With Criterion’s long-awaited addition of India’s Satyajit Ray to their pantheon of all-time great directors about to be made official tomorrow with the release of The Music Room, my thoughts inexorably turned to India as I contemplated my next entry for this column. Given that Louis Malle himself has had two of his films (Zazie dans le Metro and Black Moon) recently published by Criterion, and that Ray was a Bengali who based his films in the northeastern corner of that great subcontinent, it make perfect sense that our Journey through the Eclipse Series takes a passage to India, landing in Calcutta, from Eclipse Series 2: The Documentaries of Louis Malle.

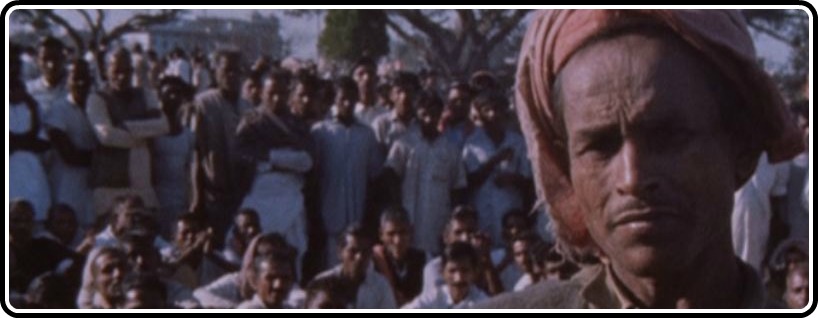

Like the fabled city itself, Malle’s Calcutta is a sprawling, vast, messy and barely fathomable explosion of humanity at its rawest and most visceral, at least to the extent that a documentary film can convey that raw viscerality. Filmed in 1968 and culled out from even more extensive footage that he released in Phantom India, a 7-part TV miniseries also included in this set, Calcutta was deemed capable of standing on its own as a theatrical feature. I agree with the decision – as impressive as Phantom India is (and I’m still scratching my head as to how I will ever manage to summarize and review it here), Calcutta capably stands on its own as an expression of human adaptability and the overpowering drive for survival for its own sake, even in the face of appalling poverty, crippling disease and a profound dearth of resources that might drain the weaker among us of the will to carry on.

India was arguably at its high-water mark of cultural influence in the West when Malle took his epic journey to the East. The Beatles spent a couple months grooving with the Maharishi early in 1968; Hindu motifs had found their way onto album covers for Jimi Hendrix, the Grateful Dead and dozens if not hundreds of other trend-followers; the teachings of Mohandas Ghandi were popularized by social movement leaders like Martin Luther King, Jr. The restless exploratory quests that were sweeping across the USA and Europe found a creative, intriguing alternative in India’s ancient and radically different perspectives on life’s meaning and purpose. So it doesn’t surprise me in the slightest that a sensitive, intuitively perceptive artist like Malle would find value in stepping off the Continent for an extended period of time and see what kind of wisdom could be gleaned from this venerable cradle of civilization.

What Malle found there is amply documented in Calcutta‘s swiftly-flowing 99 minutes. The film opens abruptly with scenes of men taking their ritual ablutions in the industrially-compromised waters of the Hooghly River, but rapidly moves, without narrative guidance, to a broader urban panorama, informing us that we are indeed plunged into the midst of an incomprehensibly dense and busy metropolis. The level of activity is massive, with hordes of people from every imaginable station in life mingling and moving through each other, each individual intent on pursuing their own undeclared agenda, even if it’s nothing more ambitious than sitting in the middle of the road forcing passing vehicles to swerve around them.

The sheer pressure of moving thousands of bodies through their appointed courses weighs heavily as we see scenes of swarming train stations, loads of heavy cargo balanced atop the heads of worn-down laborers, men hanging by a hand from buses or sitting atop train cars, forced to duck low as they pass through tunnels, just to hitch a ride to wherever they’re headed. Cattle freely mingle with pedestrians, haunching down on street corners chewing their cuds alongside beggars, businessmen and naked children. Whatever kind of street environments or sidewalk cultures we may find compelling in our contemporary scenes, it’s a fair bet that Calcutta will blow them away in terms of strangeness and the extremity of human conditions revealed there.

Around the 20 minute mark, we’re given a reprieve from being mere gawkers at a world we can barely begin to comprehend, as Malle’s voice interjects to inform us that India too had its share of political upheaval and unrest of the sort that immediately comes to mind when the year 1968 is mentioned. He covers a protest led by young Communist women, breaking away from that to show the preparations for a traditional religious festival which has to be seen to be believed, even though you won’t understand it. Then, just as we’re tempted to write off India as a thoroughly exotic and incomprehensible enigma, we’re introduced to Calcutta’s affluent bourgeois subculture: men and women of leisure, attending horse races, golfing and generally reaping the economic benefits of decisions made by their ancestors to get on board with the British colonial enterprise several generations ago.

Keeping with the spirit of his times, Malle continues to direct our thoughts toward the economic disparities and injustice that he witnessed in Calcutta (now properly referred to as Kolkata, just as Bombay has been renamed Mumbai.) He fills us in on the city’s history as a colonial outpost, its subsequent abandonment by the British when they relinquished their imperialist ambitions, and how that void has been filled by Pakistani refugees, Chinese immigrants and others. Malle continues to interweave fascinating cross-cultural spectacle with his clear desire to raise our political awareness, not only of what’s happening in India, but in any society where exploitation of the vulnerable and powerless may occur.

As entrancing as Calcutta undoubtedly is to watch in 2011, I found myself strongly desiring some kind of an update, just to see what has changed or what remains the same in this magnificent yet heart-wrenching crucible of humanity. India, of course, is one of the rising superpowers among nations as its economic clout continues to catch up with its abundant population. Ever since I was a child, Calcutta has been synonymous with abject poverty and suffering, an image made concrete by the veneration of Mother Teresa and her Missionaries of Charity over the past few decades. We see a nun from her order (at least, she’s wearing that familiar white head-covering with the blue stripe) in one scene, though Teresa herself is never mentioned.

Though a city of Calcutta’s size and fame obviously has a lot more sustaining it than impoverished beggars and other examples of the lowliest among us, it’s a hard reputation to shake, especially given all the reinforcement of the wretchedness we see in Calcutta’s concluding segment, a visit to a leper colony that is truly as pitiful as anything I’ve ever seen on a movie screen. Even watching documentaries like Renais’ Night and Fog, one can compartmentalize the Holocaust as an atrocity of the worst sort that has, mercifully, concluded and been corrected. Calcutta shows how millions of people go on living in the most abject poverty and suffering… with no end to that problem apparently in sight.

Fairly or not, Malle’s film has taken some flak from those who accuse him of either exploiting the poor people of Calcutta or simply furthering condescending stereotypes that serve to justify a patronizing Orientalist prejudice against the people who live in this part of the world. While there are certainly some worthwhile points of debate regarding the ethics of what we see on screen and how Malle chooses to present it, I think it’s a gross error to accuse him as harshly as the above reviewers do. But that’s just from where I sit, after all! As much as I may disagree with the sentiments expressed in those critical comments, I still have to respect the views of someone who actually lives in India, knows what’s happening in Kolkata nowadays, and harbors some residual resentment of the negative effects that Western interlopers may have had on their beloved homeland.

Still, I think it’s fair to offer up a defense of Malle as a consummate artist who simply captured what happened to be in front of his camera at the time, edited the raw film judiciously, and turned it loose on the world from a perspective that is ultimately compassionate and humane. He’s capturing images and situations that few would ever dare to reveal, and using the prominence of his earlier cinematic triumphs to gain an audience that otherwise might not bother to tune in. Personally, I consider Calcutta to be an heroic achievement – an example of cinema’s power to access layers of consciousness that are otherwise immune to the pleas and appeals of ordinary discourse. Calcutta is a film that needs to be watched multiple times, and grappled with, before it’s set aside. There’s a lot to absorb here, and I’m not done with it yet.