After spending the better part of February taking a break from my multi-year pilgrimage through the Criterion Collection (but continuing to movie-blog on this site, reviewing a few DVD releases and five titles from the 2013 Portland International Film Festival), I took an early-March vacation out Oregon way (where I enjoyed an epic exchange of OOP Blu-rays with none other than Ryan Gallagher himself and visited the lodge where Stanley Kubrick filmed exteriors for The Shining.) After all that diversion, as wonderful as it was, I knew I had to take some time refocusing my attention on my Criterion Reflections blog, which had lain dormant since mid-January. I even went so far as to tell Ryan that my Journey Through the Eclipse Series would go on hiatus for awhile so that I could dedicate my efforts elsewhere. But then along came Akira Kurosawa’s 1963 masterpiece High and Low into my queue… and after watching it, I realized that, before I could adequately review that crucial work from the tail end of his golden age in Japan, before the laborious production of Red Beard marked a culmination of that phase of his career, I needed to return to his earliest phases, simply to recognize just how far he had progressed in his own journey into cinema. So I’ve chosen to review The Most Beautiful, AK’s second film and one that, like High and Low, also deals with industrial production, but from a radically different perspective, roughly twenty years earlier in Japanese history, just as the tide of the Pacific War (WWII) was beginning to turn against the Rising Sun’s imperialist ambitions.

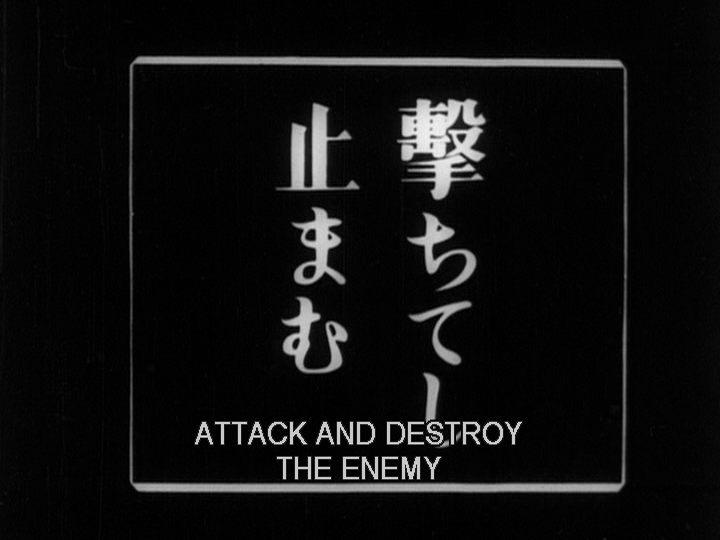

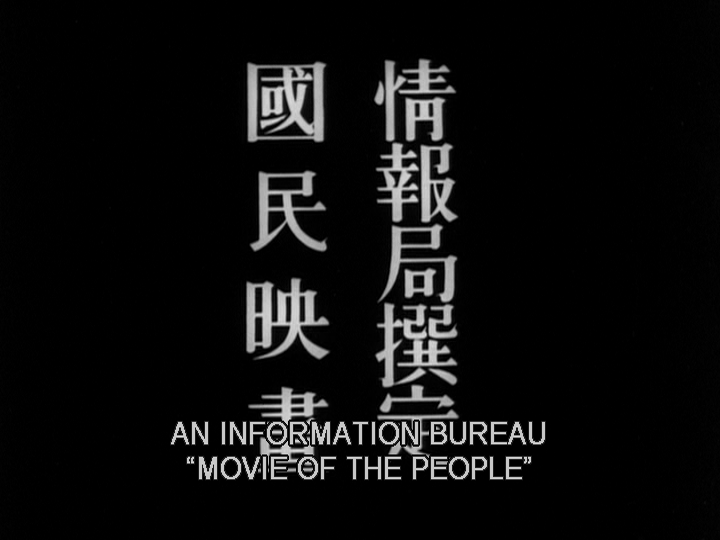

One of the most remarkable details about The Most Beautiful (part of Eclipse Series 23: The First Films of Akira Kurosawa) is that you won’t find any mention of Kurosawa in the credits – indeed, there are no credits at all to speak of. The film, released in 1944, opens with a stern admonition: ATTACK AND DESTROY THE ENEMY. Other than the Toho Studio logo, the only other text seen on-screen before the title (and there are no end credits either) is the acknowledgement thatThe Most Beautiful is brought to us by the “Information Bureau,” presenting a “movie of the people.” It’s an easy statement to overlook, but it’s as indicative as any introduction could be as to the film’s emphasis on providing a form of government sanctioned propaganda, aimed at steering the emotions of its viewers in service of a cause that those who were in the know at that time almost certainly realized was utterly doomed. Indeed, Japan’s surrender was merely a little over a year away, but the territories conquered in the late 1930s and early 40s were already being overrun by Allied troops, even as Kurosawa and his colleagues in the Japanese film industry continued to exhort their fellow citizens to work harder, to sacrifice more, to intensify their resolve, despite whatever adversities they may soon face.

This blatantly manipulative subtext makes watching The Most Beautiful somewhat of a struggle on multiple levels. For starters, the story is rather plain and simplistic. A group of young women (teenagers, really – it’s more accurate to simply call them “girls”) work at an optics factory, making lenses that are used in long range artillery and aircraft weapons. As the military and economic conditions grow more dire, the laborers are pressed to meet increased production quotas: men must double their output, women must add at least half of what had been expected of them. The girls press on through fatigue, illness, family crises, etc. and find encouragement in their difficult circumstances. That’s pretty much all that happens, without going into further detail.

Beyond that prosaic and futile premise, there’s the sad realization that even a great humanist and genius like Akira Kurosawa could be persuaded to craft a defense of what is essentially forced child slave labor on behalf of an oppressive totalitarian regime. (And yes, he did write the screenplay himself, he wasn’t just a hired hand crafting shots from behind the camera.) In his defense, he was young, and of course the Empire had enormous powers of persuasion, let’s just say, even outside of understandable pride and dedication that people in every nation will take when they find their country hard-pressed by a strong and fearsome adversary. But it’s hard (at least for me) to shake off that sense of dread, seeing all these young people following their orders so obediently, so blindly. And I can’t help but wonder just how many of them perished or suffered terribly, for what purpose, in the numerous bombing raids that finally led to the war’s end in the summer of 1945.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4aGLVlywGp0?rel=0]

This video clip (lacking English subs) gives at least a sample of the film, a highly condensed version of its narrative arc, conveying in vocal tone and imagery the submissive martial spirit of The Most Beautiful. That is indeed Takashi Shimura in the first sequence as the factory chief Ishida barking out his decrees to the assembled workers, standing rigidly at attention. He doesn’t do much else in the role, giving very little indication (other than perhaps a commanding voice) of the awesome sublime heights he would achieve over the next 15 years or so. The rest of the clip focuses on the camaraderie of the girls as they encourage and challenge each other through various group activities – marching, singing, making music, reciting oaths. Obviously, they are meant to serve as role models for their audience, some of whom at least couldn’t be faulted for lacking the same patriotic fervor we see captured on film. But I have little doubt that Kurosawa was also reflecting some of the admirable dedication and perseverance that he saw around him at that time. Though it may require a bit of empathic stretching for some viewers to set aside the fact that these workers were serving a cause that made them mortal enemies of older relatives and fellow citizens, getting over that hurdle is worthwhile, if for no other reason that it helps us to avoid getting caught up in future war hysteria (and I write this just as the USA observes the tenth anniversary of our own calamitous launch of a horrible war against the people of Iraq.)

Beyond the sorrow instilled by thinking of how the women’s labors were squandered and the dryness of the plot (especially when compared to so many other utterly thrilling stories that Kurosawa went on the produce), The Most Beautiful does offer some occasional hints and indications of AK’s growing skills and confidence as a director. We see him beginning to master both the compositional techniques of large crowd scenes (though they hardly qualify as “action sequences” – an intramural volleyball game is about as rambunctious as it gets) and emotive close-ups, cut into montage passages that show the girls at work and actually do provide an interesting documentary of industrial processes of that era – if you’re into that sort of thing.

Kurosawa also weaves in some moments of light natural mysticism and fondly recalled childhood memories, accented with a gentle humor that occasionally throws an interesting dash into the generally somber tone of the film. The outdoor scenes are a welcome relief from the production’s heavy reliance on drab factory and dormitory interiors, but never approach the intensity of the two part Sanshiro Sugata saga that Kurosawa filmed as bookends to The Most Beautiful.

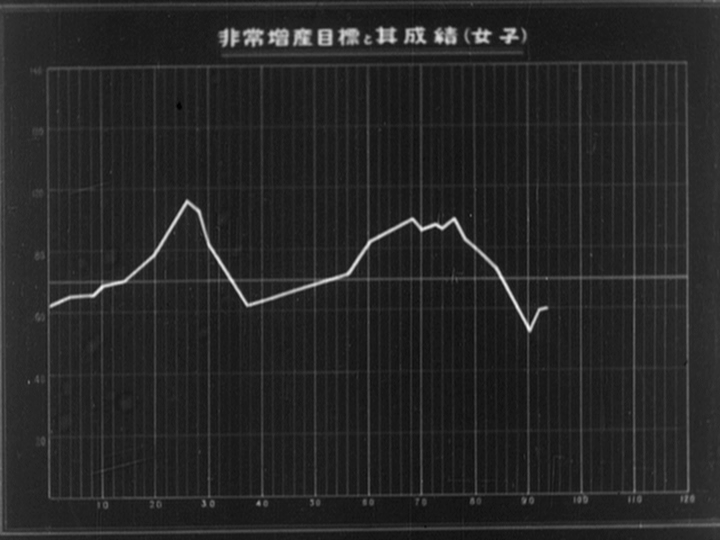

Still, the overwhelming impression left by The Most Beautiful is its overt attempt to provoke feelings of motivation and inspiration to its audience, as distant as we may be from it in time, culture and (for most of us anyway) geography. There are also some rather clunky attempts to build suspense and anticipation in the viewer by graphics depicting the workers’ production rates, with the arrow dipping down when times get tough, but “optimistically” trending upward as health is restored and other dilemmas are resolved. Sorry, but collective efforts to feed the war machine just don’t get me pumping my fists that way… Despite those differences between my perspective and that of the film, I am able to find something to admire in its depiction of female solidarity in hard, depressing circumstances.

The other aspect of The Most Beautiful that distinguishes it from just about every other film in Kurosawa’s canon is its emphasis on female characters. The only other one of his movies that comes close is No Regrets For Our Youth, shot just two years later, starring the wonderful Setsuko Hara (known mostly for her work with Ozu) as its main protagonist. Indeed, the two films would make for an intriguing double bill, a before-and-after snapshot of Kurosawa’s conflicting perspectives on the war’s impact and meaning. As the director went on to hit his full artistic stride, he better recognized his strengths and went on to create some of the most memorable and influential male archetypes in all of cinema, leaving the depiction of female characters to more capable hands. Some would see that as a weakness or oversight on Kurosawa’s part, and I won’t argue with such a verdict. Even the women in this film, including the self-sacrificial Watanabe, pictured weeping above (and portrayed by his future wife Yoko Yaguchi) are mostly one-stroke characters, more idealizations than complex, whole personalities. Even with such rudimentary portrayal, their spirit, what makes them truly The Most Beautiful, is the dignity of their service and the purity of their commitment, even when they’re not shown the degree of respect and compassion that such nobility clearly deserves.