Continuing my holiday weekend indulgence in Eclipse Series 36: Three Wicked Melodramas from Gainsborough Pictures:

After the resounding success of The Man in Grey‘s bombastic take on historically-based soap opera, the Gainsborough studio chiefs ordered up more of the same, and plenty of it. Relying heavily on their talented and versatile crew of actors under contract, Madonna of the Seven Moons made for a great follow-up. Its Italian setting (of course, all filmed on studio sets in London) provided the right opportunity to break out the baroque ornamentation, lavish floral arrangements, elegant gowns and lace, along with a vital injection of Gypsy abandon, Carnival madness and Bohemian rascality to spice things up. All that window dressing is there for our visual enjoyment (for those who admire such adornments) but what holds the film together and makes it worthy of deeper examination is its portrayal (bold and shocking for its times) of a woman torn between two irreconcilable impulses of what her life ought to be.

Like all three films in this Eclipse set, the source material for Madonna of the Seven Moons was written by a woman, in this case, novelist Margery Lawrence who specialized in ghost stories, fantasy and detective fiction in the 1920s-40s. Her interest in spiritualism and speculative horror proved to be a ripe field of harvest in this particular case, though as far as I can tell, only one of her other works was ever adapted for the screen – a novel titled The Red Heels, released in Austria in 1925, directed by Michael Curtiz, and starring Lili Damita, future wife of Errol Flynn. Both stories revolve around women with a touch of scandal in their past, who allow themselves to settle into tamed domesticity, only to relapse into lewdness after being too good for too long. It seems like Margery Lawrence was working through some of her own issues by way of fiction, as is so often the case.

A note of interest here is that Madonna of the Seven Moons was the first film directed by Arthur Crabtree, whose future work includes the Criterion release Fiend Without a Face (subject of a recent CriterionCast episode) and another semi-famous schlockfest, Horrors of the Black Museum, both filmed at the tail end of his career. I suppose after those two movies, Crabtree had expressed all that he had to say in cinema. While there’s nothing remotely gory going on here, Crabtree does show an early gift for capturing lead actress Phyllis Calvert’s numerous expressions of shock and intense psychic dissociation throughout the film, establishing at least that visual link from one end of his oeuvre to the other.

After the opening credits roll, we’re plunged straight into the story of Maddalena. We first see her as a youthful innocent (with Phyllis Calvert done up in pigtails and her best Little Red Riding Hood attire to disguise her obvious maturity.) She’s alone in the woods, gathering wildflowers in her basket when a stranger wordlessly approaches her and begins chasing her with savage intent. She runs away as fast as she can, but it’s clear by the fade to black and the fade back in that she’s been raped and ruined… a tarnished girl, whose traumatic experience will come back to haunt her, despite her most earnest investment in the consolations of Catholic piety at the orphanage in which she was raised.

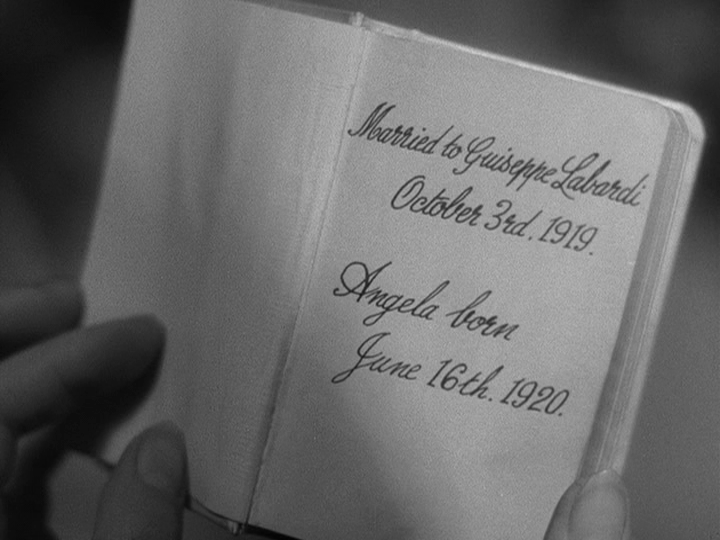

Calvert’s graceful demeanor and wholesome, almost ethereal visage made her an ideal casting choice for the virtuous “good girl,” a role she excelled at in The Man in Grey, in which she played the trusting soul Clarissa so callously betrayed by her supposed friend Hesther. Her follow-up to that film, Fanny by Gaslight (another Gainsborough Picture, not part of this set but available to watch on YouTube), further established Calvert as a reliable “under-appreciated martyr” type. For the audience that came to this film already familiar with Calvert’s basic screen persona, it was only natural to see her continue on in that vein as Maddalena finds herself called out from the Catholic girls’ school by her Mother Superior to become the genteel bride of Giuseppe Labardi a distinguished and rich Italian businessman. Her diary indicates that she was impregnated on her wedding night and thrust immediately into the responsibilities of motherhood, with hardly any time to heal from the scars of being sexually abused, let alone establish herself as an independent woman capable of choosing her own priorities in life. Still, from all appearances, she’s turned out quite well – a model wife living in enviable comfort and serenity.

The story jumps forward to the late 1930s, when Maddelena’s world is rocked by the return of her teenage daughter Angela from five years away at boarding school. Far from growing up to be as chaste and devout as her mother, Angela is thoroughly and unapologetically modern – helping herself to cocktails from her fathers’s tray, traveling by herself in the company of men and giving her newly acquainted male companion a kiss full on the mouth, right in front of Mum! Clearly, the world is changing all around the prim and proper Maddalena, who hardly knows what to make of it all.

But Maddalena is harboring a deep, dark secret – so firmly repressed that she herself doesn’t even know it! Somehow, in reaction to that horrible day in the woods, a parallel identity has been lurking below Maddalena’s surface for all these years – a woman who calls herself Rosanna, who erupts into life and takes hold of Maddalena’s body – and its long-denied passions – every so often. Apparently the transformation is triggered by a certain set of earrings, golden gaudy hoops adorned with gaily glittering crescent moons… seven of them, to be exact.

When Rosanna’s in charge, Maddalena and her prim modesty are utterly banished, as she flees the Labardi estate and rushes headlong into the arms of her roguishly charming lover Nino, a jewel thief who runs a street gang in the dangerous streets of Florence.

Even though the Florentine episodes are meant to illustrate Maddalena in her regrettably fallen condition, overtaken by the spirit (as it were) of Rosanna, loose morals and all, they’re easily the most amusing parts of the film and, more importantly, the times in which we see the woman most at ease and comfortable with herself. Clearly, there’s something a bit more invigorating to be experienced cavorting with Nino (Stewart Granger) despite the risks of his criminal occupation than she finds in her repose in Labardi’s well-appointed household, with the servants and decorum all keeping Maddalena in check at every turn. Likewise, Calvert herself seems to be having a good time smirking and smoking in her low-cut gypsy blouse and trading snappy wisecracks with the riff-raff. Almost too good a time, as a matter of fact… so you know what’s coming: the moralistic conclusion in which all these bad deeds are deservedly punished.

Yes, I’m skipping over all sorts of plot mechanics and role reversals that unspool over the last half of the film. Angela (played by the cutey Patricia Roc, same age as Calvert despite them being cast as daughter and mother) becomes more sensible, less impulsive as the seriousness of her mother’s mysterious disappearance sinks in. There are various bits of mystery-solving and clue-gathering that go on in order to bring together Labardi’s assistants, Angela’s traveling companions and Nino’s street gang as the narrative tension builds. There’s even some festive street pageantry and romantic musical interludes to round out the movie’s sheer entertainment value. But the most evocative and emotionally gripping scenes occur toward the end, as the disparate elements of Maddalena/Rosanna’s tormented psyche manage to reconnect before the film’s tragic conclusion. The parallels between pagan revelry and Christian ritual are brought into clear cinematic juxtaposition, lending at least a symbolic veneer of resolution to this feminine twist on the Jekyll and Hyde archetype. Madonna of the Seven Moons‘ finale in a burst of Catholic iconography places it rightfully alongside Rafaello Matarazzo’s Runaway Melodramas, despite the gaps of language and time between them.

![Bergman Island (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/bergman-island-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/this-is-not-a-burial-its-a-resurrection-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![Lars von Trier's Europe Trilogy (The Criterion Collection) [The Element of Crime/Epidemic/Europa] [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/lars-von-triers-europe-trilogy-the-criterion-collection-the-element-of-400x496.jpg)

![Imitation of Life (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/imitation-of-life-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (The Criterion Collection) [4K UHD]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/the-adventures-of-baron-munchausen-the-criterion-collection-4k-uhd-400x496.jpg)

![Cooley High [Criterion Collection] [Blu-ray] [1975]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/cooley-high-criterion-collection-blu-ray-1975-400x496.jpg)