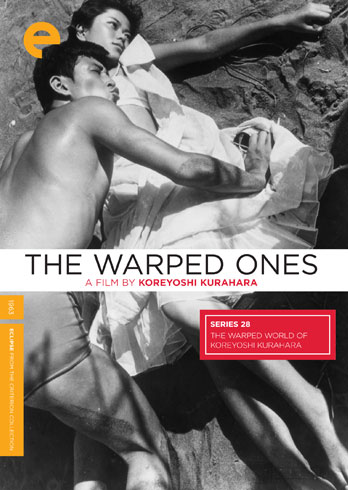

Regular readers of this column know by now that whenever an Eclipse film falls into the chronology I’ve created for my Criterion Reflections blog, I’ll use that as the pretext for selecting it as my next leg on this Journey Through the Eclipse Series. That’s what’s happening this week with The Warped Ones, a 1960 entry from Eclipse Series 28: The Warped World of Koreyoshi Kurahara. It’s the second titles I’ve reviewed from that box, the first being Intimidation, also dating from that same year. While the two bear some trademark stylistic similarities, their topical subjects are quite different: Intimidation is set in the business world, a similar environment to the next film up on my blog, Akira Kurosawa’s The Bad Sleep Well, while The Warped Ones represents Kurahara’s re-entry into the Sun Tribe sub-genre that had exploded into Japanese pop culture in the latter half of the 1950s and was reaching for new heights of scandal and outrage in depicting the wildness and decadence of an emerging generation.

I reviewed Kurahara’s 1957 debut feature, I Am Waiting, last year as part of the Nikkatsu Noir Eclipse set, and while that film had its fair share of frenetic youth-gone-wild moments, if you put it alongside The Warped Ones, it feels like a mere warm-up act in terms of sheer energy and emotional abandon. Watching The Warped Ones‘ frenzied 75-minute dash to oblivion, and its massive popularity in Japan at that time, sure got me thinking, just what was going on in Japan back then to inspire this kind of cinema? Were the kids really this messed up? Was the cultural repression and/or economic inequality so hard as to make such a sociopathic crime spree seem like a reasonable, justifiable response? My curiosity about such questions got the best of me, so I spent time this week seeking out similar material, landing on a pair of films that preceded this one: Nagisa Oshima’s Cruel Story of Youth and The Sun’s Burial. Neither are available on disc from Criterion quite yet, but they can both be accessed through their Hulu Plus channel, which is where I saw them. I can’t take the time to give either of the Oshima films their due consideration here, but they are powerful works that I seriously hope will be issued on disc by Criterion in the very near future. An “Early Oshima” Eclipse set would be great, but why stop there? The Sun’s Burial in particular is a visually gorgeous film that would look great in hi-def. And it has a beautifully contemplative guitar-based soundtrack as well to take advantage of the uncompressed audio capabilities. Watching these three movies in close succession, as I did this weekend, really sets the stage for better understanding the often vicious, unrestrained and restless creativity that came to characterize Japanese cinema in the decade that followed.

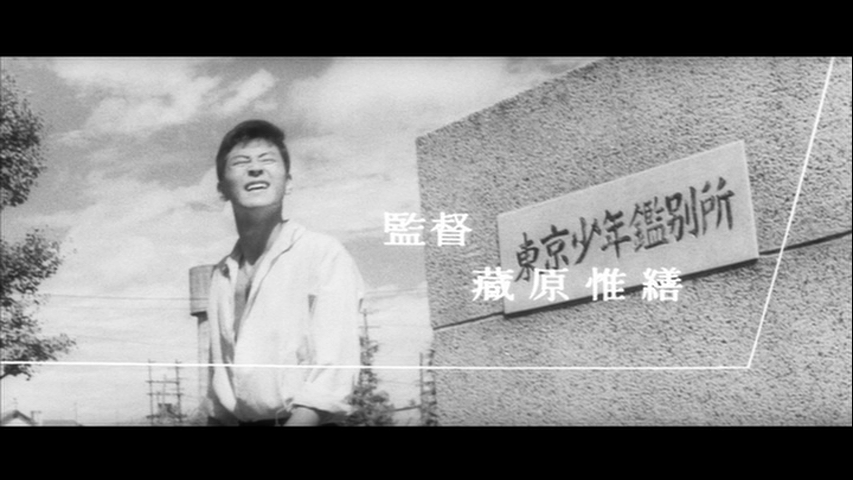

The Warped Ones begins with a little vignette as we see Yuki, a pretty and hysterical young woman, chatting up a white, presumably wealthy patron at a bar. She’s serving as a decoy for her friend Akira, giving him the signal when it’s time for him to move in and pick the gentleman’s pocket. Unbeknownst to them both, they’re being watched by an undercover cop, who’s been tipped off by a beat reporter to keep an eye on those two. When the pilfering turns into an arrest, a brief scuffle breaks out between Akira and the newspaper man, with the news hound getting the worst of the deal as his distraught girlfriend looks on. Akira and Yuki are cuffed and hauled away to juvenile detention, where they receive further education in the art and science of petty crime as the opening credits roll. And with that, The Warped Ones pushes the accelerator to the floor and never lets up.

Immediately upon his release, Akira teams up with Masaru, a new buddy he made while in confinement, ready to pick up right where he left off. An air-raid drill puts him, the citizens of Tokyo and the audience on simultaneous alert for danger, risk, impending catastrophe. Akira and Masaru pay no heed and plunge ahead, acting on impulse and seizing the opportunity to swipe a gleaming Ford Fairlane. Judging from this film, and Breathless, cars sure used to be easy to steal, back in the day.

Something in Akira’s central nervous system seems to work more immediately and efficiently than it does in most of the rest of us. Whatever feelings are stirred up in him in any given moment find quick and even amplified release. He’s constantly grimacing, barking, exclaiming, exulting, or just getting lost in the swirl of emotions that wash over him when his criminal intentions meet with success, he meets up with real or potential rivals or lovers, or hears the wild unpredictable improvisations of bebop jazz. Tamio Kawachi, the actor who plays Akira, delivers an incredibly uninhibited performance, and I’ll be seeing more of him as he makes appearances in several other Eclipse and Criterion films to come, so we’ll find out if he’s able or asked to maintain such a frantic pace.

Within a few minutes of tearing through the city in their stolen vehicle, Akira and Masaru reconnect with Yuki, who’s beyond eager to jump into a new cycle of craziness with her friend. Following this trio, and the chubby pedophile that she drags along for a few minutes in order to eventually rob and set up for arrest, is quite a rush as they launch themselves with nary a forethought of future consequences or complications that might stem from their deeds. On a gut level, films like this serve a social purpose in actualizing some of the suppressed urges we all carry around with us, and some act on. As Akira strips off his shirt prior to hot-wiring the car, as Masaru lunges over the front seat to make his aggressive pass at Yuki and she harshly pushes him away while alluring him with her manic laughter, those of us living more proper and constrained lives get the satisfaction of identification while risking practically nothing. What fun.

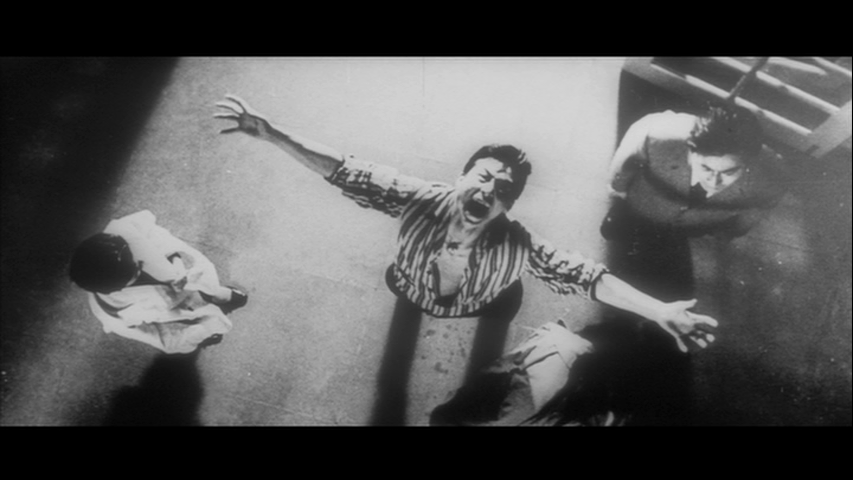

Those who know Kurahara know that he’s very fond of radical vertical camera perspectives, and here’s just one example of that, as he takes Kurosawa’s signature “lens into the sun” move from Rashomon several steps further by repeatedly going there – up, down, sideways, swirling – working his cameraman into the same kind of lathery sweat that we often see on the faces of The Warped Ones themselves.

And the bluntness of Kurahara’s approach doesn’t merely extend into the realm of violence or property crimes – Akira is also a rapist, and as the situation later develops, corrosively indifferent to the fact that his sexual aggression results in a pregnancy. This makes him, by most peoples’ values, a corrupted and detestable character, based on the moral weight of his actions, and yet we are forced to continually identify with him if we choose to stay on board with the film. Is Kurahara guilty of creating a kind of sympathy for the devil? That’s the dilemma that we’re faced with in trying to assess the message or significance of his film. But maybe drawing a lesson from The Warped Ones is the wrong approach.

Much like the world that Oshima sketches for us in Cruel Story of Youth‘s young couple who assault and extort money from horny middle-aged men, or The Sun’s Burial‘s milieu of Lower Depths-scale squalor and nihilistic depravity, The Warped Ones functions as a Beat-era howl of flailing protest – letting the Powers That Be know that a serious problem resides in their midst, unsure of exactly what to do to fix it and not feeling responsible to come up with that solution in any case since the oppressed are not those who created those conditions in the first place. Somewhat similar in fact to what’s happening in today’s Occupy Movement protests, not only on Wall Street but in many cities all around the world.

This video clip gives not only a nice sample of Kurahara’s style but also Akira’s id-unleashed gyrations as he sees a picture advertising the art exhibit of Fumiko, his kidnap/rape victim and now bearer of his child, as he learned in the scene just prior. He marches into this rarefied environment, oblivious to the prescribed patterns of behavior, the proverbial bull in a china shop. Just as telling as his overt mockery and unruliness in that situation is the reluctance of anyone else to step forward and confront Akira or make any effort to put his behavior in check. Instead, they just walk away, mildly offended and slightly uncomfortable, preferring not to make any waves or get personally involved in the life of a guy who seriously needs some help. This point is driven even further in subsequent scenes, as Akira enters into the avant-garde clique as an example of “extraordinary fauvism” to the delight of the high-cultured snobby dilettantes, before he appalls and offends them with further acts of senseless vandalism.

The revelation of further plot details or in-depth analysis of what follow that scene matters less than that a film like The Warped Ones was made, once upon a time, and now fifty years later shrieks back at us from the vaults of history to leave the impression that many many lives have come and gone over those decades with little hope for redemption or even a fair opportunity to make atonement for past grievances. There’s no excusing Akira, Masura, Yuki or even Fumiko for the trespasses they commit on film – they are young, naive, confused and overwhelmed. Weren’t we all, at one time or another? The value resides in capturing these moments, this vortex of adrenalin, desire, appetite and fear, so that at some point further down the line (assuming we survived our run through the gauntlet) we can look back and contemplate the ordeal and, if life allows us that privilege, to steer other young pilgrims through their own passage, avoiding the full-fledged annihilation that accompanies a stretch of life spent as one of The Warped Ones.