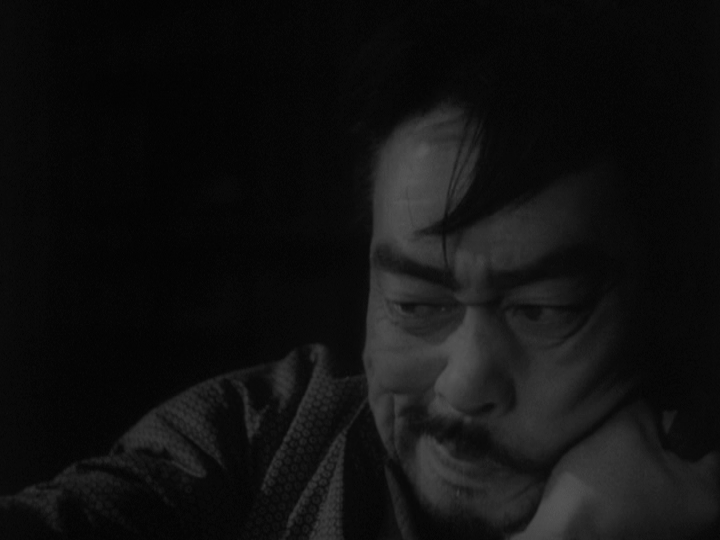

The end of the scene also introduces Sanshiro’s eventual rival Higaki, whose Guy Fawkes-like countenance and decidedly Western wardrobe clearly distinguish him as the film’s main villain. Unlike the brutish and simple-minded Momma, who can’t handle being shown up by an older outsider (his yelp of defeat, “Kill me now!” after Yano pins him down, still reverberates today,) Higaki is a malevolent schemer who seeks to inflict death and destruction on anyone who casts a shadow on his own sense of supremacy. After he’s denied the opportunity to challenge Sanshiro directly due to disciplinary limitations placed by Yano on his young protege, Higaki nurses his grudge, patiently awaiting his opportunity to avenge the insult he perceived from being turned away.

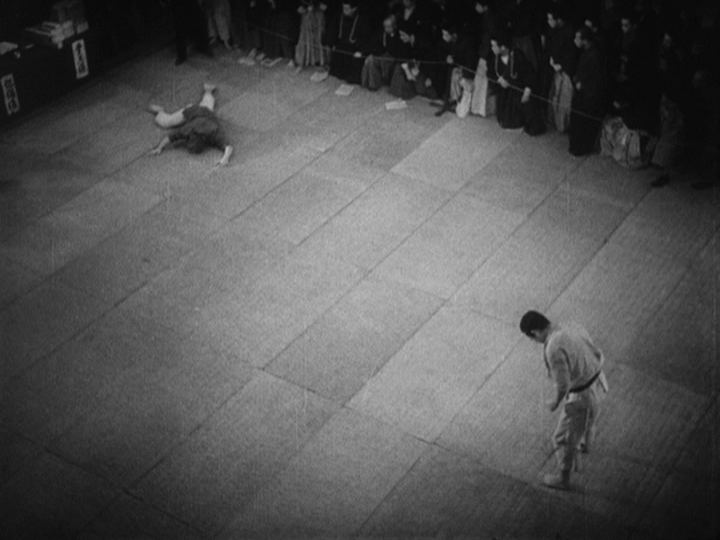

With Sanshiro back in Yano’s good graces, and showing promise as a master of judo, he’s chosen to demonstrate the techniques at a contest sponsored by the local police, who will employ the winner’s dojo leader as their instructors. The competition pits Momma against Sanshiro, and that leads to a wonderful sequence that I’ve laid out in a long series of screencaps below. It serves as a revealing demonstration of Kurosawa’s early embrace of the visual flourishes he became so famous for in many a classic to follow.

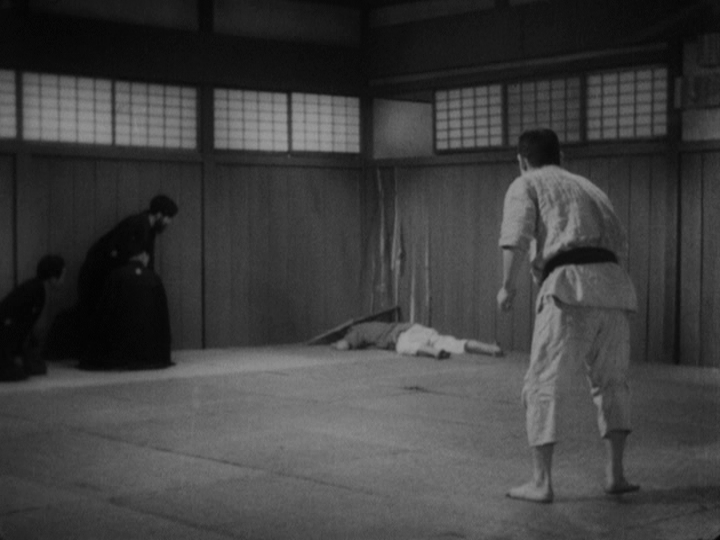

After twirling around the floor for several turns, Sanshiro seizes his moment, grabbing Momma…

… tossing him across the room wildly with brutal ferocity, to the astonishment of all present.

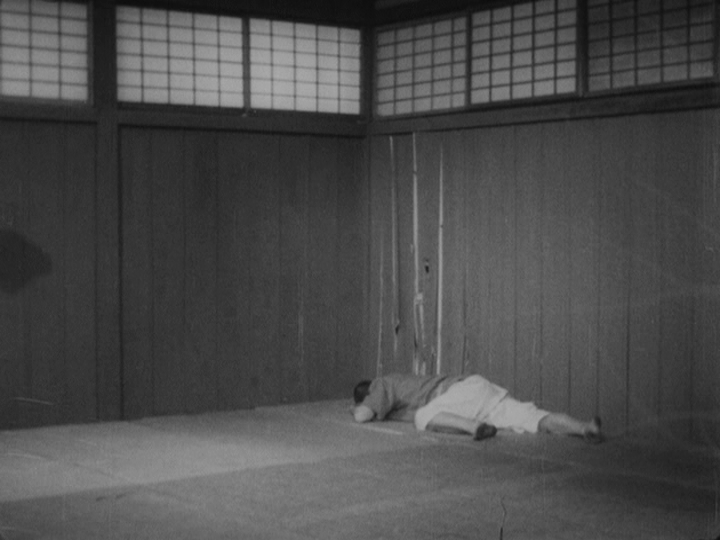

The room falls deathly silent as Momma’s body lays immobile, smashed into the corner with such force as to crack the paneling…

… and loosen the window frame which drops in slow motion over his prone and motionless head.

The silence remains unbroken until a single piercing scream erupts, a woman’s voice…

… then that too grows quiet, leaving only the hard, hateful stare of Osumi, Momma’s daughter, who has just witnessed her father’s death.

Though a few of the cuts are choppy (perhaps due to censorship, limited resources, deteriorated film stock, or simple inexperience), it’s still a very auspicious demonstration of Kurosawa’s flair for dramatic scene-craft and fearlessness when it came to staging a big moment on the screen.

Back to the lounging, decadent Higaki for a few moments… I love the image of him flicking cigarette ashes directly into the rosebud.

The scenes that suffered the most cuts appear to be those involving the two main women in the film, the vengeful Osumi, who’s caught with a knife, intent on assassinating Sanshiro, and Sayo, the daughter of Sanshiro’s next opponent, the aging jujitsu master Murai who taught Higaki and considers him one of his best pupils, despite the sinister aspects of his personality. It’s a shame that we didn’t see more of these subplots, because they apparently played important roles in Sanshiro’s spiritual maturity. First he has to deal with the unsettling contempt of Momma’s daughter, then he’s forced to reckon with the purity of heart shown by Sayo as she earnestly prays for her father’s victory in his next match, not knowing that the handsome young man she’s taken a liking to will soon be facing off in a winner-take-all showdown.

Murai is played by Takashi Shimura, soon to become the mainstay of Kurosawa’s early career, much like Toshiro Mifune was the go-to guy in Kurosawa’s middle period before Tatsuya Nakadai took Mifune’s place in the last phase of his work. The fight scene between Murai and Sanshiro is another well-executed bout, with touches of humor (when Sanshiro lands in a referee’s chair after fending off Murai’s toss) and the trademark physical gestures that Kurosawa often instructed his actors to use to convey personality (here, it’s head-rubbing; in Yojimbo, it’s hitching shoulders.) Again it ends with a ferocious throw by Sanshiro, but this time his opponent lives. Murai even pays his respects afterward, seeing in the young fighter a foe most worthy of holding the torch he’s ready to pass.

But of course, we can’t just applaud the champion and be done with it… not while there’s a seething spite-fueled enemy out there plotting his demise. Sanshiro Sugata needs a big epic finale, and Kurosawa delivers magnificently, at least in the scale of its setting, a broad windswept mountain meadow where Higaki, a priest who serves as referee and mediator, and Sanshiro show up on cue to settle things between them. The fight itself may leave a bit to be desired, with the most acrobatic moves typically interrupted almost as in cartoons where the violent moments of impact take place off the screen, with reaction shots serving notice that something dreadful has just taken place. But Kurosawa’s framing, and even the blurry opacity of the images themselves, hold a conducive power. The last shot, probably hard to make out clearly here, of Higaki’s inert body sliding head-first down the hill, is impressively climactic.

Like Yojimbo, Sanshiro Sugata wasn’t originally intended to be the first of a two-part series, but public acclaim was such that Kurosawa was quickly given the assignment to bring back his popular characters to build on those successes. The jaded and cynical ronin Sanjuro, who pits greed vs. corruption, foolishness against malice, who has honed incredible skills and calls no man his master, stands as a proxy for the older Kurosawa, who’s unable to deliver such a plaintive and optimistically hopeful message as he did in his earlier works, but still has plenty to say about what he doesn’t like as he surveys what’s happening all around him in Japan’s postwar economic boom.

Flash back eighteen years or so, as Japan’s imperial order fights feverishly to stave off its own demise. In the midst of that turbulent and uncertain time, Sanshiro’s quest to learn and eventually master a new discipline and to tame his raw instinctive abilities for the sake of serving a noble purpose marked a course that Kurosawa himself would follow for at least the next decade or so of his life. The young disciple, just emerging from his apprenticeship and standing on his own as a first-time director, was still playing it safe at this point, making sure his hero got the girl at the end, sending them into the future on a spiffy steam engine train. Sanjuro’s lonely walk out of town at the end of Yojimbo, as iconic as it eventually became, wasn’t quite ready for Kurosawa to offer at this stage. He would require a few more battle-scars before he could render it convincingly.

![Bergman Island (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/bergman-island-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/this-is-not-a-burial-its-a-resurrection-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![Lars von Trier's Europe Trilogy (The Criterion Collection) [The Element of Crime/Epidemic/Europa] [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/lars-von-triers-europe-trilogy-the-criterion-collection-the-element-of-400x496.jpg)

![Imitation of Life (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/imitation-of-life-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (The Criterion Collection) [4K UHD]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/the-adventures-of-baron-munchausen-the-criterion-collection-4k-uhd-400x496.jpg)

![Cooley High [Criterion Collection] [Blu-ray] [1975]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/cooley-high-criterion-collection-blu-ray-1975-400x496.jpg)

1 comment