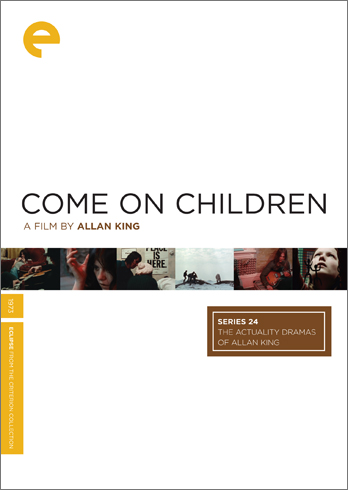

This week’s installment in my long and winding Journey Through the Eclipse Series coincides with my most recent venture here at CriterionCast as co-host of The Eclipse Viewer podcast. Yesterday, Robert Nishimura got together with our prolific news writer and reviewer Josh Brunsting to discuss the first three films found in Eclipse Series 24: The Actuality Dramas of Allan King. Given the substantial heft of the five titles in that box, and more than three decades that separate those three from the last two, it made sense for us to split the program into two parts. So I’m looking forward to picking up where we left off next weekend. But unlike the other Eclipse sets we’ve discussed so far in our fledgling podcast project, there are a couple films I haven’t yet reviewed here, so this column (and my next) are dedicated to remedying that situation, by providing a landing space for the link I typically include in our show notes page. This write-up of 1973’s Come On Children also gives me a chance to cover a few points that didn’t come up in the conversation, and share a few images and video clips from the film.

Come On Children represents Allan King’s effort to reclaim the momentum and commercial success of his breakthrough project Warrendale. After the disappointing feedback he received for A Married Couple, a film that Josh and I in particular found quite riveting but didn’t fare so well among its contemporary audience, King decided to revisit the troubled teenager subculture that made Warrendale so compelling. Playing off the rumbling echoes of the hippie-era generational conflicts that roiled North American society as the 60s turned into the 70s, King took it upon himself to construct the circumstances in which his subjects would react and be filmed.

Rather than eavesdropping on the incidental conflicts that occur in a residential treatment program or a particularly volatile marriage, Come On Children plays out as a forced issue in which ten teenagers are given free rein over a rural Canadian farmstead for 2 1/2 months. The house is stocked with food, some kind of cash stipend is provided and all the utility bills are paid. All the kids have to do is figure out how to get along, now that the meddlesome and tedious intrusion of parents, teachers and all other adult authority figures has been magically eliminated, for a season anyway. Despite King’s heavier hand in creating the set and setting of this film than he exercised in its predecessors, the three features find some continuity in that they each represent an attempt to do something bold and innovative in response to common social and relational conflicts.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UF1w5q14AEU?rel=0]

This clip shows the beginning of the film, as the group of five young men and five young women first move in and take over the place. As usual with an Allan King film, there’s really not much in the way of exposition as to where these kids come from, whether or not any of them knew each other prior to the filming, or if any particular expectations had been given to them regarding their behavior and the role they would play in this impromptu community. Throughout the course of the film, we only learn small scraps of information about them as individuals. Come On Children offers little in terms of character study, keeping its focus more on how individuals in the group respond in the moment and, to a limited extent, give voice to some of the representative attitudes and opinions that prevailed among members of that generation on issues like parenting, birth control, abortion, the purpose and value of formal education, and so on. There’s not much discussion of politics, race relations, war or heavier topics – at least, little of that made it into King’s final cut. Maybe the fact that these are Canadians, not residents of the USA, took some of that more militant edge off the conversation.

The experiment starts off carefree and groovy enough, with some happy music making and an all-around mellow vibe permeating the place. No doubt that atmosphere was enhanced by an abundant stash of weed and other chemical compounds, all of which are ingested openly and without any overt inhibition , even though that took some getting used to by the two guys pictured above, not quite accustomed to getting their good buzz on with a cameraman perched over in the corner recording all the action.

After some period of days or weeks, the temporary residents of a farm named Froo find it within their comfort zone to indulge in some of the harder stuff, more or less oblivious to the film crew. Though the drug use is unblinkingly documented with a rather matter-of-fact plainness, there’s no lingering on what happens at the moment that Alan (pictured above) takes his hit of heroin. King’s editorial discretion serves him and the audience well, refraining from either a gratuitously moralizing or luridly exploitative stance. In other words, there are no theatrical or visual effects trying to recreate the altered perceptions and expanded consciousness of kids under the influence, nor are viewers overtly led to draw any conclusions on the net positive or negative effects of recreational drug use.

One of the most significant reasons behind Come On Children‘s enduring reputation as a landmark documentary is that it has footage of Alex Lifeson, future guitarist for the Canadian prog-rock band Rush, back when he was only 17 years old and still going by his birth name of Alex Zivojinovich. Though I’m not a big fan of the band myself (a quick check of my mp3 collection shows that I only have one song of theirs among over 50,000 other tracks), I’m certainly familiar with his virtuosity with the axe, and he definitely gets to show off both his acoustic and electric skills on a few occasions throughout the film. What’s even more fascinating though is to see the future guitar god moping around his household in full-blown sullen adolescent mode, barking at his peers (deservedly) for their neglect of basic sanitation and other aspects of life in the commune that he found uncomfortable. One gets the sense that he feels stuck in what he thought was going to be a pretty cool situation when he first got recruited. And if that’s the case, it’s also clear that his sense of entitlement was coupled with a drive to succeed that helped him perfect his musical ability to a very high level.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q7zLCw5xy_w?rel=0]

Also playing a key role in Lifeson’s future development was, no doubt, the pressure put on him by his parents in the memorable exchange captured in the above clip. In it, we see them pushing Alex quite publicly in front of his friends to stay in school and make something of himself, even though Alex sees no point in it and has no intention of even finishing high school, since he’s confident that he can get by just fine making 80 bucks a night (Canadian) playing rock’n’roll gigs when he gets back to Toronto. Whether or not you dig the music of Rush all that much, those of us who ever took it upon ourselves to “drop out” merely for the sake of dumping meaningless expectations imposed by others can look to Alex as a hero for defying the odds and proving the establishment wrong… at least in this one instance.

And speaking of parents… that visit from Mr. and Mrs. Zivojinovich was part of a family night that occurs after the kids have been in charge of the house for awhile, kind of a wake-up call to the youngsters that the time in their idyll was running down, that a more ordinary reality would soon force a return to the roles they’d temporarily abandoned. Check out the expression on both the mom’s face as she beholds this hippie-fied environment, and the daughter’s as she figures she’ll shortly have some explaining to do. As a person who’s been on both sides of these reckonings, I found a lot to enjoy in this section of the film, as the generations get to encounter each other in full bloom, so to speak and we get to dip into the confrontation.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h6qte5DHQy8?rel=0]

Beyond King’s decision to employ more artifice in creating this film than a more rigorous adoption of cinema verite ideals would allow, Come On Children is also subject to criticism for the fact that nothing particularly galvanizing takes place over the course of the film, certainly nothing that compares with Warrendale‘s footage involving the childrens’ response to the death of Dorothy or the cathartic conflicts that erupt between Billy and Antoinette in A Married Couple. Basically, the experiment runs its course, with the net result being that some well-worn axioms about the ability of teenagers to adequately care for themselves (or not) get enough reinforcement to uphold previously held beliefs on all sides of the debate. My enjoyment of the film is based more on a nostalgia for the period. I was around 10 years old when it was shot, so the music, the cultural relics, the tacky fashions all carry a lot of charm. Ultimately, I think King was smart to cast young folks with some musical talent, as John Hamilton demonstrates in his moving rendition of “Mr. Bojangles” in the above clip (nicely accompanied by Leslie on flute and Alex on acoustic guitar.) Come On Children would be a much drier, sterile film without them.

So for all its squalor, aimlessness and a potentially dangerous endorsement of behaviors that have gotten a lot of people in trouble over the subsequent decades, Come On Children holds value to me as a wistful “feel-good” experience of a bygone time – an exploration of an idea, acting upon a hypothesis that maybe kids who were coming of age toward the tail end of the Baby Boom had learned a few things from the mistakes made by their older brothers and sisters. It turns out that… nah, not really. The main lesson learned is that with an ideal set-up, you can fly kinda high for awhile, but you still want to have a comfortable and capable landing strip when the time comes to crash.