“A two-hour wait? . . . Yes, I’ll wait.”

The words are spoken in a phone call to hotel room service by the titular character in Chantal Akerman’s Les Rendez-vous d’Anna just ten minutes into the film. Whether she intended it as a self-aware joking acknowledgement to her audience or not, the expression aptly fits what we’re in for at that point in the movie: two more hours of waiting around through Akerman’s trademark long, fixed and sonically ambient shots, quietly watching with a muted blend of dreadful alienation and detached curiosity, anticipating whatever it is that will happen next.

Last Thursday, March 8, marked the annual observance of International Women’s Day, and a pleasing confluence of timing and happenstance gave me the opportunity to post my latest Criterion Reflections review of Jean-Luc Godard’s A Woman is a Woman that very evening. So for this weekend’s follow-up to that early 60s look at femininity from a particularly lovestruck male auteur’s perspective, I chose a title created nineteen years later by a female director whose destiny was forever changed as a teenager when she saw Godard’s Pierrot le fou and decided that she too wanted to become a filmmaker. Les Rendez-vous d’Anna is the last film I have yet to review for this column from Eclipse Series 19: Chantal Akerman in the Seventies. But before I could do that, I had to wait just a few hours more so that I squeeze in a viewing of Akerman’s definitive masterpiece, Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles. Having followed her career in chronological order up to that point (for the most part,) I figured it was important for me to get familiar with Jeanne Dielman so that I could better appreciate what Akerman did as a follow-up to the movie that made her the talk of the mid-70s art house scene.

Jeanne Dielman had several distinctions that helped the film break out of the narrow avant-garde circles that first came to appreciate Akerman’s work. It starred the beautiful and adventurous Delphine Seyrig, whose résumé of directorial collaborations – Bunuel, Truffaut, Duras, Zinneman, Resnais, Klein – is about as impressive to me as any actor of her generation. (See my reviews of Last Year at Marienbad and Mr. Freedom as examples.) Seyrig convincingly takes on the persona of a highly repressed, obsessively methodical housewife and widow who relies on precisely timed appointments as a prostitute, receiving clients in her home for the income that helps make ends meet. Jeanne Dielman‘s massive 3 1/2 hour running time, with most scenes set in her mundane bourgeois household or the drab streets around her apartment, raises a daunting challenge to the casual movie-goer, but more than compensates for the necessary adjustment by drawing viewers into its fascinating web of order and repetition through sheer force of will, until our sensibilities become attuned to notice the small, subtle changes to the routine that ultimately have such a devastating effect on Madame Dielman and others. Informed and fluent in the feminist discourse and sexual politics of her era, Akerman assembled an almost entirely female production crew just to show that it could be done in an industry so eager to demonstrate its enlightened awareness of cultural matters on the one hand, yet so traditionally male-dominated that the imbalance of power was hardly noticed and regularly taken for granted on the other.

With all that momentum behind her, and widespread acclaim from critics and other taste-makers whose opinions mattered in that subculture, anticipation ran high as to what Akerman would do next. When the follow-up was released, she experienced some backlash for setting aside her principled reliance on women as crew members and taking a more conventional approach to the production details. But she can hardly be accused of “going commercial” or “selling out.” Les Rendez-vous d’Anna seems today in retrospect a very worthy successor, continuing Akerman’s exploration and articulation of the feminine experience in a generation younger than Dielman‘s housewife approaching middle age, though in a film more concise and less overtly demanding due to a greater variety of interpersonal situations. Some reviewers have even recommended it as the preferred entry point to this early period of Akerman’s career, though I think it’s better to just buckle down, work through the challenges of Hotel Monterey, La Chambre and News from Home (aka her “New York Films”) and Je tu il elle, and then regard how her themes in those films come to fruition in Les Rendez-vous d’Anna.

The opening scene, in the clip embedded above, sets the slightly ominous tone and fairly shouts “THIS IS AN AKERMAN FILM,” to the trained eye, anyway. Though we know nothing of what’s going on beyond the plain fact that we’re in a mass transit station, the symmetrical lines of the train platform converging toward a distant centerpoint, the calm, meditative pacing and the unblinking tranquility of the shot create a sense of staring into urban oblivion. The clopping of shoes on concrete precedes the migration of a small crowd into our view as they wordlessly descend the stairs en route to their respective destinations… except for that one woman, set apart by her own volition, stepping outside of the flow of bodies in order to make a phone call yet too remote for us to eavesdrop on the conversation. Most directors would have cut in for a close-up or at least made us privy to whatever the woman is saying on the phone, but we’re suspended, held off at a distance. Priority is given instead to the sound of a whistle and the train pulling away. Even after she leaves the phone booth and trails behind the other disembarking passengers, the scene doesn’t conclude until well after she’s off the screen and the other incoming train has passed entirely through the frame. It’s just an initial salvo, nothing too extraordinary by itself, but already the weightiness is beginning to accumulate as we join Anna on the series of meetings that comprise the narrative.

Arriving at her hotel in Cologne, Germany, we see that Anna is an attractive and forthright woman, in her late 20s, enough of an eye catcher to draw and hold the attention of the gentleman idling away a few moments in the lobby – before she notes his gaze and wordlessly nudges him to turn away. Like Akerman, Anna is a female film director with the responsibility of traveling from city to city to talk business, make public appearances and promote her work. Though no background context is provided to explain why, she apparently travels alone most of the time, too much the struggling artist to afford her own entourage, effectively deglamorizing any notions the audience may have about the fascinating fun times that fill up the days and nights of a career spent in showbiz.

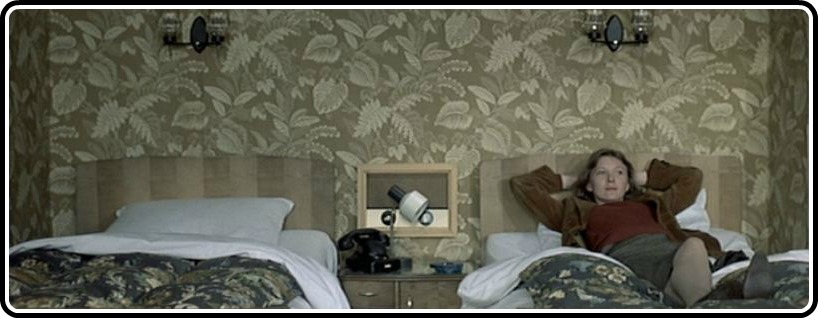

Alone in her hotel room, with a few hours to kill before heading to her assignment that evening, Anna looks out her window, examines the shelves and closets, finds a man’s tie that’s been left behind. She reports the lost tie to the front desk, concerned that it be returned to its rightful owner… perhaps that man who was checking her out when she first arrived. Why does Akerman include such minute trivialities in a two-hour film? If she’d edited it out, no one would have missed it. (And the tie does not play any part in what follows, just to be clear.) Anna is Akerman’s stand-in here, employing the same disciplines that her creator uses not just in making her films but in how she goes about life: always observing, continually scrutinizing each object and view, honing her perception to catch every significant detail, drilling down into the meaning and value of what she sees.

As Anna moves through her first rendez-vous, a late night pick-up with Heinrich, a handsome blond local whom she takes back to her hotel room for a sexual encounter, Akerman guides us through passages that would be skipped over in most tellings of this tale – the silent walks down quiet illuminated streets, the entry to the hotel through sliding electronic doors – while skipping over the parts that ordinarily interest us the most – the flirtations, the banter, the charming acts of seduction that precede the intimacies. Then, having skipped straight into the bedroom scene, she again thwarts expectations by bringing it all to a screeching halt as Anna’s dissatisfaction with the situation prevents her from yielding to the seemingly inevitable.

To his credit, Heinrich doesn’t force things any further. In fact, he comes across as a thoroughly decent and admirable man, the kind of guy who would treat Anna with respect and provide a stable and caring partner for her to whatever extent she could allow a relationship to develop between them. But she doesn’t, she can’t – not because of any fault in this kind-hearted but naive and achingly lonely man (who will almost certainly find himself a woman soon enough) but because Anna is pursuing something else, she knows not what exactly, but the pursuit refuses to let her settle down into the domestic cul-de-sac that would undoubtedly stifle her artistic aspirations.

Similar disconnects conclude each of Anna’s subsequent meetings as she continues her impromptu tour of Europe. She receives news from home – her mother, her current male companion Daniel, each requesting to see her soon if she can fit some time in. She eventually meets up with each of them, but only the exchange with her mother can be regarded as anything resembling satisfactory. Random encounters also disrupt the ever-present risk of lapse into ennui that seems to hover over Anna in her less preoccupied moments. She crosses paths with Ida, the mother of a man she was once engaged to, and has to endure guilt-ridden pleas from the woman to resume a relationship that Anna walked out on without any explanation.

Later, after wriggling loose into a bit of free space from a claustrophobia-inducing passenger railroad car, she shares a smoke with Hans, a fellow traveler who, like Anna, has traveled the world so continuously that he now considers himself a rootless wanderer, though he’s ready to give France, where Anna now lives, a chance to live up to its reputation as “the land of freedom.” Experienced, handsome, intellectual, witty, independent, a German who speaks French very well… is Hans the kindred spirit that Anna could connect with? He seemed willing enough to explore, if she’d only give him half a chance. But that’s asking too much.

The clip above shows the moment where Anna lets down her guard more than at any other time in the film, either to another person or even to herself. As she confesses to her mother (with who she’s sharing the bed, after meeting in a hotel late in the evening) that she had a recent and unexpected lesbian encounter, Anna is still weighing her words carefully, but without the palpable aura of apprehension that filters all her other interactions. The exquisite moment of vulnerability proves to be a bit more than either of them are comfortable sustaining though, so the conversation quickly reverts to small talk and memories from Anna’s childhood.

The clip below occurs near the end of Les Rendez-vous d’Anna, when she uncharacteristically breaks into song at the request of her boyfriend Daniel, who’s happy to see her but not feeling well and needs something extra from her to get him in the mood for love. He asks her to sing him a song, and so she offers him this, a mournful little ditty that offers some piercing insight on Anna’s/Akerman’s views on love but seems sadly lacking in aphrodisiac effect. (Lyrics transcribed below)

I wash the dishes, fix coffee with cream

I’m so busy, have no time to dream

I work all day in this cheap little place

Flowers on the table, curtains of lace

Young lovers come here holding hands

Wide-eyed, hopeful, they make no demands

They bring in the sun, my life they enchant

A bed built for two is all they want

I can’t forget how happy they seem

Joy on their faces, smiles that beam

When I think of them there in that sad little room

It chases away my workaday gloom

Faces that shine like rays of the sun

So bright that it hurts

So bright that it hurts

I wash the dishes, fix coffee with cream

I’m so busy, have no time to dream

I work all day in this cheap little place

That’s where they found them, face to face

Lying together, still holding hands

Dreaming of oceans and golden sands

They were buried in the city, side by side

Even the earth, their joy could not hide

When I think of them in that sad little room

It chases away my workaday gloom

Lovers for a day, faces that shine

Like rays of the sun, like rays of the sun

A little sunshine can shine so bright

So bright that it hurts

So bright that it hurts

Just by way of comparison, you may find it amusing like I did to juxtapose Anna’s song and context, after 15 years of progress on the Women’s Liberation front, with the striptease jingle sung by Angela/Anna Karina in Godard’s A Woman is a Woman (that video is posted on my Criterion Reflections review, though I used the Spanish subtitled version because it has the correct aspect ratio; English subtitles are available on YouTube if you prefer.)

After Anna’s rendez-vous with Daniel falls to pieces, she’s left to reckon with the depths of her loneliness. Even though her breakdown isn’t quite as intense as the one experienced by Jeanne Dielman, they register similarly with us as we’ve seen each of the characters slowly build toward their respective moments of crisis. The big difference is that, even though we don’t know exactly what will become of Mme. Dielman, we’re still sure that her world as she knew it has come to its end. With Anna, it’s a safe assumption that she will continue to forge ahead, pushing the solitude and alienation aside simply because she’s so deeply committed to her project that turning away from it is not even an option. She has no other choice but to come to grips with what’s lacking and address her unmet needs the best she can, while continuing her work.

There’s one other thought I have here that I’ve been kicking around but haven’t taken the time to fully develop, and that’s the connection between film makers like Godard and Akerman and a new young female director like Lena Dunham. The thesis goes something like this: Godard started his cinematic career in the then-peaking creative milieu of 1950s Paris and only traveled to New York in the late 60s after his craft and reputation were secured in Europe. Chantal Akerman was born in Europe but, as the European cinema scene was in relative decline, for newcomers anyway, she had to travel to New York to finish accumulating the formative influences that shaped her work, after which she returned to Europe and has been primarily working there ever since. Lena Dunham was born and raised in New York, left the city briefly (for college) but has since come back to Manhattan and has now parlayed that advantage to get her own career in film started via Tiny Furniture and her soon-to-debut series on HBO, Girls. Though my assertion may seem like baseless provocation or mere silliness to some readers (I’ll grant you that), I can see some artistic continuities between Akerman and the widely reviled Dunham in how they both incorporate their life experiences quite deeply into their earliest films, and their willingness to expose themselves on-screen in boldly unflattering ways. They both possess a distinctive voice that expresses important things to consider about what’s happening with young women in their respective worlds. Where Dunham takes her talent from here is yet to be determined, though. It wouldn’t be fair to impose upon her some burden of expectations to be as innovative and relentlessly non-commercial as Chantal Akerman, one of the most distinctive auteurs of the past forty years. And of course, Lena Dunham hates foreign films, so she says. Like I said, this is still a half-baked notion on my part. If anyone wants to take up the discussion in the comments section, I’m game, let me hear from you.