It’s a poor thing, to command in love.

Have you ever been to a Renaissance Faire? I’ve been to a few over the years, though I’m far from being a regular attender. The last Ren Faire I visited was when I took my family to one here in Michigan sometime in the early 2000s when The Lord of The Rings was at the zenith of its pop-culture ascendancy and my kids were into stuff like swords and magic and capes and gowns.

I figure most readers would know what I’m talking about, but for those who don’t… Ren Faires are public events where people who are into that sort of thing are employed or pay admission to dress up in the garb of various types of medieval personae, spending a day, a weekend or longer getting into the roles and habits of Europeans who lived around 500 years ago or so. The festivities typically take place in the autumn of the year, when brisk temperatures make it more tolerable to adorn oneself in heavy layers of fabric that are often required to pull off a reasonable facsimile of the characters of that era.

Among the choices participants have for their annual rounds of Middle Ages make-believe, we can choose to be a knight or a wizard, a princess or a peasant, a minstrel or a wench, any and all varieties of rogues and ruffians, or just a plain-clothes spectator, if we’re not ready to go all in and commit to the full role play. Regardless of the depth of our commitment, there’s usually plenty to observe and enjoy. I appreciate the chance to gnaw on a giant turkey leg and wash it down with a tumbler of ale in a rustic setting. And I can always count on seeing at least one man who struts around bearing an uncanny resemblance to this guy:

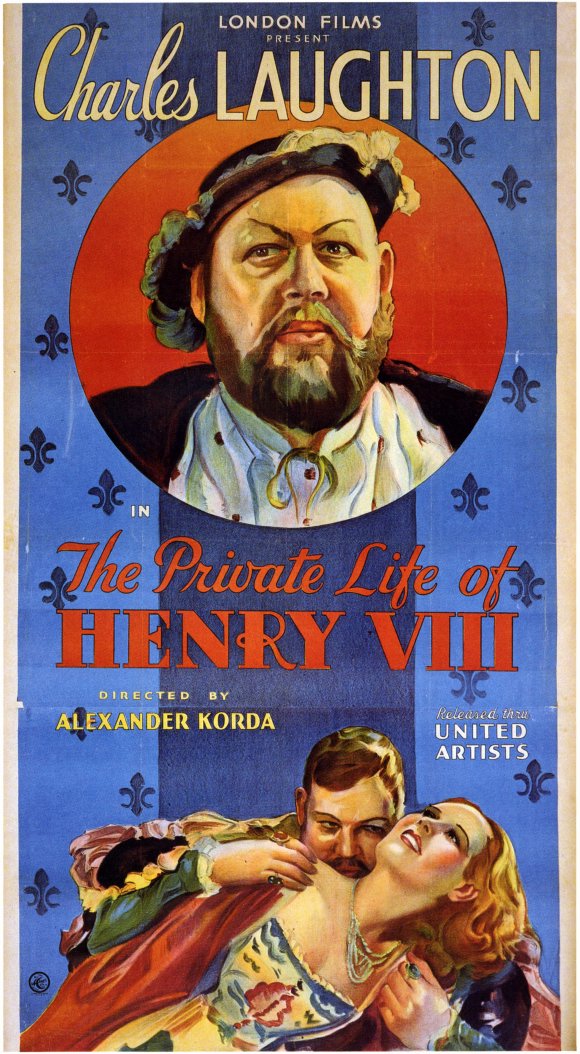

Though I haven’t been to a Ren Faire in a few years and don’t plan on making my way to one any time soon, the season and its remembrance serves as good enough an excuse to watch Charles Laughton establish the role as his personal domain in The Private Life of Henry VIII, part of Eclipse Series 16: Alexander Korda’s Private Lives.

This film, and the other early works of Alexander Korda featured in this set, are important today because they helped establish a very significant imprint among British movie production companies, London Films, readily identifiable by the Big Ben logo that opens such illustrious titles as The Thief of Bagdad, The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, A Canterbury Tale, I Know Where I’m Going!, The Fallen Idol, The Third Man,The Tales of Hoffmann, and Summertime (among many others.) Without the early success of The Private Life of Henry VIII, who knows how Korda’s career would have progressed, or how the cinematic arts might have suffered if he was not around to produce would so many triumphant classics?

The “Private Lives” films also happen to be quite amusing in their own right, though anyone approaching them for the first time should keep in mind their age and the limitations of where a story could go in that era. With a generous but not excessive allowance for the scruples of nearly seven decades previous to our own, The Private Life of Henry VIII serves up a platter full of bawdy entertainment to anyone interested in stories of the British monarchy or the early career of a particularly gifted and troubled actor.

I refer to Charles Laughton, of course, whose Oscar-winning ability to fully inhabit and project the character of Henry VIII to modern audiences remains unparalleled to this day. Laughton went on to perform in many memorable roles, making his first entry into the Criterion Collection via David Lean’s adaptation of Hobson’s Choice, though he’ll soon be featured in his only directorial effort when Criterion releases Night of the Hunter later this year.

Henry VIII stands alongside such Shakespearean portrayals of earlier English kings like Henry V and Richard III as larger-than-life archetypes, epitomizing outsized personality traits that even those who are unfamiliar with the history of the English kings can readily identify. Just as Henry V has been distilled, through Shakespeare’s play, as a bold and courageous leader, and Richard III as the very essence of a relentlessly cruel and despicably charismatic manipulator, Henry VIII stands out as the champion of wanton lustiness, possessor of a gluttonous appetite for food and drink and an insatiable desire for “the other woman.”

Renowned for his six marriages, most of which ended in tragic circumstances, the character of Henry VIII had already been established in the public consciousness to a certain extent by the time The Private Life of Henry VIII debuted in 1933. But from that time forward, I think it’s fair to say that this film has served as the primary reference point for Henry VIII’s modern reputation in popular Western culture.

This passage below offers a pretty generous slice of Laughton’s performance as his rendition of Henry VIII holds court at a royal banquet. I’d never seen this film before, yet just one look at him in the role establishes it as authoritative. At this point in the story, Henry has already dispatched of his first wife through divorce, his second (Ann Boleyn) through execution, and lost his third (Jane Seymour) through a traumatic childbirth. Now, even though he’d already produced one male heir to the throne, he’s feeling pressure from his advisors to marry again, in the hopes that he’ll provide more offspring and add security to his line of succession to the throne.

The young woman he asks to sing for him, Katherine Howard, is destined to be Wife #5, which implies, of course, that Wife #4 still has to be wooed, wed and disposed of before she can take her turn. You’ll meet her a few minutes in, arguing for her exemption from this fate while standing in a field of sunflowers. That woman, Ann of Cleves, is played by Laughton’s real-life wife, Elsa Lanchester, in a playfully comic bit that probably plays fast and loose with history but makes for better entertainment.

Beyond the matrimonial and courtly intrigues, there are some nice cinematic effects – the tracking shots of privileged attendants devouring their meals, followed by the uproarious sycophantic laughter of aristocrats and servants alike as they all seek to placate the notoriously moody and petulant king:

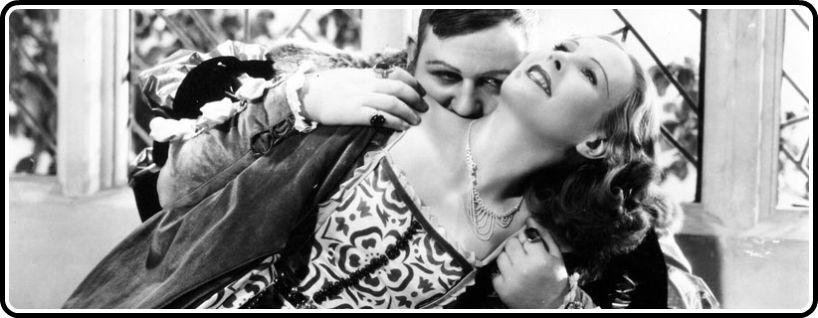

Laughton does a terrific job strutting about his palace, conducting himself as I suspect many of us would if we recognized and embraced the privileged status of being a king that nobody had a realistic opportunity to say “no” to: gorging himself on the finest cuts of meat and bottomless draughts of ale, leering shamelessly at attractive women, doubling the size of his navy without considering the expense, blustering and fuming without remorse, however his mood moves him.

Henry has the opportunity to pursue whatever cravings he feels like satisfying, and wastes little time pushing those limits, at least until he encounters women just as shrewd and strong-willed in their own way as he is. Though they pale in comparison to Laughton’s star-making role, a couple of supporting actors are worth mentioning here. The beautiful Merle Oberon (very young here, and the future Mrs. Korda, for a few years) takes center stage for a few minutes at the beginning of the film as the doomed Ann Boleyn, and we also get to see Claude Allister briefly as dithering servant – he was the dimwit Count Rudolph from Lubitsch’s Monte Carlo.

As a story, it’s the high-stakes battle of the sexes, played out on an opulent stage, that gives The Private Life of Henry VIII a degree of relevance beyond historic value and mere admiration for Laughton’s craft. As the king goes through his succession of spouses, he comes across as more of an overgrown child than a serious man matured and tempered through life experience. It’s not until his appetites have been satisfied and the desires behind them have been thoroughly thwarted through deception and heartbreak that he finally emerges, toward the end of his life and this film, as a broken and bereft man, yet able to find contentment in what life offers him rather than what he wishes it might be. By then, of course, he’s a decrepit, enfeebled old codger. But before he takes leave of us, he shares a bit of hard-earned wisdom: “Six wives, and the best of them’s the worst!”

1 comment