After spending the past five weeks in this column on Eclipse Series 32: Pearls of the Czech New Wave, I’m feeling eager to move on to other things – in particular, the new Jean Gremillon set. But I’m going to finish what I started next week with the sixth film from the Czech Box, Jaromil Jares’ The Joke. And as it turns out, I’m really glad to have spent time this weekend watching Capricious Summer, director Jiri Menzel’s follow-up to his Oscar-winning Closely Watched Trains. It’s a wonderful little diversion that, like most of the films in this collection, may require a bit of settling in and rewatching to fully appreciate, since its witty observations and wry humor are of the subtle sort that doesn’t make its full impact until you build a little familiarity with the players and their predicaments. Clocking in at a mere hour and fifteen minutes, these are guests you won’t mind inviting over for a return visit.

As was the case with the omnibus Pearls of the Deep, Capricious Summer draws from a Czech literary source, swapping Pearls‘ contemporary adaptation of Bohumil Hrabel short stories for a novel written in 1925 by Vladislav Vancura, who was popular with Czech readers in the years prior to World War II and traveled in the same social circles as Franz Kafka. Vancura is regarded as one of the most important Bohemian writers of the 20th Century, with an inspiring body of work and life story – he took up arms against the Nazis after Czechoslovakia fell in 1939 and was executed by SS troops after being captured and tortured by the Gestapo a few years later. Menzel would return to adapting more of Vancura’s writings with another comedy, The End of Old Times in 1989.

Presumably oblivious to the dark turn that his nation’s history would take in subsequent decades, Vancura (and in turn, Menzel) sets Capricious Summer‘s story in a sleepy, heavily wooded riverside village somewhere in the Czech countryside in the early years of the 20th century. Three old friends have gotten together on a balmy June afternoon to enjoy a few drinks, wax philosophic and frolic around in the water. But an ill-timed turn of the weather brings the promise of a fun summertime reverie to a premature and unsatisfying conclusion.

Antonin, the stubborn and unabashedly carnal minded proprietor of the no-frills bath house that hosts their get together, is pictured above, contemplatively clutching the saturated stub of his stogie. For him, the bad weather isn’t just a cause of disappointment, it’s also a financial liability since business will be slow. More than that, the dismal overcast seems to be delivering an unwelcome hint at his own sagging vitality and diminished prospects as the slow, inevitable crawl toward old age and irrelevance becomes more difficult to resist, and impossible to postpone.

His two companions, unlike their friend the plain-speaking working man, each have official titles and roles to help cloak their underlying insecurity as they too settle into life’s great decline. Hugo, a military officer, carries himself in an attitude of fairly rigid pomp and authority, though it’s not too difficult to see through the cracks in his psychological armor. At this point in his career, he’s just a lifer in the upper ranks, but not destined for much of lasting importance, content to coast on past glories and knowing his weapons will probably remain sheathed for the remainder of his days.

Roch is a clergyman, referred to as a canon in the subtitles, something along the lines of a priest, from what I gather. A man who’s lived a celibate life, dedicating his energies to a peaceful, mild religious vocation, who yet seems to get some enjoyment from keeping company with these two men hewn from rougher cloth – if for no other reason than finding frequent cause to upbraid them for their lack of attention to the Scriptures and for being too easily swayed by the latest intellectual fads and whims of their reckless bodily impulses.

Of the three, Antonin is the only one with a spouse, the chronically bored and once-upon-a-time competitively coveted Katerina. We learn that Antonin’s brute determination to win her hand (if not entirely her heart) resulted in her finally succumbing to his overtures, once he’d intimidated the competition into giving up the pursuit. After a couple decades of marriage (but no kids?), she and Antonin have settled into a persistent, low intensity grudge match of sniping and wrestling for the last word in their ongoing series of petty disagreements. His lack of ambition, the bath house’s meager profit margins and the general aimlessness of the life they’ve created for themselves have them both stuck in a rut.

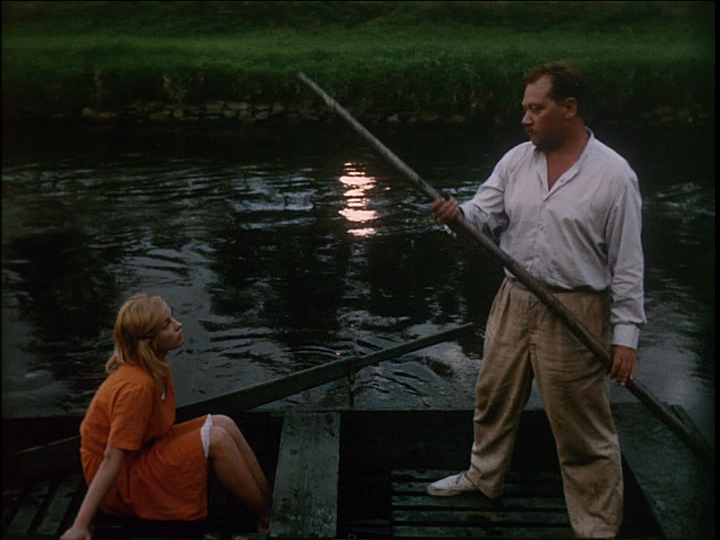

But the inertia is broken by the unexpected arrival of a traveling acrobat and magician named Ernie, who makes a brash “walking on water” entrance that grabs everyone’s attention. Using his adept physical, verbal and sleight-of-hand skills, Ernie informs Antonin and his friends that he’ll soon be performing shows in the town square – and manages to cajole a free lunch out of them before they realize that he never paid the price of admission.

Ernie’s promise of a sideshow spectacle is enough of a change from the usual routine to stir the men’s curiosity that evening. Approaching the carnival scene, they spy clandestine groups of young lovers embracing each other in the bushes, ruefully acknowledging that such pleasures are no longer available to them. As Antonin puts it, “There are painfully few pretty girls, but they exist. Each of them has her own tool, and they are all present here.” Sigh. But even that hard-earned worldly wisdom is no match for the flood of basic instincts that erupt when Ernie’s gorgeous assistant Anna steps out of their gypsy wagon. Her shapely frame and flawless features galvanize their attention. Suddenly, their summer’s night meandering has a purpose!

But before we turn our attention to the three men and their successive (though not very successful) pursuits of Anna, it needs to be said that Katerina also gets her turn to play. Ernie’s unique talents and unusual expression of virility works its own brand of magic on the jaded homemaker, who’s more than happy to throw a copper in the plate for the pleasure of watching her favorite new entertainer strut his stuff.

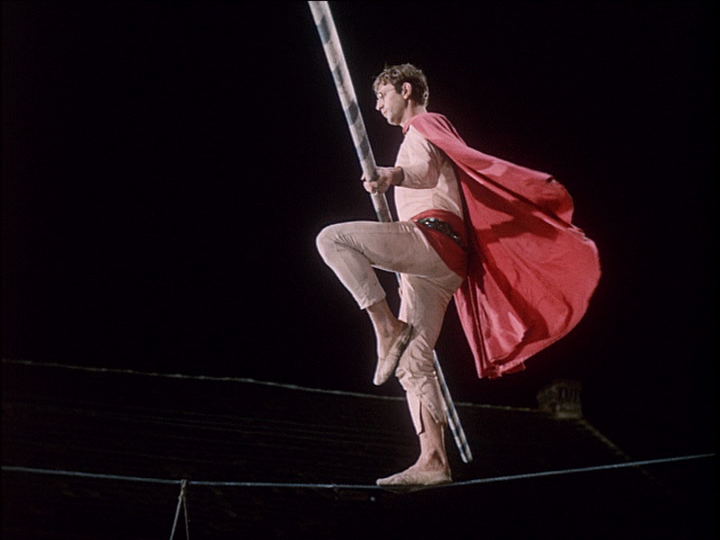

While the high-wire act and stage magic are not what seasoned circus fans might consider representative of the highest caliber, what’s truly impressive is the fact that the film’s director, Jiri Menzel, is the guy doing the stunts. Menzel apparently took lessons in order to learn how to keep his balance on the tightrope, and he does a great job at that, putting his body on the line in several scenes, going well beyond the usual call of a director’s duty in bringing his film to life.

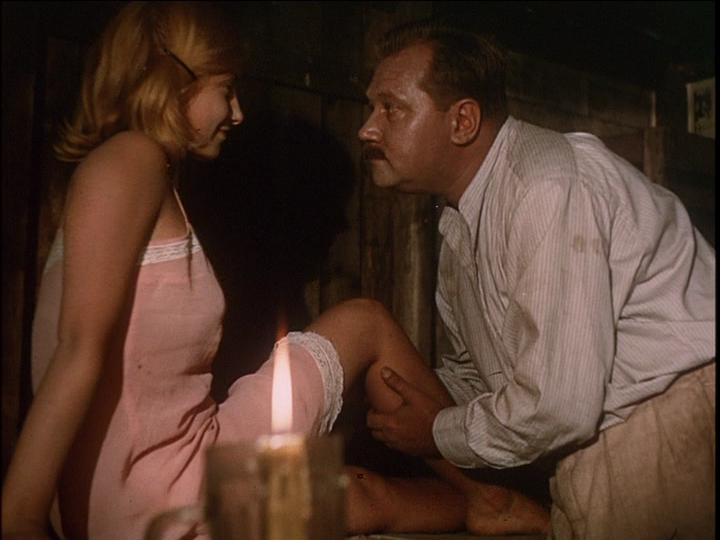

With the basic plot set-up thus spelled out, all that remains is to see our protagonists persist in their folly as they each take a crack at seducing Anna and reclaiming, at least for a night, a portion of the vigor they once so easily enjoyed in their bygone youth. Antonin, the most characteristically brash of the three, gets first dibs of course. He aggressively pursues Anna that same night, and seems en route to some amorous success with the pretty young woman, until he swiftly realizes that he’s just not quite up to the task. An affectionate, paternalistic foot rub has to suffice, until he’s caught in the act by his angry wife and must quickly improvise drastic measures to concoct a persuasive reason for being alone in his workshop in the wee hours of the morning with a woman wearing only a nightgown.

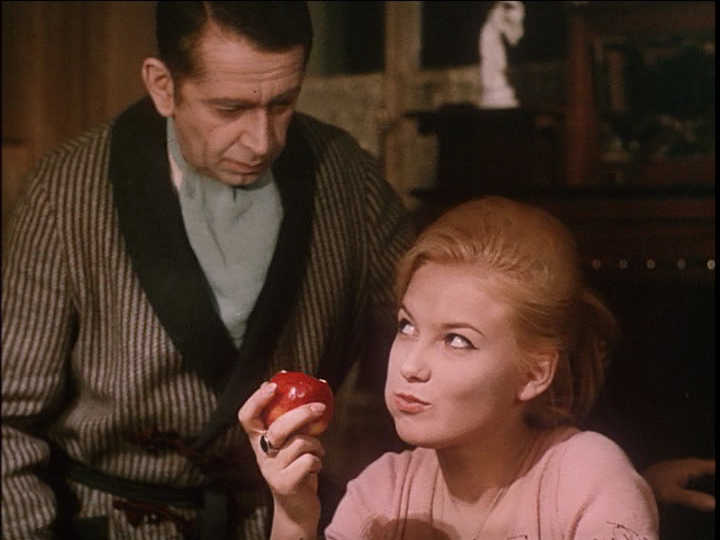

The following evening, it’s Roch’s turn to try his rusty hand at wooing Anna’s charms. Lacking much practice in recent memory, and hardly knowing how to engage her on a relational level, he approaches her with a book, a collection of “chaste love stories,” as he puts it, the title of which translates as The Art of Loving. Just how explicit or erotic the tales ever become, or if the book contains illustrations, we never quite learn, because the poor priest winds up choking on a fish bone that Anna cooked for him, then getting rolled by a bunch of rowdy drunks after they discover their supposedly virtuous canon hanging out with a floozy under cover of darkness.

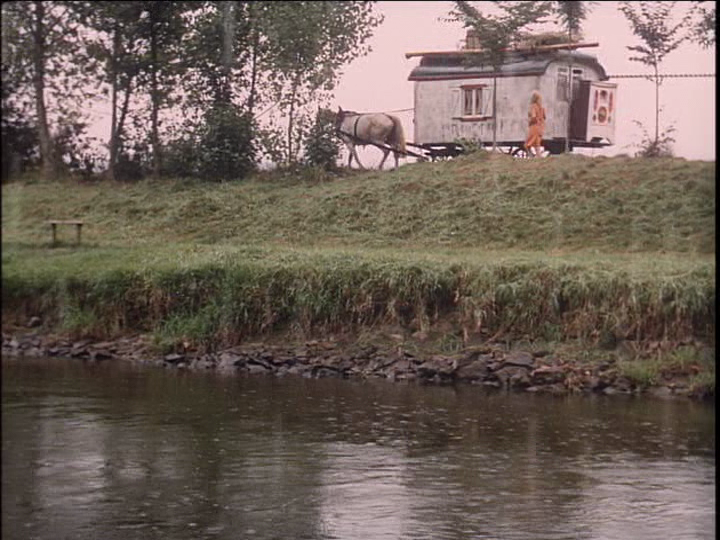

Meanwhile, feeling momentarily estranged from her husband after Antonin’s act of brazen infidelity, Katerina decides to act on her own desires, taking up residence with Ernie in his circus wagon. Quickly assessing the situation, she recognizes Ernie’s need of an experienced hand to keep his place clean and orderly, since Anna’s vanity and laziness obviously places her above performing such mundane tasks. For his part, Ernie seems willing to go along with Katerina’s motherly overtures, for awhile at least. Nothing wrong with having someone do a little tidying up after him, anyway. But when Katerina learns what’s expected of someone living the carnie life, her heart is moved to return to the home where her confused, tormented husband is doubtlessly pining after her in his solitude…

We get no explanation of how Anna wound up traveling with Ernie, whom she describes as “a mediocre magician but a good provider.” Thus, whatever it is that drives Anna, the captivating pivot around whom Capricious Summer‘s action revolves, remains a mystery, as is usually the case with beautiful women. (Actually, I think most humans remain quite mysterious and nearly impossible to adequately explain, the main difference being that most of us are interested in learning all we can only about the people we find highly attractive to begin with.)

Given her occupation and availability, she’s undoubtedly had a lot of experience fending off the advances of suitors much more polished and persuasive than Antonin, Roch and Hugo. Her playful expressions show that she’s having fun with the bumbling gents, and her deft management of each encounter allows her to maintain the upper hand, even when the odds and match-up of physical strengths seem to stack against her. The role is played by Jana Preissova (credited here as Jana Drchalova), who went on to act mainly in Czech TV and a handful of obscure (in the West, anyway) movies. It’s a shame we aren’t likely to see more of her in the world of Criterion-related films.

Even the most genial and pleasant of pastimes must eventually come to an end, and Capricious Summer is commended for not wearing out its welcome. Delivering its punch in a little over an hour, that’s plenty enough time for us to absorb the reminder that it gives about the fitful, delusional effects that Eros can exert over us in moments of complacency or distraction, and once Cupid’s darts have settled in, how their impulsive power can drive us to acts of foolishness that are as humorous as they are ultimately forgivable. Ah, if only the capriciousness of the human heart could be safely confined to one languid season of the year!